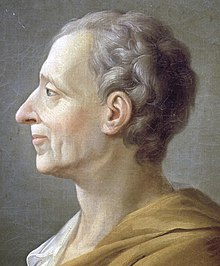

Montesquieu

Montesquieu | |

|---|---|

Portrait by an anonymous artist, c. 1753–1794 | |

| Born | 18 January 1689 Château de la Brède, La Brède, Aquitaine, France |

| Died | 10 February 1755 (aged 66) Paris, France |

| Spouse |

Jeanne de Lartigue (m. 1715) |

| Children | 3 |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Enlightenment Classical liberalism |

Main interests | Political philosophy |

Notable ideas | Separation of state powers: executive, legislative, judicial; classification of systems of government based on their principles |

| Signature | |

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu[a] (18 January 1689 – 10 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal source of the theory of separation of powers, which is implemented in many constitutions throughout the world. He is also known for doing more than any other author to secure the place of the word despotism in the political lexicon.[3] His anonymously published The Spirit of Law (1748), which was received well in both Great Britain and the American colonies, influenced the Founding Fathers of the United States in drafting the U.S. Constitution.

Biography

Montesquieu was born at the Château de la Brède in southwest France, 25 kilometres (16 mi) south of Bordeaux.[4] His father, Jacques de Secondat (1654–1713), was a soldier with a long noble ancestry, including descent from Richard de la Pole, Yorkist claimant to the English crown. His mother, Marie Françoise de Pesnel (1665–1696), who died when Charles was seven, was an heiress who brought the title of Barony of La Brède to the Secondat family.[5] His family was of Huguenot origin.[6][7] After the death of his mother he was sent to the Catholic College of Juilly, a prominent school for the children of French nobility, where he remained from 1700 to 1711.[8] His father died in 1713 and he became a ward of his uncle, the Baron de Montesquieu.[9] He became a counselor of the Bordeaux Parlement in 1714. He showed preference for Protestantism[10][11] and in 1715 he married the Protestant Jeanne de Lartigue, who eventually bore him three children.[12] The Baron died in 1716, leaving him his fortune as well as his title, and the office of président à mortier in the Bordeaux Parlement,[13] a post that he would hold for twelve years.

Montesquieu's early life was a time of significant governmental change. England had declared itself a constitutional monarchy in the wake of its Glorious Revolution (1688–1689), and joined with Scotland in the Union of 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. In France, the long-reigning Louis XIV died in 1715 and was succeeded by the five-year-old Louis XV. These national transformations had a great impact on Montesquieu; he would refer to them repeatedly in his work.

Montesquieu eventually withdrew from the practice of law to devote himself to study and writing. He achieved literary success with the publication of his 1721 Persian Letters (French: Lettres persanes), a satire representing society as seen through the eyes of two Persian visitors to Paris, cleverly criticizing absurdities of contemporary French society. The work was an instant classic and accordingly was immediately pirated. In 1722, he went to Paris and entered social circles with the help of friends including the Duke of Berwick whom he had known when Berwick was military governor at Bordeaux. He also acquainted himself with the English politician Viscount Bolingbroke, some of whose political views were later reflected in Montesquieu's analysis of the English constitution. In 1726 he sold his office, bored with the parlement and turning more toward Paris. In time, despite some impediments he was elected to the Académie Française in January 1728.

In April 1728, with Berwick's nephew Lord Waldegrave as his traveling companion, Montesquieu embarked on a grand tour of Europe, during which he kept a journal. His travels included Austria and Hungary and a year in Italy. He went to England at the end of October 1729, in the company of Lord Chesterfield, where he was initiated into Freemasonry at the Horn Tavern Lodge in Westminster.[14] He remained in England until the spring of 1731, when he returned to La Brède. Outwardly he seemed to be settling down as a squire: he altered his park in the English fashion, made inquiries into his own genealogy, and asserted his seignorial rights. But he was continuously at work in his study, and his reflections on geography, laws and customs during his travels became the primary sources for his major works on political philosophy at this time.[15] He next published Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline (1734), among his three best known books. He was to publish The Spirit of Law in 1748, quickly translated into English. It quickly rose to influence political thought profoundly in Europe and America. In France, the book met with an enthusiastic reception by many but was denounced by the Sorbonne and, in 1751, by the Catholic Church (Index of Prohibited Books). It received the highest praise from much of the rest of Europe, especially Britain.

