Arghun

| Arghun | |

|---|---|

Arghun enthroned with his khatun (possibly Quthluq Khatun) in a painting c.1430. Bibliothèque nationale de France (Supplément persan 1113).[1] | |

| Il-Khan | |

| Reign | 11 August 1284 – 12 March 1291 |

| Confirmation by Kublai | 23 February 1286 |

| Predecessor | Tekuder |

| Successor | Gaykhatu |

| Born | 8 March 1258 Baylaqan |

| Died | March 10, 1291 (aged 33) Bāḡča, Arran |

| Burial | 12 March 1291 near Sojas |

| Spouse | Quthluq Khatun Uruk Khatun Todai Khatun Saljuk Khatun Bulughan Khatun Qutai Khatun Bulughan Khatun Qultak Agachi Argana Aghachi Oljatai Khatun |

| Issue | Ghazan Öljaitü |

| Dynasty | Borjigin |

| Father | Abaqa |

| Mother | Qaitmish Egec̆i |

| Religion | Buddhism |

Arghun Khan (Mongolian Cyrillic: Аргун; Traditional Mongolian: ᠠᠷᠭᠤᠨ; c. 1258 – 10 March 1291) was the fourth ruler of the Mongol empire's Ilkhanate division, from 1284 to 1291. He was the son of Abaqa Khan, and like his father, was a devout Buddhist (although pro-Christian). He was known for sending several emissaries to Europe in an unsuccessful attempt to form a Franco-Mongol alliance against the Muslim Mamluks in the Holy Land. It was also Arghun who requested a new bride from his great-uncle Kublai Khan. The mission to escort the young Kököchin across Asia to Arghun was reportedly entrusted to Marco Polo. Arghun died before Kököchin arrived, so she Arghun's son Ghazan married her instead.

Early life

[edit]Arghun was born to Abaqa Khan and Qaitmish Egec̆i (a concubine)[2] in 8 March[3] 1258 (although Rashid al-Din states it was in 1262, which is unlikely)[4] near Baylaqan. He grew up in Khorasan under care of Sartaq Noyan (from Jalair tribe) who was his military commander of encampment and Jochigan Noyan (from Bargut tribe) who was his atabeg. He commanded an army at the age of 20 against Negudaris. He left his father's encampment on 14 July 1279 for Seistan where he captured Öljai Buqa (son of Mubarakshah). After Abaqa's death in 1282, he was talked out of running against his uncle Ahmad Tekuder in the kurultai. Tekuder was duly chosen as sultan. He is also known as Sultan Ahmad.

Bid for the throne

[edit]

Tekuder's election brought Juvayni brothers to power, who were accused of charges of embezzlement before. However Arghun believed Juvayni brothers were responsible for his father's death by poisoning. He came to Baghdad to spend winter of 1282-1283 and restarted the investigation on embezzlement accusation which may have caused Ata Malik's stroke on 5 March 1283.[5][6] His hatred grew upon hearing rumors that Shams al-Din Juvayni sent someone to poison him. Another cause of friction was Tekuder's order of arrest of Malik Fakhr ud-Din, governor of Ray, whom Arghun appointed.

Tekuder on the other hand began to be suspicious of his half-brother Qonqurtai and Arghun's potential alliance. He sent military contingents commanded by Prince Jushkab, Uruq and Qurumushi (son of Hinduqur) to station in Diyar Bakr, so Qonqurtai and Arghun wouldn't be connected.[7] Qonqurtai was accused of conspiracy and was arrested by Tegüder's son-in-law, Alinaq - the viceroy of Georgia on 17 January 1284 and was executed next day. Another contingent of army was sent to Jazira, from where Gaykhatu and Baydu fled to Khorasan, to Arghun's encampment while several emirs such as Taghachar and Doladai were arrested.

Arghun started an open rebellion upon his return from Baghdad to Khorasan in 1283 to gain allegiance of minor nobles and amirs.[4] Tekuder's next step was to send Alinaq with 15.000 men against Arghun on 29 January, while ilkhan himself followed Alinaq on 26 April from his main army composed of Armenians and Georgians in addition to Mongols stationed in Mughan plain near Bilasuvar. Arghun prevailed on Alinaq in battle on 4 May south to Qazvin but nevertheless retreated to his lands in Khorasan. Ala ud-Daula Simnani, future Sufi saint of Kubrawiya order also fought in Arghun's army during this battle.[8] Arghun tried to make truce on halfway, which Ahmad against advices of his councillors, refused it. Another embassy sent by Arghun, this time led by his son Ghazan arrived at Tekuder's camp near Semnan on 31 May. Embassy was a success, as Ahmad accepted truce on condition if Arghun sends his brother Gaykhatu as a hostage. Arghun agreed to terms and sent his brother accompanied by two amirs, including Nawruz to custody of Buqa, then most senior of Tekuder's commanders on 13[9] or 28 June.[5] Buqa in turn handed over him to Ahmad who put Gaykhatu in Tödai Khatun's encampment. Despite this, Tekuder continued hostilities and kept advancing on Arghun. This made Buqa to harbor resentment towards Tekuder and grow more sympathetic to Arghun. On the other hand, he lost Tekuder's favor who started to invest his trust in Aq Buqa, another Jalair general.[10]

