James Farley

James Farley | |

|---|---|

| |

| 50th United States Postmaster General | |

| In office March 4, 1933 – September 10, 1940 | |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Walter Folger Brown |

| Succeeded by | Frank C. Walker |

| Chair of the Democratic National Committee | |

| In office July 2, 1932 – August 17, 1940 | |

| Preceded by | John J. Raskob |

| Succeeded by | Edward J. Flynn |

| Chair of the New York Democratic Party | |

| In office October 1930 – June 1944 | |

| Preceded by | M. William Bray |

| Succeeded by | Paul Fitzpatrick |

| Member of the New York Assembly from Rockland County | |

| In office January 1, 1923 – December 31, 1923 | |

| Preceded by | Pierre DePew |

| Succeeded by | Walter Gedney |

| Personal details | |

| Born | James Aloysius Farley May 30, 1888 Grassy Point, New York, U.S. |

| Died | June 9, 1976 (aged 88) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Gate of Heaven Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Finnegan

(m. 1920; died 1955) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Packard Business College |

James Aloysius Farley (May 30, 1888 – June 9, 1976) was an American politician who simultaneously served as chairman of the New York State Democratic Committee, chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and Postmaster General under President Franklin Roosevelt, whose gubernatorial and presidential campaigns were run by Farley.

Farley was commonly referred to as a political kingmaker, as he was responsible for Roosevelt's rise to the presidency.[1] He was the campaign manager for New York State politician Alfred E. Smith's 1922 gubernatorial campaign and Roosevelt's 1928 and 1930 gubernatorial campaigns as well as Roosevelt's presidential campaigns of 1932 and 1936. Farley predicted large landslides in both, and revolutionized the use of polling data. He was also a business executive and dignitary.

Farley was responsible for pulling together the New Deal Coalition of Catholics, labor unions, African Americans, and farmers. Both he and the administration's patronage machine over which he presided helped to fuel the social and infrastructure programs of the New Deal. He handled most mid-level and lower-level appointments, in consultation with state and local Democratic organizations.[2] He opposed Roosevelt for breaking the two-term tradition of the presidency; the two broke on that issue in 1940. As of 1942, Farley was considered the supreme Democratic Party boss of New York.[3]

As dignitary, Farley helped to normalize diplomatic relations with the Holy See, and in 1933 he was the first high-ranking government official to travel to Rome, where he had an audience with Pope Pius XI and dinner with Cardinal Pacelli (future Pope Pius XII).[4] In business, Farley guided and remained at the helm of Coca-Cola International as chairman for over 30 years, and was responsible for the company's global expansion as a quasi-government agency in World War II. Coca-Cola ("Coke"), shipped with food and ammunition as a "war priority item", was used as a boost to the morale and energy levels of the fighting men, in a deal that spread Coke's market worldwide at government expense. Also at US expense, after the war, 59 new Coke plants were installed to help rebuild Europe.[citation needed]

In 1947, President Harry S. Truman appointed Farley to serve a senior post as a commissioner on the Hoover Commission, also known as the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government. The landmark James A. Farley Building in New York City is designated in his honor and as a monument to his career in public service.[5]

Early life

[edit]He was born in Grassy Point, New York,[6] one of five sons whose grandparents were Irish Catholic immigrants. His father, James Farley, was involved in the brick-making industry, first as a laborer and later as a part-owner of three small schooners engaged in the brick-carrying trade. His mother was the former Ellen Goldrick.

After his father died suddenly, Farley helped his mother tend a bar and grocery store that she purchased to support the family. After graduating from high school, he attended Packard Business College in New York City to study bookkeeping and other business skills. After his graduation, he was employed by the United States Gypsum Corporation.

Early political career

[edit]In 1911, Farley officially began his service as a politician, when he was elected town clerk of Stony Point, New York. Despite Stony Point's Republican leanings, Farley was reelected twice. He was elected chairman of the Rockland County Democratic Party in 1918, and he used the position to curry favor with Tammany Hall boss Charles F. Murphy by convincing him that Alfred E. Smith would be the best choice for governor. Farley married the former Elizabeth A. Finnegan on April 28, 1920. They had two daughters and one son, Elizabeth, Ann, and James A. Farley Jr.

