Russian Academy of Sciences

| |

| Established | 8 February 1724 Saint Petersburg, Russia |

|---|---|

| President | Gennady Krasnikov[1] (since September 20, 2022) |

| Members | 1900 Russian + about 440 foreign, See also § Institutions |

| Address | Leninsky prospekt 14, Moscow |

| Location | Russia |

| Website | www |

Building details | |

| |

| |

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; Russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk) consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across the Russian Federation; and additional scientific and social units such as libraries, publishing units, and hospitals.

Peter the Great established the academy (then the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences) in 1724 with guidance from Gottfried Leibniz.[2] From its establishment, the academy benefitted from a slate of foreign scholars as professors; the academy then gained its first clear set of goals from the 1747 Charter.[2][3] The academy functioned as a university and research center throughout the mid-18th century until the university was dissolved, leaving research as the main pillar of the institution.[2] The rest of the 18th century continuing on through the 19th century consisted of many published academic works from Academy scholars and a few Academy name changes, ending as The Imperial Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences right before the Soviet period.[2][4]

Now headquartered in Moscow, the academy (RAS) is a non-profit organization established in the form of a federal state budgetary institution[5] chartered by the Government of Russia. In 2013, the Russian government restructured RAS, assigning control of its property and research institutes to a new government agency headed by Mikhail Kotyukov.

As of November 2017[update], the academy included 1,008 institutions and other units;[6] in total about 125,000 people were employed of whom 47,000 were scientific researchers.[7]

Membership

[edit]There are three types of membership in the RAS: full members (academicians), corresponding members, and foreign members. Academicians and corresponding members must be citizens of the Russian Federation when elected. However, some academicians and corresponding members were elected before the collapse of the USSR and are now citizens of other countries. Members of RAS are elected based on their scientific contributions – election to membership is considered very prestigious.[8]

In the years 2005–2012, the academy had approximately 500 full and 700 corresponding members. But in 2013, after the Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences became incorporated into the RAS, a number of the RAS members accordingly increased. The last elections to the renewed Russian Academy of Sciences were organized from May 30 to June 3, 2022.[9]

As of end April 2024, the academy had 1900 living Russian members (full: 819, corresponding: 1081) and about 440 foreign members.

Since 2015, the academy also awards, on a competitive basis, the honorary scientific rank of a RAS Professor to the top-level researchers with Russian citizenship. Now there are 713 scientists with this rank.[10][11][12] RAS professorship is not a membership type but its holders are considered as possible candidates for membership; some professors became members already in 2016, in 2019 or in 2022 and are henceforth titled "RAS professor, corresponding member of the RAS" (163 scientists) or even "RAS professor, academician of the RAS" (16 scientists).

Present structure

[edit]The RAS consists of 13 specialized scientific divisions, four territorial branches and 15 regional scientific centers. The academy has numerous councils, committees, and commissions, all organized for different purposes.[13]

Territorial branches

[edit]- Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (SB RAS)

- The Siberian Branch was established in 1957, with Mikhail Lavrentyev as founding chairman. Research centers are in Novosibirsk (Akademgorodok), Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, Yakutsk, Ulan-Ude, Kemerovo, Tyumen and Omsk. As of end-2017, the Branch employed over 12,500 scientific researchers, 211 of whom were members of the Academy (109 full + 102 corresponding).[14]

- Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (UB RAS)

- The Ural Branch was established in 1932, with Alexander Fersman as its founding chairman. Research centers are in Yekaterinburg, Perm, Cheliabinsk, Izhevsk, Orenburg, Ufa and Syktyvkar. As of 2016, 112 Ural scientists were members of the Academy (41 full + 71 corresponding).[15]

- St. Petersburg Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (SPbB RAS)

- The St. Petersburg Branch was established in 2023. As of October 1, 2024, 178 scientists from St. Petersburg were members of the Academy (70 full + 108 corresponding).[16]

- Far East Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (FEB RAS)

- The Far East Branch includes the Primorsky Scientific Center in Vladivostok, the Amur Scientific Center in Blagoveschensk, the Khabarovsk Scientific Center, the Sakhalin Scientific Center in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, the Kamchatka Scientific Center in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, the North-Eastern Scientific Center in Magadan, the Far East Regional Agriculture Center in Ussuriysk and several Medical institutions. As of 2017, there were 64 Academy members in the Branch (23 full + 41 corresponding).[17][18]

Regional centers

[edit]