Montesquieu was also highly regarded in the British colonies in North America as a champion of liberty. According to a survey of late eighteenth-century works by political scientist Donald Lutz, Montesquieu was the most frequently quoted authority on government and politics in colonial pre-revolutionary British America, cited more by the American founders than any source except for the Bible.[16] Following the American Revolution, his work remained a powerful influence on many of the American founders, most notably James Madison of Virginia, the "Father of the Constitution". Montesquieu's philosophy that "government should be set up so that no man need be afraid of another"[17] reminded Madison and others that a free and stable foundation for their new national government required a clearly defined and balanced separation of powers.

Montesquieu was troubled by a cataract and feared going blind. At the end of 1754 he visited Paris and was soon taken ill, and died from a fever on 10 February 1755. He was buried in the Église Saint-Sulpice, Paris.

Philosophy of history

Montesquieu's philosophy of history minimized the role of individual persons and events. He expounded the view in Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, that each historical event was driven by a principal movement:

It is not chance that rules the world. Ask the Romans, who had a continuous sequence of successes when they were guided by a certain plan, and an uninterrupted sequence of reverses when they followed another. There are general causes, moral and physical, which act in every monarchy, elevating it, maintaining it, or hurling it to the ground. All accidents are controlled by these causes. And if the chance of one battle—that is, a particular cause—has brought a state to ruin, some general cause made it necessary for that state to perish from a single battle. In a word, the main trend draws with it all particular accidents.[18]

In discussing the transition from the Republic to the Empire, he suggested that if Caesar and Pompey had not worked to usurp the government of the Republic, other men would have risen in their place. The cause was not the ambition of Caesar or Pompey, but the ambition of man.

Political views

| Part of the Politics series |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in France |

|---|

|

Montesquieu is credited as being among the progenitors, who include Herodotus and Tacitus, of anthropology—as being among the first to extend comparative methods of classification to the political forms in human societies. Indeed, the French political anthropologist Georges Balandier considered Montesquieu to be "the initiator of a scientific enterprise that for a time performed the role of cultural and social anthropology".[19] According to social anthropologist D. F. Pocock, Montesquieu's The Spirit of Law was "the first consistent attempt to survey the varieties of human society, to classify and compare them and, within society, to study the inter-functioning of institutions."[20] "Émile Durkheim," notes David W. Carrithers, "even went so far as to suggest that it was precisely this realization of the interrelatedness of social phenomena that brought social science into being."[21] Montesquieu's political anthropology gave rise to his influential view that forms of government are supported by governing principles: virtue for republics, honor for monarchies, and fear for despotisms. American founders studied Montesquieu's views on how the English achieved liberty by separating executive, legislative, and judicial powers, and when Catherine the Great wrote her Nakaz (Instruction) for the Legislative Assembly she had created to clarify the existing Russian law code, she avowed borrowing heavily from Montesquieu's Spirit of Law, although she discarded or altered portions that did not support Russia's absolutist bureaucratic monarchy.[22]

Montesquieu's most influential work divided French society into three classes (or trias politica, a term he coined): the monarchy, the aristocracy, and the commons.[clarification needed] Montesquieu saw two types of governmental power existing: the sovereign and the administrative. The administrative powers were the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. These should be separate from and dependent upon each other so that the influence of any one power would not be able to exceed that of the other two, either singly or in combination. This was a radical idea because it does not follow the three Estates structure of the French Monarchy: the clergy, the aristocracy, and the people at large represented by the Estates-General, thereby erasing the last vestige of a feudalistic structure.

The theory of the separation of powers largely derives from The Spirit of Law:

In every state there are three kinds of power: the legislative authority, the executive authority for things that stem from the law of nations, and the executive authority for those that stem from civil law.

By virtue of the first, the prince or magistrate enacts temporary or perpetual laws, and amends or abrogates those that have been already enacted. By the second, he makes peace or war, sends or receives embassies, establishes the public security, and provides against invasions. By the third, he punishes criminals, or determines the disputes that arise between individuals. The latter we shall call the judiciary power, and the other, simply, the executive power of the state.

— The Spirit of Law, XI, 6.