Seeing developments, Arghun sook refuge in Kalat-e Naderi, a strong fortress on 7 July with 100 men. But he was forced to surrender to Alinaq four days later. Victorious Tekuder left Arghun at Alinaq's captivity while himself left for Kalpush, where his main army was stationed. This was an opportunity Buqa was seeking - he broke into Alinaq's camp and set Arghun free, while killing Alinaq. Tekuder fled west and looted Buqa's encampment near Sultaniya in revenge. He continued on to his own pasturelands near Takht-i Suleyman on 17 July planning to escape to Golden Horde via Derbent. However, Qaraunas sent by Buqa soon caught up with him and arrested Tekuder. He was turned over to Arghun on 26 July on Ab-i Shur pasturelands, near Maragha.[5]

Reign

[edit]Arghun was informally enthroned on 11 August 1284 following Tekuder's execution.[11] A series of appointments came after coronation, as was custom - His cousins Jushkab (son of Jumghur) and Baydu were assigned to viceroyalty of Baghdad, Buqa's brother Aruq as his emir; while his brother Gaykhatu and uncle Hulachu were assigned to viceroyalty of Anatolia, Khorasan being assigned to his son Ghazan and his cousin Kingshu with Nawruz being their emir. Buqa, to whom he owed his throne was also awarded with dual office of sahib-i divan and amir al-umara, combining both military and civil administration on his hands.[12] Shams al-Din Juvayni was among the executed people as Arghun tried to avenge his father's supposed murder. The official approval by Kublai came only 23 February 1286, who not only confirmed Arghun's position as ilkhan, but also Buqa's new title - chingsang (Chinese: 丞相; lit. 'Chancellor'). Following this, Arghun had a second, this time official coronation ceremony on 7 April 1286.[4]

Fall of Buqa

[edit]Arghun saw the government as his own property[13] and didn't approve of Buqa and Aruq's arrogance and excesses, which soon raised them many enemies. Aruq practically ruled Baghdad as his own appanage, not paying taxes to central government, murdering his critics. Sayyid Imad ud-Din Alavi's murder on 30 December 1284 angered Buqa to the point summoning Abish Khatun herself to his court. It was Jalal ad-Din Arqan, one of her attendants first to reveal the details of murder, after which he[who?] was sawed in half. She was ordered to pay blood money worth 700.000 dinars to Sayyed's sons as the result of court. Other emirs, including Tuladai, Taghachar and Toghan started to conspire with Arghun to depose overpowered Buqa. His first step was to investigate former non-paid Salghurid taxes. As a result, he gained over 1.5 million dinars from Fars province. His next step came in 1287, when Buqa fell ill. He investigated Aruq in same fashion and started to control Baghdad's income as well, replacing him with Ordo Qiya. Another replacement came when Buqa's ally Amir Ali Tamghachi was removed from governorate of Tabriz.

Perceiving that he had lost the khan's favour, Buqa organized a conspiracy in Prince Jushkab and Arghun's vassal king Demetre II of Georgia (whose daughter Rusudan was married to Buqa's son) were implicated. Buqa promised Jushkab the throne on condition of appointment as naib of the empire upon success. However Jushkab sent news to Arghun about the treachery. Arghun in his turn sent his new emir Qoncuqbal to arrest Buqa. It's unknown how Rusudan escaped the purge by Arghun but Demetre II was summoned to capital and imprisoned as well. Buqa was put to death on January 16, 1289. He was succeeded as vizier by a Jewish physician, Sa’ad al-Daula of Abhar.[14] Sa'ad was effective in restoring order to the Ilkhanate's government, in part by aggressively denouncing the abuses of the Mongol military leaders.[15]

Reforms and purges

[edit]After dealing with Buqa, Arghun went for Hulaguid princes, whose loyalties were questionable - Jushkab was arrested and executed on 10 June 1289 while trying to raise an army. Hulachu and Yoshmut's son Qara Noqai were arrested on 30 May 1289, in connection with Nawruz's revolt in Khorasan. After a trial, they were sent to be executed in Damghan on 7 October 1290. After his relatives, Arghun authorizes Sa'd al-Dawla to execute children of Shams al-Din Juvayni and rest of his proteges.[16]

End of reign

[edit]According to Rashid al-Din, Arghun started to use opium after his visit to Maragha Observatory on 21 September 1289. After his second son Yesü Temür's death on 18 May 1290, he became rather disassociated from daily affairs of government. He founded the city of Arghuniyya in a suburb of Tabriz later in 1290[17] and a Buddhist temple in which he put statues resembling himself. Another city founded by him was Sharuyaz, which was completed during reign of his son Öljaitü.