- Kazan Scientific Center

- Pushchino Scientific Center

- Samara Scientific Center

- Saratov Scientific Center

- Vladikavkaz Scientific Center of the RAS and the Government of the Republic Alania – Northern Ossetia

- Dagestan Scientific Center

- Kabardino-Balkarian Scientific Center

- Karelian Research Centre of RAS

- Kola Scientific Center

- Nizhny Novgorod Center

- Scientific Center of the RAS in Chernogolovka

- St. Petersburg Scientific Center

- Ufa Scientific Center

- Southern Scientific Center

- Troitsk Scientific Center

Institutions

[edit]This section's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2015) |

The Russian Academy of Sciences comprises a large number of research institutions, including:

- Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics

- Central Economic Mathematical Institute CEMI

- Dorodnitsyn Computing Centre

- Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology

- Institute for Medical Science (Russia)[19]

- Institute for African Studies (Moscow)[20]

- Institute of Far Eastern Studies[21]

- Institute for Economic Strategies (Moscow)[22]

- Institute for the History of Material Culture (St Petersburg)[23]

- Institute of Archaeology (Moscow)[24]

- Institute for Physics of Microstructures[25]

- Institute for Slavic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- Institute for Spectroscopy

- Institute for System Programming

- Institute of Applied Physics[26]

- Institute of Cell Biophysics

- Institute of Biological Instrumentation

- Institute of Biomedical Problems

- Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine (Novosibirsk)

- Institute of Ecology and Evolution

- Institute of Economy (RAS)

- Institute of Human Brain (St.-Petersburg)

- Institute of Gene Biology

- Institute of Silicate Chemistry

- Institute of High Current Electronics

- Institute of Latin American Studies (Moscow)[27]

- Institute of Linguistics (Moscow)

- Institute for Linguistic Studies (Saint Petersburg)

- Institute of Oriental Studies (Moscow)

- Institute of Oriental Manuscripts (Saint Petersburg)

- Institute of Philosophy

- Institute of Plant and Animal Ecology

- Institute of Radio-engineering and Electronics

- Institute of Solid State Physics

- Institute of State and Law

- Institute of the US and Canada (ISKRAN)

- Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO)

- Institute of World Literature (Moscow)

- Ioffe Physico-Technical Institute

- Keldysh Institute of Applied Mathematics

- Komarov Botanical Institute

- Komi Science Centre[28]

- Kutateladze Institute for Thermal Physics

- Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics

- Laser and Information Technology Institute

- Lebedev Institute of Precision Mechanics and Computer Engineering

- Lebedev Physical Institute

- N.N. Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology

- A.N. Nesmeyanov Institute of Organoelement Compounds

- Northeast Science Station (Северо-Восточная научная станция РАН)

- Obukhov Institute of Atmospheric Physics

- Paleontological Institute

- Program Systems Institute[29]

- A. M. Prokhorov General Physics Institute

- Pushkov Institute of Terrestrial Magnetism, Ionosphere and Radiowave Propagation (IZMIRAN)

- Schmidt Institute of the Physics of the Earth

- Space Research Institute

- Shemyakin and Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, which has an artificial climate station called "biotron"[30]

- Shirshov Institute of Oceanology

- Shubnikov Institute of Crystallography RAS

- Special Astrophysical Observatory

- State Public Scientific & Technological Library

- Steklov Institute of Mathematics

- St. Petersburg Department of Steklov Institute of Mathematics

- Sukachev Institute of Forest

- Vernadsky Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry

- Vingoradov Russian Language Institute

- Institute of Scientific Information on Social Sciences

- N. D. Zelinsky Institute of Organic Chemistry[31]

- Zoological Institute[32]

Member institutions are linked via a dedicated Russian Space Science Internet (RSSI). Started with just three members, The RSSI now has 3,100 members, including 57 from the largest research institutions.

Russian universities and technical institutes are not under the supervision of the RAS (they are subordinated to the Ministry of Education of Russian Federation), but a number of leading universities, such as Moscow State University, St. Petersburg State University, Novosibirsk State University, and the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, make use of the staff and facilities of many institutes of the RAS (as well as of other research institutions); the MIPT faculty refers to this arrangement as the "Phystech System".

From 1933 to 1992, the main scientific journal of the Soviet Academy of Sciences was the Proceedings of the USSR Academy of Sciences (Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR); after 1992, it became simply Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences (Doklady Akademii Nauk).

The academy is also increasing its presence in the educational area. In 1990, the Higher Chemical College of the Russian Academy of Sciences was founded, a specialized university intended to provide extensive opportunities for students to choose an academic path.

