Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński

Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński | |

|---|---|

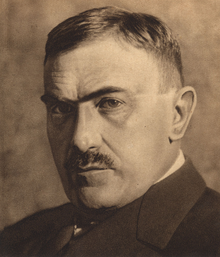

Boy-Żeleński in 1933 | |

| Born | Tadeusz Kamil Marcjan Żeleński 21 December 1874 |

| Died | 4 July 1941 (aged 66) |

| Cause of death | Massacre |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Education | Bartłomiej Nowodworski High School |

| Alma mater | Jagiellonian University |

| Known for | Cabaret Zielony Balonik |

| Signature | |

Tadeusz Kamil Marcjan Żeleński (21 December 1874 – 4 July 1941), better known by his pen name Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński or simply as Boy, was a Polish stage writer, poet, critic and, above all, the translator of over 100 French literary classics into Polish. He was a pediatrician and gynecologist by profession.

A notable personality in the Young Poland movement of c. 1890 to 1918, Boy was the enfant terrible of the Polish literary scene in the first half of the 20th century. He was murdered in July 1941 by invading German forces during what became known as the massacre of the Lwów professors.

Early life

[edit]

Tadeusz Kamil Marcjan Żeleński (of the Ciołek coat-of-arms) was born on 21 December 1874 in Warsaw, to Wanda, née Grabowska, who was from a Frankist family of converts to Catholicism,[1] and Władysław Żeleński, a prominent composer and musician. Tadeusz's cousin was the notable Polish neo-romantic poet Kazimierz Przerwa-Tetmajer. Because higher education in Polish was forbidden in Warsaw under Russian rule, in 1892 Żeleński left for Kraków, in Austrian-ruled Galicia, where he enrolled at the Jagiellonian University medical school.

Completing his studies in 1900, Żeleński began medical practice as a pediatrician. In 1906 he opened a practice as a gynaecologist, which gave him financial freedom. The same year, he co-organised the famous Zielony Balonik ("Green Balloon") cabaret, which gathered notable personalities of Polish culture, including his brother Edward and Jan August Kisielewski, Stanisław Kuczborski, Witold Noskowski, Stanisław Sierosławski, Rudolf Starzewski, Edward Leszczyński, Teofil Trzciński, Karol Frycz, Ludwik Puget, Kazimierz Sichulski, Jan Skotnicki and Feliks Jasieński.

In the sketches, poems, satirical songs, and short stories that he wrote for Zielony Balonik, Boy-Żeleński criticized and mocked the conservative authorities and the two-faced morality of the city folk, but also the grandiloquent style of Młoda Polska and Kraków's bohemians. This earned him a reputation as the "enfant terrible" of Polish literature.

World War I and interbellum

[edit]

At the outbreak of World War I, Żeleński was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian Army and served as medic to railway troops. After the war, he returned to Poland and, in 1922, moved to Warsaw. He did not return to his medical practice but instead focused entirely on writing.

Working for various dailies and magazines, Boy-Żeleński soon became one of the authorities of the Polish liberal and democratic intelligentsia. He criticized the two-faced morality of the clergy, promoted the secularization of public life and culture, and was one of the strongest advocates for the equality of women. He was one of the first public figures in Poland to support a women's right to legal abortion. Also, Boy-Żeleński often fought in his essays against the Polish romantic tradition, which he saw as irrational and as seriously distorting the way Polish society thought about its past.

In addition, Boy translated over 100 classics of French literature, which ever since have been considered among the best translations of foreign literature into Polish. In 1933, Boy-Żeleński was admitted to the prestigious Polish Academy of Literature.

World War II

[edit]

After the outbreak of World War II, Boy-Żeleński moved to Soviet-occupied Lwów, where he stayed with his wife's brother-in-law. Boy joined the Soviet-led University as the head of the Department of French Literature. Criticized by many for his public and frequent collaboration with the Soviet occupation forces, he maintained contacts with many prominent professors and artists, who found themselves in the city after the Polish Defensive War. He also took part in creating the Communist propaganda newspaper Czerwony Sztandar ("Red Banner") and became one of the prominent members of the Society of Polish Writers.

After Nazi Germany broke the German–Soviet treaty and attacked the Soviet Union and the Soviet-held Polish Kresy, Boy remained in Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine). The city was captured on the night of 4 July 1941. He was arrested and taken to the Wulka Hills, where he was murdered. He was falsely accused by Germans for being "a Soviet spy". He was killed together with 45 other Polish professors, artists and intelligentsia in what became known as the massacre of Lwów professors.

See also

[edit]- Polish literature

- List of Poles

- Culture of Kraków

- Zielony Balonik

- Wpływologia

- List of physician writers (20th century)

References

[edit]- ^ Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, Basil Blackwell for the Institute for Polish-Jewish Studies, 1986, p. 190

External links

[edit] Media related to Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński at Wikimedia Commons- Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński at Culture.pl

- Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński at poezja.org

- Works by Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- 1874 births

- Writers from Warsaw

- People from Warsaw Governorate

- Clan of Ciołek

- 20th-century Polish poets

- 20th-century Polish dramatists and playwrights

- Polish translators

- French–Polish translators

- Literary translators

- Polish male poets

- Polish male dramatists and playwrights

- Polish journalists

- Polish pediatricians

- Polish atheists

- Jagiellonian University alumni

- Members of the Polish Academy of Literature

- Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I

- Officers of the Order of Polonia Restituta

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- Officers of the Legion of Honour

- Knights of the Legion of Honour

- Deaths by firearm in Ukraine

- Polish civilians killed in World War II

- Victims of the Massacre of Lwów professors

- Executed people from Masovian Voivodeship

- 20th-century Polish male writers