Siphnian Treasury

| Siphnian Treasury | |

|---|---|

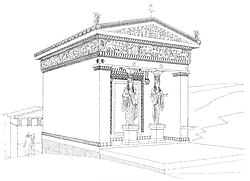

Reconstruction of the Siphnian Treasury by Theophil Hansen | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Treasury |

| Architectural style | Ionic |

| Location | Delphi, Greece |

| Owner | Delphi Archaeological Museum |

The Siphnian Treasury was a building at the Ancient Greek cult centre of Delphi, erected to host the offerings of the polis, or city-state, of Siphnos. It was one of a number of treasuries lining the "Sacred Way", the processional route through the Sanctuary of Apollo, erected to win the favor of the gods and increase the prestige of the donor polis. It was one of the earlier surviving buildings of this type, and its date remains a matter for debate, with the most plausible date being around 525 BC.[1] Until recently it was often confused or conflated with the neighbouring Cnidian Treasury, a similar but less elaborate building, as the remains of the two had become mixed together and earlier theoretical reconstructions used parts of both.[2]

The people of Siphnos had gained enormous wealth from their silver and gold mines in the Archaic period (Herodotus III.57) and used the tithe of their income to erect the treasury, the first religious structure made entirely out of marble. The building was used to house many lavish votive offerings given to the priests to be offered to Apollo.

The Treasury fell to ruins over the centuries, although it stood for much longer than many other monuments, probably due to its decoration which was venerated by the following generations. Currently, the sculpture and a reconstruction of the Treasury are to be seen in the Delphi Archaeological Museum.

Dating of founding

[edit]The only classical source to provide information on this building is Herodotus (3:57-8). If Herodotus is to be deemed a reliable source, this would be sufficient for verifying the date. In his account, Herodotus states that the Siphnians had recently founded a temple at Delphi when a group of Samians arrived asking for support against the tyrannical Polycrates. In respect to this, both Herodotus and Thucydides state that Polykrates ruled during the reign of the Persian king Kambyses (c. 529–522 BC).[3] This would thus date the monument at about 525 BC.[4] one source considers the date of construction as more likely some time absolutely limited to after 480 BC (Whitley).[5]

Description

[edit]

The plan of the treasury has two parts; a pronaos, or porch, and a cella, or enclosure. The pronaos is distyle in antis, i.e., the side walls (Latin antae) extend to the front of the porch, and the pediment is supported by two caryatids instead of plain columns. Below the pediment runs a continuous frieze. The building is 8.27 metres long and 6.09 wide.[6][7][8]

The pediment of the treasury shows the story of Heracles stealing Apollo's tripod, which was strongly associated with his oracular inspiration. The treasury was also one of the first Greek buildings to utilize falling and reclining figures to fill the corners of the pediment. The sculptural friezes that run around the building depict various scenes from Greek mythology. The names of the acting persons were inscribed on the background, most of them are still visible in raking light.[9]

The Eastern side depicts an assembly of the Twelve Olympians seated. In the lost centre of the assembly, Hermes holding the scales filled with the souls of Achilles and Memnon was depicted weighing the souls (psychostasia). To the left are seated the gods protecting Memnon and the Trojans: Apollo, Ares, Aphrodite, and Artemis. In the middle sits Zeus on his throne. On the other half of this frieze one discerns Achilles and Memnon fighting over the body of dead Antilochus. The West side may show the story of the Judgment of Paris, death of Orion or rather Athena translating Heracles to the ME.[10] The north side displays the Gigantomachy. The southern frieze is the most worn out; one discerns clearly the traces of beautifully carved horses; it has been suggested that the scene depicts the abduction of Hippodameia by Pelops or of the Leucippides by the Dioscuri or the abduction of Persephone by Hades. The reliefs were painted over with vivid shades of green, blue, red and gold, thus creating a unique sense of polychromy.

The façade

[edit]On the façade of the Ionic Treasury of the Siphnians there are two korai (maidens) between the pilasters, instead of columns, to support the architrave. This type of opulent decoration featuring female figures full of motion and plasticity foreshadows the Caryatids erected subsequently at the Erechtheion on the Acropolis of Athens.