Awards

[edit]The academy gives out a number of different prizes, medals and awards among which:[33]

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2011) |

In the Russian Empire

[edit]Creation of the Academy

[edit]

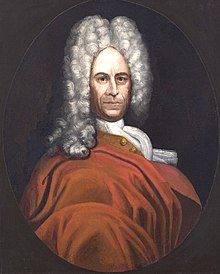

The academy was a culmination of Emperor Peter the Great's inspiration from his tours to Western Europe and its higher education centers along with the beginning of his correspondence with Gottfried Leibniz, a philosopher, mathematician, and diplomat.[3][34] Peter's Western European travels introduced him to the new inventions and ideas of the Enlightenment period.[34] Leibniz was attracted to Peter's desire to promote education and science in Russia through modernization of the academic system as he had seen in Western Europe, although he could not get a meeting with Peter during Peter's first European tour.[3][34] Leibniz did, however, begin correspondence with Peter's advisors where he discussed different plans to achieve the westernization of Russia.[34] Leibniz suggested an education reform which divided schools, universities, and academies, as well as creating new academies and schools.[34] Also, Leibniz suggested creating an arts and sciences institution with faculty consisting of leading foreign scholars.[34]

Following Leibniz's advice, Peter founded the St. Petersburg Academy of Science a year before he died, in January 1724 and the Senate decree of February 8, 1724 implemented the academy.[5][35] It was modeled after the centralized structure of the Paris Academy and the Berlin Academy of Sciences.[3][34] These model institutions had led to an educated society of philosophical men, something Peter wanted in Russia.[36] In particular, the Berlin Academy of Sciences was founded by Leibniz, exemplary of the influence which Leibniz had on the creation of the St Petersburg Academy of Science.[36] The Paris Academy was administered directly by the King, which inspired Peter to make himself the supreme head of the St Petersburg Academy of Science, although there could be an academy president.[36][4]

Early years of the Academy

[edit]

Peter's widow and Empress Catherine I followed through with the establishment and formation of the academy, opening it in December 1725.[3] Mathematics, physical sciences, and humanities were the three departments which made up the academy upon its opening.[34] The academy also contained a university and secondary school, promoting higher education in Russia.[34][2] As such, the initial 17 scholars had to teach and administer research.[34][36] They were a portion of the 84 Academy staff in 1726[36] There were also student assistants who helped the scholars and taught in the secondary school.[37] 112 students ages 5–18 made up the total first year enrollment in 1726.[2] 76 of the 112 students were Russian while the other 36 students were foreign.[2] The academy did not have an official charter until 1747.[36] Peter I did lay out the goals for the academy in a document signed before his death called the "Project".[36] In the document, Peter wished for the academy to be a model for Russia.[36]

Since the academy was under the Tsar, the presidents, vice-presidents, directors, and vice-directors were all appointed by the crown.[2] Catherine I started this precedent which lasted until the end of the Russian Empire.[2] The academy hit hard times during Empress Anna's rule. A low of 6 students remained in 1744 and the teaching was in German, contrary to Peter I's wishes.[2] The academy achieved a major goal in the 1740s by turning out the first Russian scholar members, Stepan Krasheninnikov and Mikhail Lomonosov.[2]

Post-1747 Charter

[edit]The academy's charter in 1747 brought some changed to the academy's organization which stood until the end of the century.[3][2] Among some of the changes were Russian and Latin as the official languages, a push to translate literature into Russian, and restrictive working hours for faculty.[3][2] The charter also emphasized the hope for Russian Academy graduates to replace all the foreign scholars in time.[2] Most of the secondary school graduates went into civil service instead of continue to the university.[2] The university part of the academy gradually deteriorated and eventually died by 1767.[2]

During Catherine the Great's rule, she enacted reforms to improve the academy for scholars.[3] She created a commission of academy faculty to lead the academy instead of bureaucratic rule.[3] Also, in the second half of the 18th century, Russian scholars grew in number among the faculty of the academy.[2] To heal the growing internal German versus Russian conflict of the faculty, Catherine the Great convinced Euler to return to St Petersburg and head the academy in 1766, where he stayed until he died in 1783.[3] Catherine the Great's son Paul I's short reign marked a decline for the academy as he cut funding for academic institutions and prohibited Russians from attending Western influenced institutions.[3] In 1803, Alexander I reverted to reforms from Catherine the Great's era and gave the academy self-administration power in a new charter.[3][2] The new charter came with a name change to the Imperial Academy of Sciences.[37]