Farley managed to secure the upstate vote for Smith north of the Bronx line, when he ran for governor the same year. The Democrats could not win north of the Bronx line before Farley organized the Upstate New York Democratic organization. After helping Smith become Governor of New York State, Farley was awarded the post of Port Warden of New York City. He was the last Democrat to hold the post, which was later taken over by the Port Authority of New York.

Farley ran for the New York State Assembly in 1922 and won in Rockland County, normally a solid Republican stronghold. He sat in the 146th New York State Legislature in 1923, but he lost it at the next election for having voted "wet," for the repeal of the Mullan–Gage Act, the state law to enforce Prohibition.

Farley was appointed to the New York State Athletic Commission at the suggestion of State Senator Jimmy Walker in 1923, and Farley served as a delegate to the 1924 Democratic National Convention, where he befriended Roosevelt, who would give his famous "Happy Warrior" speech for Smith.

Farley fought for civil rights for black Americans as chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission. In 1926, Farley threatened to resign his post as Athletic Commissioner if boxing champion Jack Dempsey did not fight the mandatory challenger, African-American fighter Harry Wills. Farley banned Dempsey from fighting Gene Tunney and publicly threatened to revoke Tex Rickard's Madison Square Garden license if he ignored the ruling of the commission.

Farley's public stand for black rights proved to be a valuable asset to the Democratic Party for generations, and it would sow the seeds of the black bloc of the New Deal.[7]

Meanwhile, Farley merged five small building supply companies to form General Builders Corporation, which would become the city's largest building supply company. Farley's firm was awarded federal contracts under the Republican Hoover administration to supply building materials to construct buildings now considered landmarks, such as the Annex of the James A. Farley Post Office Building, in New York City. General Builders supplied materials for the construction of the Empire State Building as well. Farley was an appointed official and resigned his post at General Builders when he joined Roosevelt's cabinet.

Roosevelt's campaign manager

[edit]

After some convincing from Farley and longtime FDR confidant Louis McHenry Howe, Roosevelt asked Farley to run his 1928 campaign for the New York governorship. Farley orchestrated Roosevelt's narrow victory in the 1928 gubernatorial election. Farley was named secretary of the New York State Democratic Committee and orchestrated Roosevelt's reelection in 1930. He was named chairman of the New York State Democratic Committee, which he held until his resignation, in 1944. Farley helped bring to Roosevelt's camp the powerful newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst and helped Roosevelt win the 1932 presidential nomination and election.

Farley's ability to gather the Catholics, unions, and big city machines, while maintaining the Solid South, into the New Deal Coalition greatly helped Roosevelt. Farley would repeat the process in 1936 when he correctly predicted the states Roosevelt would carry and the only two states he would lose: "As Maine goes, so goes Vermont." That prediction secured Farley's reputation in American history as a political prophet.[8] Time magazine said Farley's greatest feat of 1936 was pulling the black vote away from what had been a Republican stronghold since the time of Abraham Lincoln.

New Deal

[edit]Known as the "muscle" of the New Deal[9] and one of the architects of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA). Farley, in accordance with political tradition, was appointed by Roosevelt as Postmaster General, a post traditionally given to the campaign manager or an influential supporter, and Roosevelt also took the unusual step of naming him chairman of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) in addition to the cabinet post in 1933. Farley was constantly criticized by Roosevelt's opposition for insisting on keeping both posts simultaneously. He expanded the DNC, adding divisions to deal with women, labor unions and blacks.[10]

Farley worked hard to keep the Post Office going through the Depression. His expert stewardship made the once-unprofitable Post Office Department begin to turn a profit. Farley was instrumental in revolutionizing transcontinental airmail service and reorganized the Post Office's airmail carriers. Farley worked in concert with Pan American World Airways' (Pan Am) president, Juan Trippe, to see that the mail was delivered safely and cost-effectively. That was after a brief period of the Army carrying the mail, with servicemen killed flying in bad weather. Farley oversaw and was responsible for the flight of the first China Clipper.