The east pediment

[edit]

The east pediment is the only surviving pediment of the Siphnian Treasury and depicts a famous Delphic theme. In the center of the pediment there is Zeus (other sources claim it is Athena or Hermes), on the left Apollo and on the right Heracles. The two young gods are competing for the Delphic tripod, and Zeus in the middle is trying to separate them. The sculpture shows the anger of Heracles because Pythia refused to give him an oracle, since he had not been cleansed from the murder of Iphitus. An outraged Heracles has already managed to seize the sacred tripod, and Apollo is trying to pull it away from him.

The east frieze

[edit]

The east frieze depicts a scene from the Assembly of the Gods during the Trojan War, where the gods are discussing the issue with lively gestures like they are arguing. To the right, we see Athena as the head of the gods who side with the Greeks. On the left, we see the gods who protect and defend the Trojans: Apollo, Ares, Aphrodite and Artemis. In the middle, we see Zeus in a lavish throne.

At another part of the frieze, we see a scene from the Trojan war: the scene is a duel over the dead body of a warrior, where the two adversaries are flanked by the heroes of the Achaeans on the right and those of the Trojans respectively on the left. The figure of old Nestor is encouraging the Greeks.

The north frieze

[edit]

The theme on the north frieze is the Battle of the Giants (Gigantomachy), namely the battle of the sons of the Earth, the Giants, with the Olympian gods for power. It is a widespread myth about the conflict between the old and the new world order, depicted very frequently in ancient Greek art. It symbolizes the triumph of order and civilization over savagery, barbarism and anarchy. On one side are the Giants. Heavily armed with helmets, shields, breastplates and greaves, they are attacking the gods from the right with spears, swords and stones. On the opposite side are the gods. First, Hephaestus stands out with his short chiton, standing in front of his bellows. He is followed by two females fighting two Giants, then Dionysus (or possibly Heracles), and Themis on her chariot drawn by lions. A pair of gods who are shooting their arrows against the Giants must be Artemis and Apollo. They are followed by the other gods, but these sculptures do not survive in good condition.

This side of the frieze could be seen from the Sacred Way, as the pilgrims ascended towards the Oracle. This way, they had the opportunity to admire the scene of Gigantomachy, which transforms through the artistic relief into a narrative, unfolding in multiple levels, which nevertheless maintains its visibility, consistency and figurative nature despite the interwoven figures and the various action scenes.

The west frieze

[edit]Unfortunately, only a few relief figures have survived on the west frieze. The theme portrayed here is traditionally thought to be the Judgment of Paris, where the most beautiful goddess would be selected from among Aphrodite, Hera, and Athena. The first goddess coming to be judged is Athena, standing proud on the winged chariot with Hermes as her charioteer. Elsewhere, we see Aphrodite descending from her chariot, with a particular grace, holding the strings of what some interpret to be a necklace. In the section of the frieze that has been lost, one could imagine Hera mounting her chariot angrily to depart after her rejection.

This interpretation has come under scrutiny, however. Neer writes that the Judgement narrative has been somewhat forced upon this frieze, spending too much time on glaring blanks and not enough analyzing what little evidence is present.[11] A major issue lies in the identity of the goddess traditionally thought to be Aphrodite. Although some Hellenistic bronzes do depict Aphrodite with a necklace, there are no examples of this in Archaic art, suggesting that it is something else being held. Neer proposes that these lines are not a necklace, but instead the drawn string of a bow. This interpretation suggests that the figure in question is actually Artemis, changing the narrative of the frieze entirely. This identification is solidified by the fact that Siphnians worshiped Artemis "Of the Disembarkation."[11] Going along with this assertion, one can assume that the missing figure is not Hera, but instead a victim of Artemis' wrath. Though little can confirm this figure's identity, there is a significant hint: palm trees are visible behind Artemis' horses, which is a common Attic painting device to indicate a desolate place. Palm trees are especially connected to the island of Delos, as it was beneath a palm tree on this island that Artemis and Apollo were born. According to Homeric myth, Artemis killed only one person on Delos: Orion. Though this identification cannot be proven outright, it at least accounts for the palm trees, the unusual necklace, and the way that the goddesses appear to be leaving, an extremely uncommon posture in depictions of the Judgement of Paris.