Scholars and research

[edit]

Following Leibniz's instructions, Peter reached out to the German philosopher Christian Wolff, a correspondent of Leibniz, in the early 1720s and unsuccessfully offered him the Vice-Presidency of the academy.[34] While Wolff declined a position in the academy, he did invite western scholars to work at the academy to improve higher education within the Russian Empire as outlined in Leibniz's letters.[38] Foreign scholars invited to work at the academy included the mathematicians Leonhard Euler (1707–1783),[38] Anders Johan Lexell, Christian Goldbach, Georg Bernhard Bilfinger, Nicholas Bernoulli (1695–1726) and Daniel Bernoulli (1700–1782), botanist Johann Georg Gmelin, embryologists Caspar Friedrich Wolff, astronomer and geographer Joseph-Nicolas Delisle, physicist Georg Wolfgang Kraft, historian Gerhard Friedrich Müller and English Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne (1732–1811).[38][39]

Expeditions to explore remote parts of the country had Academy scientists as their leaders or most active participants. These included Vitus Bering's Second Kamchatka Expedition of 1733–1743, expeditions to observe the 1769 transit of Venus from eight locations in Russian Empire, and the expeditions of Peter Simon Pallas (1741–1811) to Siberia. The expeditions led to the creation of an atlas of Russia and to research in astronomy, geography, and fauna and flora.[4][40] From 1750 to 1777, the academy published 20 volumes of their academic journal called Novi Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae.[2] The majority of Russian scientific research in the 18th century was done by members of the academy.[2]

Academy name changes

[edit]Originally called The Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences (Russian: Петербургская академия наук), the organization went under various names over the years, becoming The Imperial Academy of Sciences and Arts (Императорская академия наук и художеств; 1747–1803), The Imperial Academy of Sciences (Императорская академия наук; 1803–1836), and finally, The Imperial Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences (Императорская Санкт-Петербургская академия Наук, from 1836 and until the end of the empire in 1917).

| Official Academy Name | Years |

|---|---|

| The Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences | 1725–1747 |

| The Imperial Academy of Sciences and Arts | 1747–1803 |

| The Imperial Academy of Sciences | 1803–1836 |

| The Imperial Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences | 1836–1917 |

A separate organization, called the Russian Academy (Russian: Академия Российская), was created in 1783 to work on the study of the Russian language. Presided over by Princess Yekaterina Dashkova (who at the same time was the Director of the Imperial Academy of Arts and Sciences, i.e., the country's "main" academy), the Russian Academy was engaged in compiling the six-volume Academic Dictionary of the Russian Language (1789–1794). The Russian Academy was merged into the Imperial Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences in 1841.

In the Soviet Union

[edit]Shortly after the October Revolution, in December 1917, Sergey Fedorovich Oldenburg, a leading ethnographer and political activist in the Kadet party, met with Vladimir Lenin to discuss the future of the academy. They agreed that the expertise of the academy would be applied to addressing questions of state construction, while in return the Soviet government would give the academy financial and political support.

The most important activities of the academy in the 1920s included an investigation of the large Kursk Magnetic Anomaly, of the minerals in the Kola Peninsula, and participation in the GOELRO plan targeted electrification of the whole country. In 1925 the Soviet government recognized the Russian Academy of Sciences as the "highest all-Union scientific institution" and renamed it the Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union. In 1934, the academy headquarters moved from Leningrad to the capital, Moscow.

The Stalin years were marked by a rapid industrialisation of the Soviet Union for which a great deal of research, mainly in the technical fields, was done. However, on the other hand, in these very times, many scientists underwent repressions for ideological reasons.

In the years of the Second World War, the Soviet Academy of Sciences made a big contribution to a development of modern weapons – tanks (new series of T-34), airplanes, degaussing the ships (for protection against the naval mines) etc. – and therefore to victory of the USSR over Nazi Germany. During and after the war, the academy was involved in the Soviet atomic bomb project; due to its success and other achievements in military techniques, the USSR became one of the superpowers in the Cold War era.