Montesquieu argues that each power should only exercise its own functions; he is quite explicit here:

When in the same person or in the same body of magistracy the legislative authority is combined with the executive authority, there is no freedom, because one can fear lest the same monarch or the same senate make tyrannical laws in order to carry them out tyrannically. Again there is no freedom if the authority to judge is not separated from the legislative and executive authorities. If it were combined with the legislative authority, power over the life and liberty of the citizens would be arbitrary, for the judge would be the legislator. If it were combined with the executive authority, the judge could have the strength of an oppressor. All would be lost if the same man or the same body of principals, or of nobles, or of the people, exercised these three powers: that of making laws, that of executing public resolutions, and that of judging crimes or disputes between individuals.

— The Spirit of Law, XI, 6.

If the legislative branch appoints the executive and judicial powers, as Montesquieu indicated, there will be no separation or division of its powers, since the power to appoint carries with it the power to revoke.

The executive authority must be in the hands of a monarch, for this part of the government, which almost always requires immediate action, is better administrated by one than by several, whereas that which depends on the legislative authority is often better organized by several than by one person alone.

If there were no monarch, and the executive authority were entrusted to a certain number of persons chosen from the legislative body, that would be the end of freedom, because the two authorities would be combined, the same persons sometimes having, and always in a position to have, a role in both.

— The Spirit of Law, XI, 6.

Montesquieu identifies three main forms of government, each supported by a social "principle": monarchies (free governments headed by a hereditary figure, e.g. king, queen, emperor), which rely on the principle of honor; republics (free governments headed by popularly elected leaders), which rely on the principle of virtue; and despotisms (unfree), headed by despots which rely on fear. The free governments are dependent on constitutional arrangements that establish checks and balances. Montesquieu devotes one chapter of The Spirit of Law to a discussion of how the England's constitution sustained liberty (XI, 6), and another to the realities of English politics (XIX, 27). As for France, the intermediate powers (including the nobility) the nobility and the parlements had been weakened by Louis XIV, and welcomed the strengthening of parlementary power in 1715.

Montesquieu advocated reform of slavery in The Spirit of Law, specifically arguing that slavery was inherently wrong because all humans are born equal,[23] but that it could perhaps be justified within the context of climates with intense heat, wherein laborers would feel less inclined to work voluntarily.[23] As part of his advocacy he presented a satirical hypothetical list of arguments for slavery. In the hypothetical list, he'd ironically list pro-slavery arguments without further comment, including an argument stating that sugar would become too expensive without the free labor of slaves.[23]

While addressing French readers of his General Theory, John Maynard Keynes described Montesquieu as "the real French equivalent of Adam Smith, the greatest of your economists, head and shoulders above the physiocrats in penetration, clear-headedness and good sense (which are the qualities an economist should have)."[24]

Meteorological climate theory

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

Another example of Montesquieu's anthropological thinking, outlined in The Spirit of Law and hinted at in Persian Letters, is his meteorological climate theory, which holds that climate may substantially influence the nature of man and his society, a theory also promoted by the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon. By placing an emphasis on environmental influences as a material condition of life, Montesquieu prefigured modern anthropology's concern with the impact of material conditions, such as available energy sources, organized production systems, and technologies, on the growth of complex socio-cultural systems.

He goes so far as to assert that certain climates are more favorable than others, the temperate climate of France being ideal. His view is that people living in very warm countries are "too hot-tempered", while those in northern countries are "icy" or "stiff". The climate of middle Europe is therefore optimal. On this point, Montesquieu may well have been influenced by a similar pronouncement in The Histories of Herodotus, where he makes a distinction between the "ideal" temperate climate of Greece as opposed to the overly cold climate of Scythia and the overly warm climate of Egypt. This was a common belief at the time, and can also be found within the medical writings of Herodotus' times, including the "On Airs, Waters, Places" of the Hippocratic corpus. One can find a similar statement in Germania by Tacitus, one of Montesquieu's favorite authors.

Philip M. Parker, in his book Physioeconomics (MIT Press, 2000), endorses Montesquieu's theory and argues that much of the economic variation between countries is explained by the physiological effect of different climates.

From a sociological perspective, Louis Althusser, in his analysis of Montesquieu's revolution in method,[25] alluded to the seminal character of anthropology's inclusion of material factors, such as climate, in the explanation of social dynamics and political forms. Examples of certain climatic and geographical factors giving rise to increasingly complex social systems include those that were conducive to the rise of agriculture and the domestication of wild plants and animals.