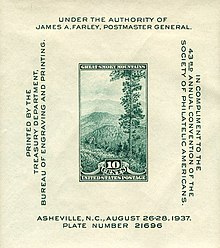

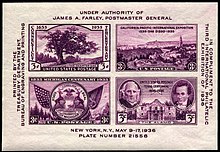

Farley's role is remembered among stamp collectors for two things. One is a series of souvenir sheets that were issued at commemorative events and bore his name as the authorizer. The other is the 20 stamps, known as "Farley's Follies", which were reprints, mostly imperforate and ungummed, of stamps of the period: Farley bought them at face value, out of his own pocket, and gave them to Roosevelt and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, both collectors, and to members of his family and special friends of the Administration. (Farley himself did not collect stamps.) Unfortunately, some of them reached the market, offered at the high prices commanded by rarities. When ordinary stamp collectors learned of that, they lodged strenuous protests, newspaper editorials leveled charges of corruption, and a heated Congressional investigation ensued. Finally, in 1935 many more of the unfinished stamps were produced and made generally available to collectors at their face value.[13]

Today, the souvenir sheets and the single cutout reprints are not scarce. The original sheets were autographed to distinguish them from the reprints, and 15 were displayed in an exhibit at the Smithsonian's National Postal Museum in June 2009.

Farley controlled federal patronage in the new administration and was very influential within Roosevelt's Brain Trust and the Democratic Party throughout the United States. Farley used his control of the patronage to see that Roosevelt's first 100 days of New Deal legislation was passed. Farley masterfully used the patronage machine to line up support for the New Deal's liberal programs.

He helped to bring about the end to Prohibition and the defeat of the Ludlow Amendment. The latter was an attempt by opponents of the war to limit the foreign affairs powers of the president by requiring a referendum for a declaration of war unless there was an attack. By swaying the votes of the Irish Catholic legislators in Congress, Farley was able to bring about a defeat for the amendment, which if passed, would have prevented the President from sending military aid to Britain. Many Irish legislators had refused to lend aid to the British because of the Great Famine.

By the late 1930s, Farley's close relationship with Roosevelt began to deteriorate. In 1938, for example, the president rebuffed his proposed prosecution of Mayor Frank Hague of Jersey City because of compelling evidence that one of Hague's functionaries was reading the mail of Hague's opponents. Roosevelt responded: “Forget prosecution. You go tell Frank to knock it off. … But keep this quiet. We need Hague’s support and we want New Jersey.” [14]

In 1940, Farley began seeking support for a presidential bid of his own after Roosevelt refused to publicly seek a third term but indicated that he could not decline the nomination if his supporters drafted him at the 1940 convention.

As chairman of the Democratic National Committee, Farley had no legitimate candidate. Roosevelt would publicly support Cordell Hull after privately telling Farley and others that they could seek the nomination.

Farley also opposed the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937 to "pack" the Supreme Court. In all other instances, however, he was continuously loyal and supportive of Roosevelt's policies. Farley was asked by Roosevelt to seek the governorship of New York multiple times but always refused.

Eleanor Roosevelt flew to the convention to try to repair the damage in the Roosevelt-Farley relationship. Although Farley remained close to her and to James Roosevelt, he felt betrayed by the President and refused to join his 1940 campaign team.