At the end of the 1940s, the academy consisted of eight divisions (Physico-Mathematical Science, Chemical Sciences, Geological-Geographical Sciences, Biological Science, Technical Science, History and Philosophy, Economics and Law, Literature and Languages); three committees (one for coordinating the scientific work of the Academies of the Republics, one for scientific and technical propaganda, and one for editorial and publications), two commissions (for publishing popular scientific literature, and for museums and archives), a laboratory for scientific photography and cinematography and Academy of Science Press departments external to the divisions.[41]

The Academy of Sciences of the USSR helped to establish national Academies of Sciences in all Soviet republics (with the exception of the Russian SFSR), in many cases delegating prominent scientists to live and work in other republics. In the case of Ukraine, its academy was formed by the local Ukrainian scientists and prior to occupation of the Ukrainian People's Republic by Bolsheviks. These academies were:

Among the most important achievements of the academy of the second half of the 20th century, there is, first of all, the Soviet space program. In 1957 the first satellite was launched, in 1961 Yury Gagarin became the first person in space, and in 1971 the first space station Salyut 1 began its operation. Discoveries were also made in the nuclear branch and in other fields of physics. Furthermore, the academy participated in opening new universities or new study programs in the already existed universities, whose best absolvents started their career at the research institutes of the academy.

Post-Soviet period

[edit]After the collapse of the Soviet Union, by decree of the President of Russia of December 2, 1991, the academy again became the Russian Academy of Sciences,[5] inheriting all facilities of the USSR Academy of Sciences in the territory of the Russian Federation.

The crisis of the 1990s in the post-Soviet Russia and a consequent drastic reduction of the state support for science have forced many scientists to leave Russia for Europe, Israel or the United States. Some excellent university graduates who could have become promising researchers also switched to other activities, predominately in commerce. The Russian Academy practically lost a generation of people born from the mid-1960s to mid-1970s; this age category is now underrepresented in all research institutes.

In the 2000s, the situation in the Russian science and technology has improved, the government announced a modernization campaign. Nevertheless, according to the Russian Academy of Sciences, total R&D spending in 2013 still hovered about 40% below the pre-crisis 1990 levels.[42] Furthermore, a lack of competition, decayed infrastructure and continuing, though slightly reduced, brain drain play their part.

Restructured academy 2013 and later

[edit]

On June 28, 2013, the Russian Government announced a draft law that would dissolve the RAS while creating a new "public-governmental" organization with the same name. The RAS would be fused with two other Russian national academies—Russian Academy of Agricultural Sciences and Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, with all members of all academies acquiring equal status as academicians.[43]

The law also created a new government agency: Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations (FASO).[44] FASO would take control of all buildings and other property of the academy. In addition, all RAS academic institutes were removed from academy control. Instead, the new government agency FASO was empowered to "evaluate", relying on its own criteria, the efficiency of research institutes and rearrange ineffective ones.[45]

The draft law, which, in its initial form, would have fundamentally changed the system of science organization in Russia, provoked conflicts and protests within academic circles.[46] A large group of the RAS members signalized their intention not to join the new academy if the reform is run as planned in the draft.[47] Some leading scientists (including Pierre Deligne, Michael Atiyah, Mumford, and others) wrote open letters which referred to the planned reform of the RAS as "shocking" and even "criminal".[48] In this situation, the draft was softened in some details—e.g., there remained no words about "dissolution" in the text—and approved on September 27, 2013. In 2014, Putin announced more changes to science funding that reduced RAS power while increasing that of the government.[49]

In 2017, the election of the RAS president was also brought under government control.[50][51] At the General Meeting of the RAS in March 2018, the RAS president (that time) Alexander Sergeev said that the academy enters now the post-reform period.[52]

In May 2018, the FASO was incorporated into Russia's new Ministry of Science and Higher Education. The latter was created by splitting the Ministry of Education and Science. Mikhail Kotyukov, who had been head of FASO since its creation, was named head of the new Ministry of Science and Higher Education.[53][54]

In June 2023, the RAS opened the Modern Ideology of China Research Laboratory within its Institute of China and Contemporary Asia to study Xi Jinping Thought.[55]

Presidents

[edit]Imperial Russia

[edit]The following persons occupied the position of the academy's President (or, sometimes, Director):[56][57]

- Laurentius Blumentrost, 1725–1733

- Hermann Karl von Keyserling 1733–1734

- Johann Albrecht Korf, 1734–1740

- Karl von Brevern, 1740–1741

- (Post vacant, April 1741 – October 1746)

- Count Kirill Razumovsky, 1746–1766 (nominally, till 1798)

- Count Vladimir Orlov, 1766–1774 (Director)[58][59]

- Alexey Rzhevsky, 1771–1773 (Occasional Substitute of Orlov )[60]

- Sergey Domashnev, 1775–1782 (Director)[58][61]

- Princess Yekaterina Vorontsova-Dashkova, 1783–1796 (Director; sent into de facto retirement in 1794. Simultaneously served as the President of the Russian Academy)[62]