Memorialization

Between 1981 and 1994, a depiction of Monetesquieu appeared on the 200 French franc note.[26]

Since 1989, the annual Montesquieu prize has been awarded by the French Association of Historians of Political Ideas for the best French-language thesis on the history of political thought.[27]

On Europe Day 2007, the Montesquieu Institute opened in The Hague, the Netherlands, with a mission to advance research and education on the parliamentary history and political culture of the European Union and its member states.[28]

The Montesquieu tower in Luxembourg was completed in 2008 as an addition to the headquarters of the Court of Justice of the European Union.[29] The building houses many of the institution's translation services. Until 2019, it stood, with its sister tower, Comenius, as the tallest building in the country.[29]

List of principal works

- Memoirs and discourses at the Academy of Bordeaux (1718–1721): including discourses on echoes, on the renal glands, on weight of bodies, on transparency of bodies and on natural history, collected with introductions and critical apparatus in volumes 8 and 9 of Œuvres complètes, Oxford and Naples, 2003–2006.

- Spicilège (Gleanings, 1715 onward)

- Lettres persanes (Persian Letters, 1721)

- Le Temple de Gnide (The Temple of Gnidos, a prose poem; 1725)

- Histoire véritable (True History, an "Oriental" tale; c. 1723–c. 1738)

- Considérations sur les causes de la grandeur des Romains et de leur décadence (Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, 1734) at Gallica

- Arsace et Isménie (Arsace and Isménie, a novel; 1742)

- De l'esprit des lois ((On) The Spirit of Law, 1748) (volume 1 and volume 2 from Gallica)

- Défense de "L'Esprit des lois" (Defense of "The Spirit of Law", 1750)

- Essai sur le goût (Essay on Taste, published posthumously in 1757)

- Mes Pensées (My Thoughts, 1720–1755)

A critical edition of Montesquieu's works is being published by the Société Montesquieu. It is planned to total 22 volumes, of which (as of February 2022) all but five have appeared.[30]

See also

- Environmental determinism

- Liberalism

- List of abolitionist forerunners

- List of political systems in France

- List of liberal theorists

- Napoleon

- Politics of France

- Jean-Baptiste de Secondat (1716–1796), his son

- U.S. Constitution, influences

- Bibliography of the United States Constitution — Contains numerous works regarding Montesqui's influence on American constitutionalism.

Notes

References

- ^ "Montesquieu" Archived 21 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Boesche 1990, p. 1.

- ^ "Bordeaux · France". Bordeaux · France.

- ^ Sorel, A. Montesquieu. London, George Routledge & Sons, 1887 (Ulan Press reprint, 2011), p. 10. ASIN B00A5TMPHC

- ^ Enlightenment Contested: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man 1670-1752. OUP Oxford. 12 October 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-927922-7.

- ^ Agreeable Connexions: Scottish Enlightenment Links with France. Casemate Publishers. 5 November 2012. ISBN 9781907909085.

- ^ Sorel (1887), p. 11.

- ^ Sorel (1887), p. 12.

- ^ Montesquieu's Liberalism and the Problem of Universal Politics. Cambridge University Press. 23 August 2018. ISBN 9781108552691.

- ^ Civil Religion: A Dialogue in the History of Political Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. 25 October 2010. ISBN 9781139492614.

- ^ Sorel (1887), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Sorel (1887), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Berman 2012, p. 150

- ^ Li, Hansong (25 September 2018). "The space of the sea in Montesquieu's political thought". Global Intellectual History. 6 (4): 421–442. doi:10.1080/23801883.2018.1527184. S2CID 158285235.

- ^ Lutz 1984.

- ^ Montesquieu, The Spirit of Law, Book 11, Chapter 6, "On the English Constitution." Archived 28 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library, Retrieved 1 August 2012

- ^ Montesquieu (1734), Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, The Free Press, archived from the original on 6 August 2010, retrieved 30 November 2011 Ch. XVIII.

- ^ Balandier 1970, p. 3.

- ^ Pocock 1961, p. 9.

Tomaselli 2006, p. 9, similarly describes it as "among the most intellectually challenging and inspired contributions to political theory in the eighteenth century. [... It] set the tone and form of modern social and political thought." - ^ Carrithers, 1977, p. 27, citing Durkheim 1960, pp. 56–57)

- ^ Ransel 1975, p. 179.