Farley believed in fair play and Equal Rights and in 1940 as Postmaster General he authorized the first postage stamp featuring the likeness of a black American Booker T. Washington whom Farley publicly hailed as the "Negro Moses".[15] This effort was spearheaded by Eleanor Roosevelt as well as others. The first Booker T. Washington stamp was sold by Farley to George Washington Carver at Tuskegee (Ala.) Institute on April 7, 1940.[16] Farley also appeared as a featured speaker at the American Negro Exposition, also known as the Black World's Fair and the Diamond Jubilee Exposition, which was a world's fair held in Chicago from July until September in 1940, to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the end of slavery in the United States at the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865.[17]

Farley resigned as postmaster general and party chairman after placing second in delegates at the 1940 Democratic National Convention in Chicago in which Roosevelt was "drafted" for a third term. Farley is the second Roman Catholic in American history to have his name placed as a candidate for nomination of the presidency by a major political Party (Al Smith being the first). He was the first Irish-American Catholic to achieve success as a national figure when Roosevelt appointed Farley to his cabinet and chairman of the Democratic National Committee. The Postmaster General at that time was 5th in line to the Presidency.

Later life

[edit]After leaving Washington in 1940, Farley was named chairman of the board of the Coca-Cola Export Corporation, a vehicle that was created for his talents. Farley held this post until his retirement in 1973. Farley defeated a Roosevelt bid to name the party's candidate for New York governor in 1942. Farley once again became an important national political force when his old friend, Harry Truman, became president in 1945.

On October 26, 1963, Tuskegee University conferred upon Farley the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws for his "many contributions to public life"[18] and for his "distinguished possession of the private personal virtues."[19]

In 1965 Farley served as the campaign chairman for the failed first Mayoral bid of Abraham Beame who would go on to be the first practicing Jewish Mayor of New York in 1973.[20] Farley was given in 1974 the Laetare Medal by the University of Notre Dame, the oldest and most prestigious award for American Catholics.[21]

On June 9, 1976, Farley died in his suite at the Waldorf Astoria, where he was one of the landmark's most notable residents for many years. He remained vigorous, outspoken, and active in politics until the end of his life, and when he died, he was found "dressed as if he were planning to go out".[22] The last surviving member of Roosevelt's cabinet, he was interred at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Hawthorne, New York.

Legacy

[edit]Farley, the former chairman of Coca-Cola Export, was the only man to serve as National Party Chairman, New York State Party Chairman, and Postmaster General simultaneously. Farley's respect crossed party lines. Towards the end of his career, Farley was an elder statesman and pushed for campaign finance reform and a reduction of the influence of special interest groups and of corporations in politics.

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York named Farley as one of its "Bicentennial People/Innovator" in commemoration of its 200-year anniversary in 2007.

- The James A. Farley Award is the Boxing Writers Associations highest honor, awarded to those who exhibit honesty and integrity in the sport of boxing.

- Farley's Box is the name given to a group of front row seats along Yankee Stadium's first base line, which was frequented by Farley and many famous VIPs and guests. In later years, Farley would donate those tickets to Boys Clubs in New York City and the surrounding areas.

- Farley was also the first guest on NBC's Meet the Press, the longest-running show in television history.

- Farley is also known for his eponymous device, the Farley file.

- In 1962, Farley received The Hundred Year Association of New York's Gold Medal Award "in recognition of outstanding contributions to the City of New York."

- Farley's Law is that it is by mid-October that voters will decide the presidential candidate they are most likely to vote for.

- As explained in the book How to Win Friends and Influence People, Farley was known for his ability to remember names and details of almost every person he met.

Namesakes

[edit]- James Farley Building, New York City Landmark, National Register of Historic Places

- James A. Farley elementary school, Stony Point, New York

- James A. Farley memorial bridge, Stony Point, New York

- Farley file

References

[edit]- ^ Farley Dies – Jun 10, 1976 – NBC – TV news: Vanderbilt Television News Archive. Tvnews.vanderbilt.edu (June 10, 1976). Retrieved on July 26, 2013.

- ^ Daniel Mark Scroop, Mr. Democrat: Jim Farley, the New Deal and the Making of Modern American Politics (University of Michigan Press, 2006)

- ^ "The Nation: Farley Wins". Time. August 31, 1942. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Full text of "Jim Farley S Story". Archive.org. Retrieved on July 26, 2013.

- ^ Bill Summary & Status – 97th Congress (1981 – 1982) - H.RES.368 – THOMAS (Library of Congress) Archived July 15, 2012, at archive.today. Thomas.loc.gov. Retrieved on July 26, 2013.