- Pavel Bakunin, 1794–1796 (acting Director), 1796–1798 (Director). Simultaneously served as the President of the Russian Academy

- Ludwig Heinrich von Nicolay, 1798–1803

- Nikolay Novosiltsev, 1803–1810

- (Post vacant, April 1810 – Jan 1818)

- Count Sergey Uvarov, 1818–1855

- Dmitry Bludov, 1855–1864

- Fyodor Litke, 1864–1882

- Count Dmitry Tolstoy, 1882–1889

- Grand Duke Constantine Constantinovich of Russia, 1889–1915

- (Post vacant, June 1915 – May 1917)

Soviet Russia

[edit]- Alexander Karpinsky, 1917–1936

- Vladimir Komarov, 1936–1945

- Sergey Vavilov, 1945–1951

- Alexander Nesmeyanov, 1951–1961

- Mstislav Keldysh, 1961–1975

- Anatoly Alexandrov, 1975–1986

- Gury Marchuk, 1986–1991

Russian Federation

[edit]- Yury Osipov, 1991–2013

- Vladimir Fortov, 2013–2017

- Valery Kozlov, 2017 (acting)

- Alexander Sergeev, 2017–2022

- Gennady Krasnikov, since Sept 2022

The last presidential elections in the academy (and also elections of the presidium) were organized on September 25–28, 2017. Initially the event was planned for March 2017, but unexpectedly all candidates retracted their nominations, and the elections were postponed.[63]

Achievements

[edit]Social activities of the academy and its members

[edit]

Scientists of the academy were repeatedly elected deputies of various levels. In the Supreme Soviet of the USSR in 1974, "among the deputies of the Council of the Union, there were 22 scientists from the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, the academies of sciences of the Union republics, and branch academies."[64] In 1989, Andrei Sakharov became a People's Deputy of the USSR. Many scientists have worked in the State Duma of the Russian Federation - among the most famous are the physicist Zhores Alferov (deputy from the Communist Party of the Russian Federation until his death on March 1, 2019, initiator of the laws "On Education for All" and "On Support for Innovation in Russia"), physician Gennady Onishchenko (from United Russia, member of the committee on education and science), and polar explorer Artur Chilingarov (United Russia).[65]

Nobel Prize laureates affiliated with the Academy

[edit]- Ivan Petrovich Pavlov, medicine, 1904

- Ilya Ilyich Mechnikov, medicine, 1908

- Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin, literature, 1933

- Nikolay Nikolayevich Semyonov, chemistry, 1956

- Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm, physics, 1958

- Ilya Mikhailovich Frank, physics, 1958

- Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov, physics, 1958

- Lev Davidovich Landau, physics, 1962

- Nikolay Gennadiyevich Basov, physics, 1964

- Aleksandr Mikhailovich Prokhorov, physics, 1964

- Mikhail Aleksandrovich Sholokhov, literature, 1965

- Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn, literature, 1970

- Leonid Vitaliyevich Kantorovich, economics, 1975

- Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov, peace, 1975

- Pyotr Leonidovich Kapitsa, physics, 1978

- Zhores Ivanovich Alferov, physics, 2000

- Alexei Alexeyevich Abrikosov, physics, 2003

- Vitaly Lazarevich Ginzburg, physics, 2003

- Andre Geim, physics, 2010

See also

[edit]- Academy of Sciences Glacier

- Academy of Sciences Range

- Akademgorodok in Krasnoyarsk

- Akademgorodok in Novosibirsk

- Akademgorodok in Tomsk

- Lev Davidovich Belkind has released a number of books on the unique contribution of Russian scientists and engineers to the technological progress.

- Neuro-linguistic programming

- Constitutional economics

- Energy Research Institute of Russian Academy of Sciences

- Kamchatka Volcanic Eruption Response Team

- Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- List of Russian explorers

- List of Russian inventors

- List of Russian scientists

- MARS-500

- Nauka, RAS publishing division

- Open access in Russia

- Pushchino Radio Astronomy Observatory

- Timeline of Russian inventions and technology records

- VINITI Database RAS

- Named prizes and medals of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences

References

[edit]- ^ "Gennady Krasnikov elected new President of the Russian Academy of Sciences". Novye Izvestia. 2022-09-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Schulze, Ludmilla (1985). "The Russification of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences and Arts in the Eighteenth Century". The British Journal for the History of Science. 18 (3): 305–335. doi:10.1017/S0007087400022408. ISSN 0007-0874. JSTOR 4026383. PMID 11620800. S2CID 36141079.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "The St. Petersburg Academy". eulerarchive.maa.org. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- ^ a b c "The first session of the Emperor Academy in St.-Petersburg took place". Presidential Library. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ^ a b c General information about the Academy. (in Russian).