- ^ a b c Mander, Jenny. 2019. "Colonialism and Slavery". p. 273 in The Cambridge History of French Thought, edited by M. Moriarty and J. Jennings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ See the preface Archived 10 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine to the French edition of Keynes' General Theory.

See also Devletoglou 1963. - ^ Althusser 1972.

- ^ "200 Francs Montesquieu | Grand choix de billets de collection de la BDF". Bourse du collectionneur (in French). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Prix Montesquieu - Association Française des Historiens des idées politiques". univ-droit.fr : Portail Universitaire du droit (in French). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Start Montesquieu Instituut". www.montesquieu-instituut.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ a b "Montesquieu Tower". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ^ "Œuvres complètes". Institut d'histoire des représentations et des idées dans les modernités. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

Sources

Articles and chapters

- Boesche, Roger (1990). "Fearing Monarchs and Merchants: Montesquieu's Two Theories of Despotism". The Western Political Quarterly. 43 (4): 741–761. doi:10.1177/106591299004300405. JSTOR 448734. S2CID 154059320.

- Devletoglou, Nicos E. (1963). "Montesquieu and the Wealth of Nations". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. 29 (1): 1–25. doi:10.2307/139366. JSTOR 139366.

- Kuznicki, Jason (2008). "Montesquieu, Charles de Second de (1689–1755)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). Knight, Frank H. (1885–1972). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 341–342. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n164. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Lutz, Donald S. (1984). "The Relative Influence of European Writers on Late Eighteenth-Century American Political Thought". American Political Science Review. 78 (1): 189–197. doi:10.2307/1961257. JSTOR 1961257. S2CID 145253561.

- Tomaselli, Sylvana. "The spirit of nations". In Mark Goldie and Robert Wokler, eds., The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). pp. 9–39.

Books

- Althusser, Louis, Politics and History: Montesquieu, Rousseau, Marx (London and New York: New Left Books, 1972).

- Balandier, Georges, Political Anthropology (London: Allen Lane, 1970).

- Berman, Ric (2012), The Foundations of Modern Freemasonry: The Grand Architects – Political Change and the Scientific Enlightenment, 1714–1740 (Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2012).

- Pocock, D. F., Social Anthropology (London and New York: Sheed and Ward, 1961).

- Ransel, David L., The Politics of Catherinian Russia: The Panin Party (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1975).

- Shackleton, Robert, Montesquieu: a Critical Biography (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961).

- Shklar, Judith, Montesquieu (Oxford Past Masters series). (Oxford and New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- Spurlin, Paul M., Montesquieu in America, 1760–1801 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1941; reprint, New York: Octagon Books, 1961).

- Volpilhac-Auger, Catherine, Montesquieu (Folio Bibliographies) (Paris: Gallimard, 2017). Montesquieu: Let there be Enlightenment, English translation by Philip Stewart, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

External links

- Société Montesquieu, [1]

- A Montesquieu Dictionary, on line: "[2] Archived 27 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine"

- Ilbert, Courtenay (1913). "Montesquieu". In Macdonell, John; Manson, Edward William Donoghue (eds.). Great Jurists of the World. London: John Murray. pp. 1–16. Retrieved 14 February 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Works by Montesquieu at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Montesquieu at the Internet Archive

- Works by Montesquieu at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Free full-text works online

- The Spirit of Laws (Volume 1) Audio book of Thomas Nugent translation

- [3] Archived 27 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine The Spirit of Law, trans. Philip Stewart, open access.

- [4] Archived 13 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine Persian Letters, trans. Philip Stewart, open access.

- Complete ebooks collection of Montesquieu in French.

- Lettres persanes at athena.unige.ch (in French)

- Montesquieu, "Notes on England"

- Montesquieu in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Montesquieu", Institut d'histoire des représentations et des idées dans les modernités (in French)

- Montesquieu

- 1689 births

- 1755 deaths

- 18th-century French novelists

- 18th-century French male writers

- 18th-century French philosophers

- French barons

- Contributors to the Encyclopédie (1751–1772)

- Enlightenment philosophers

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- French Freemasons

- French male novelists

- French monarchists

- French political writers

- French Roman Catholics

- Liberalism in France

- Members of the Académie Française

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- People from Gironde

- French philosophers of history

- Philosophers of law

- French political philosophers