The south frieze

[edit]

Significant portions of the south frieze are missing, so we can only imagine the theme it portrayed. It is probably the also popular theme of abducting women. However, the surviving fragments are the relief, well-sculpted horses portrayed full of energy, which prove the mastery of the artist. As for the craftsmen who worked on the frieze, the opinions of researchers and scholars who studied it are conflicting. Initially, it was believed that it was the work of two different artistic workshops. Gradually, however, this view has been abandoned. It is most likely that there were two main sculptors, around whom two groups of craftsmen worked together. The artist of the north and east sides of the frieze seems more progressive, with his depictions being more active, imaginative and vibrant. In contrast, the artist of south and west side of the frieze insisted on more conservative options, without the bold inspiration and craftsmanship of the first, but with a strong painter-like character and an ionic 'color'.[12][13][14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bommelaer, J.-F., Laroche, D., Guide de Delphes: le Site, Paris 1991

- ^ Dinsmoor, William Bell; Anderson, William James (1973). The Architecture of Ancient Greece: An Account of Its Historic Development. ISBN 9780819602831.

- ^ JM Hall - Artifact and Artifice: Classical Archaeology and the Ancient Historian (p.48) University of Chicago Press, 10 Jan 2014 ISBN 022608096X [Retrieved 2015-3-19]

- ^ J K Darling -Architecture of Greece Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004 ISBN 0313321523 Retrieved 2012-06-16

- ^ J Whitley – The Archaeology of Ancient Greece Cambridge University Press, 4 Oct 2001 ISBN 0521627338 Retrieved 2012-06-25

- ^ J K Darling – Retrieved 2012-06-16

- ^ University of North Carolina – Length Converter Archived 2012-11-05 at the Wayback Machine – Retrieved 2012-06-16

- ^ University of Oxford Classical Art Research Centre & The Beazley Archive Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine showing reconstructed drawing – Retrieved 2012-06-16

- ^ Brinkmann, Vinzenz (1985). "Die aufgemalten Namensbeischriften an Nord- und Ostfries des Siphnierschatzhauses". Bulletin de correspondance hellénique. 109 (1): 77–130. doi:10.3406/bch.1985.1819. ISSN 0007-4217.

- ^ Brinkmann, Vinzenz. (1994). Beobachtungen zum formalen Aufbau und zum Sinngehalt der Friese des Siphnierschatzhauses. Biering & Brinkmann. ISBN 3930609002. OCLC 995118886.

- ^ a b Neer, Richard T. (2001). "Framing the Gift: The Politics of the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi". Classical Antiquity. 20 (2): 273–344. doi:10.1525/ca.2001.20.2.273. JSTOR 10.1525/ca.2001.20.2.273.

- ^ "Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού και Αθλητισμού | Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Δελφών". odysseus.culture.gr (in Greek). Retrieved Dec 22, 2022.

- ^ Βαγγέλη Πεντάζου - Μαρίας Σαρλά, Δελφοί, Β. Γιαννίκος - Β. Καλδής Ο.Ε., 1984, 42.

- ^ Ροζίνα Κολώνια, Το Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Δελφών, Αθήνα, Υπουργείου Πολιτισμού – Ταμείο Αρχαιολογικών Πόρων και Απαλλοτριώσεων, 2009, 29 – 35.

Bibliography

[edit]- Daux, Georges; Hansen, Erik (1987). Le trésor de Siphnos: Fouilles de Delphes. Tome 2 , Topographie et architecture. Paris: De Boccard. p. 471.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Treasury of the Siphnians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Treasury of the Siphnians at Wikimedia Commons

- Michael Scott. Delphi: The Bellybutton of the Ancient World. BBC 4. 26:06 minutes in. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- The Siphnian Treasury: The North side of the frieze (The Gigantomachy - Hall V)

- Hendrix, Andrea. "Siphnian Treasury". Coastal Carolina University. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- "Siphnian Treasury, Delphi Museum". Ancient Greece.org. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- Delphi, Siphnian Treasury Frieze--East (Sculpture) on the Perseus Project