- ^ Official list of units under jurisdiction of the Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations (these are units of RAS), 27 October 2017, in Russian.

- ^ Report of the Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations Archived 2017-04-03 at the Wayback Machine (number of employees: page 8), 20 March 2017, (in Russian).

- ^ Academy membership (in Russian)

- ^ Выборы в Российскую академию наук – 2022 [Elections to the Russian academy of sciences - 2022] (in Russian). RAS website. Retrieved 2022-06-06.

- ^ Постановления президиума РАН о присвоении звания "Профессор РАН" (in Russian).

- ^ Присвоение званий "Профессор РАН" в 2018 году [Awarding the RAS Professor ranks in 2018] (in Russian).

- ^ Присвоение званий "Профессор РАН" в 2022 году [Awarding the RAS Professor ranks in 2022] (in Russian).

- ^ Academy structure (in Russian)

- ^ "About the Siberian Branch". Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "About the Ural Branch (2016 year report)" (PDF). Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "On October 24, the general meeting of the St. Petersburg branch of the Academy takes place". Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ "Scientific Centers and Institutes of the Far East Branch". Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ "Academy members of the Far East Branch". Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ http://www.kbsu.in [bare URL]

- ^ "Institute for African Studies | of the Russian Academy of Sciences".

- ^ https://www.ifes-ras.ru/ [bare URL]

- ^ "Институт Экономических Стратегий - ENG". Archived from the original on 2006-05-16.

- ^ "Institute for the History of Material Culture of Russian Academy of Sciences". Archived from the original on 2012-01-27.

- ^ "Home | Институт археологии Российской академии наук".

- ^ http://ipmras.ru/en/index [bare URL]

- ^ "IAP RAS - General Information".

- ^ "Ила Ран".

- ^ "Russian Academy of Sciences, Ural Division, Komi Science Centre". KomiSC.ru. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016.

- ^ "The Program Systems Institute of RAS".

- ^ "Artificial Climate Station "Biotron"". Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- ^ https://zioc.ru/ [bare URL]

- ^ "Zoological Institute RAS - Home".

- ^ "Именные премии и медали". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rosa Massa-Esteve, M. "The impact of the relationship between Peter I and Leibniz on the development of science in Russia" (PDF). Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

- ^ Sagdeyev, R. Z.; Shtern, M. I. The Conquest of Outer Space in the USSR 1974. NASA Technical Reports Server (Report). hdl:2060/19770010175.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gordin, Michael D. (2000). "The Importation of Being Earnest: The Early St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences". Isis. 91 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1086/384624. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 237556. S2CID 144136124.

- ^ a b "Imperial Academy of Sciences of St. Petersburg". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ^ a b c Calinger, Ronald (1996). "Leonhard Euler: The First St. Petersburg Years (1727–1741)". Historia Mathematica. 23 (2): 125. doi:10.1006/hmat.1996.0015.

- ^ "Papers of Nevil Maskelyne: Certificate and seal from Catherine the Great, Russia". University of Cambridge Digital Library. Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "Russian Academy of Sciences". Saint Petersburg Encyclopedia. October 24, 2022.

- ^ Ashby, Eric. 1947. "Scientist in Russia". Pelican books

- ^ O. Dobrovidova (2016-09-01). "Russia: A faltering recovery". Nature. 537 (7618): S10–S11. Bibcode:2016Natur.537S..10D. doi:10.1038/537S10a. PMID 27580133.

- ^ Stone, Richard (11 February 2014). "Embattled President Seeks New Path for Russian Academy". Science. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

Last month, the powerful Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) was compelled to merge with two sister academies that serve medical and agricultural research. The reform law setting that change in motion also created a Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations (FASO) that oversees the combined academies and their assets.

- ^ "Inside Look: The Russian intelligentsia in revolt". Russia Direct. 16 July 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

The essence of the reform is that the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Academy of Medical Sciences and the Academy of Agricultural Sciences will be merged into a single 'Super Academy.' Control over academic institutions will be handed to a new state agency that will report to the government. This change implies that the current Academy will lose its main privilege, which is to independently spend the money allocated from the federal budget. This lost privilege would essentially turn the Academy into an 'academic club.'