- ^ James A Farley (1938), Behind The Ballots, Harcourt, Brace, and Co. pg 3, ASIN B00126SYSQ

- ^ "DEMOCRATS: Portents & Prophecies". Time. October 31, 1932. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ 1952 Presidential Election Race: Eisenhower v Stevenson – Video Dailymotion. Dailymotion.com (October 1, 2010). Retrieved on July 26, 2013.

- ^ Whitman, Alden (June 10, 1976). "Farley, 'Jim' to Thousands, Was the Master Political Organizer and Salesman". The New York Times.

- ^ Daniel Scroop, Mr. Democrat: Jim Farley, the New Deal, and the Making of Modern American Politics (2006) p. 100.

- ^ Young, William H.; Young, Nancy K. (2007). The Great Depression in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313335228.

- ^ Young, William H.; Young, Nancy K. (2007). The Great Depression in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313335228.

- ^ Young, William H.; Young, Nancy K. (2007), The Great Depression in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia (illustrated ed.), Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 520–522, ISBN 978-0-313-33520-4

- ^ Beito, David T. (2023). The New Deal's War on the Bill of Rights: The Untold Story of FDR's Concentration Camps, Censorship, and Mass Surveillance (First ed.). Oakland: Independent Institute. p. 63. ISBN 978-1598133561.

- ^ "Farley Sells First B.T. Washington Stamp and Lauds 'Negro Moses' at Tuskegee". The New York Times. April 8, 1940.

- ^ "Jet". Johnson Publishing Company. April 11, 1963.

- ^ Congress, United States (1940). "Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress".

- ^ Congress, United States (1963). "Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress".

- ^ Congress, United States (1963). "Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the ... Congress".

- ^ https://www.jfklibrary.org/sites/default/files/archives/RFKOH/Beame%2C%20Abraham%20D/RFKOH-ADB-01/RFKOH-ADB-01-TR.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Recipients | The Laetare Medal". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ "James A. Farley, 88, Dies; Ran Roosevelt Campaigns". The New York Times. June 10, 1976. p. 1. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Scroop, Daniel "Mr. Democrat: Jim Farley, The New Deal, and The Making of Modern American Politics."]

- Sheppard, Si. Buying of the Presidency?, The: Franklin D. Roosevelt, the New Deal, and the Election of 1936 (ABC-CLIO, 2014).

- Spencer, Thomas T. "'Old' Democrats and New Deal Politics: Claude G. Bowers, James A. Farley, and the Changing Democratic Party, 1933–1940" Indiana Magazine of History 1996 92(1): 26–45. ISSN 0019-6673

Primary sources

[edit]- Farley, James A. Jim Farley's Story: The Roosevelt Years (1948)

- Farley, James A. Behind the Ballots: The Personal History of a Politician (1938)

External links

[edit]- USPS James A. Farley Bio.

- An Interview with Farley (1959) on Folkways Records

- James Farley biography at the National Park Service website

- Bill designating Landmark General Post Office the "James A. Farley Building" Archived July 15, 2012, at archive.today

- The short film OPEN MIND Special: March 4, 1933 (1992) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Longines Chronoscope with James A. Farley (August 25, 1952) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The short film Longines Chronoscope with James A. Farley (September 15, 1952) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Newspaper clippings about James Farley in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1888 births

- 1976 deaths

- 1940 United States vice-presidential candidates

- 20th-century American politicians

- American autobiographers

- American campaign managers

- American people of Irish descent

- Burials at Gate of Heaven Cemetery (Hawthorne, New York)

- Candidates in the 1940 United States presidential election

- Candidates in the 1944 United States presidential election

- Catholics from New York (state)

- Democratic National Committee chairs

- Franklin D. Roosevelt administration cabinet members

- Laetare Medal recipients

- Democratic Party members of the New York State Assembly

- People from Stony Point, New York

- United States postmasters general

- Writers from New York City

- New York State Athletic Commissioners