- ^ "Russian Academy of Sciences awaits reform". Russia Direct. 5 July 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

Putin also called to Fortov's attention that the reform asks for "the establishment of an agency managing Academy assets and essentially performing one of its main functions - the appointment of academic institute directors and, to a considerable degree, the evaluation of their performance."

- ^ "Editorial: Russian roulette". Nature. 499 (7456): 5–6. 3 July 2013. doi:10.1038/499005b. PMID 23841154. S2CID 56201926.

The planned coup would merge the Academy of Sciences with Russia's minor medical and agricultural academies, and would provide all members of the united body with equal status as academicians. The present academy would lose the right to manage its property and, more importantly, would cease to operate research institutes of its own. Existing institutes would be evaluated, and those deemed competitive would in future be run by a new government agency on behalf of the academy.

- ^ "Открытое письмо членов РАН по поводу ликвидации Российской академии наук. Letter of members of Russian Academy of Sciences". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Письма зарубежных ученых". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Putin Decree Shakes Up Russian Science Funding". Science. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

President Vladimir Putin last week signed a clutch of decrees that could have a profound effect on science in Russia. One stipulates that all state research funding should be distributed via a competitive grants system. Previously, research institutes received government support to cover things such as upkeep of buildings and utility bills, but that could now stop, as will the government's so-called state targeted programs, which single out certain areas for direct financial support.

- ^ Dobrovidova, Olga (30 March 2017). "Election chaos at Russian Academy of Sciences". Nature. 543 (7647): 601. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.21715. PMID 28358104. S2CID 157308395.

an election that was supposed to determine the new president of the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) was cancelled at the last minute. The three candidates—including incumbent president Vladimir Fortov—pulled out on 20 March, just two days before the election was scheduled to happen. Three days later, the Russian government appointed academy vice-president Valery Kozlov, who had not planned to stand in the election, as acting leader.

- ^ "Putin tightens control over Russian Academy of Sciences". Science. 27 June 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

The Russian government has taken further steps to tighten its grip on the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) in Moscow. On 23 June, the State Duma—one of the two chambers of the Russian parliament—passed the first draft of a new law that would give President Vladimir Putin the final say in the elections for RAS's presidency.

- ^ "Президент РАН заявил о завершении реформирования академии". ТАСС. Retrieved 2019-07-20.

- ^ "Putin splits Russia's Education Ministry and renames the Communications Ministry". Meduza. 2018-05-15. Retrieved 2018-05-17.

- ^ Allakhverdov, Andrey; Pokrovsky, Vladimir (18 May 2018). "Head of controversial agency becomes Russian minister for science and higher education". Science. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

In a major restructuring, the Russian government has decided to split its Ministry of Education and Science here into two new departments: the Ministry of Education, responsible for primary and secondary education, and a new, separate Ministry for Science and Higher Education. Heading the latter will be Mikhail Kotyukov, a former head of the controversial Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations (FASO), which until now managed property and real estate of research institutions within the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS), and effectively had control over the academy.

- ^ Liu Zhen (2023-07-02). "Russia opens research centre on Xi Jinping's ideology, the first outside China". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ^ "Президенты Российской академии наук за всю историю" ("Presidents of the Russian Academy of Sciences throughout its history") (in Russian) - at the Academy's official site.

- ^ Алексей Торгашев. "Академия наук, которой не было" [The Academy which wasn't]. freetowns.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on April 17, 2009.

- ^ a b Robert E. Bradley; Ed Sandifer, eds. (2007). Leonhard Euler: Life, Work and Legacy. Elsevier. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-08-047129-7.

- ^ "Орлов Владимир Григорьевич". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Douglas, Alfred (1971). How to Consult the I Ching, the Oracle of Change. Springer. p. 129. ISBN 978-3-7643-7539-3.

- ^ "Пушкинский Дом (ИРЛИ РАН) > Новости". Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Пушкинский Дом (ИРЛИ РАН) > Новости". Archived from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ O. Dobrovidova (27 March 2017). "Election chaos at Russian Academy of Sciences". Nature. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ Report of the mandate committee of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of the ninth convocation.

- ^ A. Pelt (2016-11-24). "Чем занимаются учёные в Госдуме" [What do scientists in the State Duma do]. Dni.ru. Archived from the original on 2018-01-17. Retrieved 2018-01-11.

Sources

[edit]- Calinger, Ronald (1996). "Leonhard Euler: The First St. Petersburg Years (1727–1741)". Historia Mathematica. 23 (2): 121–66. doi:10.1006/hmat.1996.0015.