Foreign relations

[edit]Relations with Golden Horde

[edit]As his predecessor, Arghun often clashed with Golden Horde. He repulsed a raiding party near Shamakhi on 5 May 1288. Another attack on Derbent occurred on 26 March 1289. Headed by Taghachar and other commanders, this attack too was prevented. War officially ended when Arghun returned to Bilasuvar on 2 May 1290.

Relations with Mamlukes

[edit]During Arghun's reign, the Egyptian Mamluks were continuously reinforcing their power in Syria. The Mamluk Sultan Qalawun recaptured Crusader territories, some of which, such as Tripoli, had been vassal states of the Il Khans. The Mamluks had captured the northern fortress of Margat in 1285, Lattakia in 1287, and completed the Fall of Tripoli in 1289.[18]

Relations with Christian powers

[edit]Arghun was one of a long line of Genghis-Khanite rulers who had endeavored to establish a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Europeans, against their common foes the Mamluks of Egypt. Arghun had promised his potential allies that if Jerusalem were to be conquered, he would have himself baptized. Yet by the late 13th century, Western Europe was no longer as interested in the crusading effort, and Arghun's missions were ultimately fruitless.[19]

First mission to the Pope

[edit]In 1285, Arghun sent an embassy and a letter to Pope Honorius IV, a Latin translation of which is preserved in the Vatican.[20][21] Arghun's letter mentioned the links that Arghun's family had to Christianity, and proposed a combined military conquest of Muslim lands:[22]

"As the land of the Muslims, that is, Syria and Egypt, is placed between us and you, we will encircle and strangle ("estrengebimus") it. We will send our messengers to ask you to send an army to Egypt, so that us on one side, and you on the other, we can, with good warriors, take it over. Let us know through secure messengers when you would like this to happen. We will chase the Saracens, with the help of the Lord, the Pope, and the Great Khan."

— Extract from the 1285 letter from Arghun to Honorius IV, Vatican[23]

Second mission, to Kings Philip and Edward

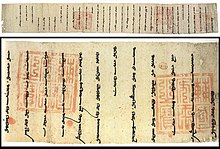

[edit]

Apparently left without an answer, Arghun sent another embassy to European rulers in 1287, headed by the Ongut Turk Nestorian monk from China Rabban Bar Sauma,[24] with the objective of contracting a military alliance to fight the Muslims in the Middle East, and take the city of Jerusalem.[20][25] The responses were positive but vague. Sauma returned in 1288 with positive letters from Pope Nicholas IV, Edward I of England, and Philip IV the Fair of France.[26]

Third mission

[edit]

In 1289, Arghun sent a third mission to Europe, in the person of Buscarel of Gisolfe, a Genoese who had settled in Persia. The objective of the mission was to determine at what date concerted Christian and Mongol efforts could start. Arghun committed to march his troops as soon as the Crusaders had disembarked at Saint-Jean-d'Acre. Buscarel was in Rome between July 15 and September 30, 1289, and in Paris in November–December 1289. He remitted a letter from Arghun to Philippe le Bel, answering to Philippe's own letter and promises, offering the city of Jerusalem as a potential prize, and attempting to fix the date of the offensive from the winter of 1290 to spring of 1291:[28]

"Under the power of the eternal sky, the message of the great king, Arghun, to the king of France..., said: I have accepted the word that you forwarded by the messengers under Saymer Sagura (Bar Sauma), saying that if the warriors of Il Khaan invade Egypt you would support them. We would also lend our support by going there at the end of the Tiger year’s winter [1290], worshiping the sky, and settle in Damascus in the early spring [1291].

If you send your warriors as promised and conquer Egypt, worshiping the sky, then I shall give you Jerusalem. If any of our warriors arrive later than arranged, all will be futile and no one will benefit. If you care to please give me your impressions, and I would also be very willing to accept any samples of French opulence that you care to burden your messengers with.

I send this to you by Myckeril and say: All will be known by the power of the sky and the greatness of kings. This letter was scribed on the sixth of the early summer in the year of the Ox at Ho’ndlon."

Buscarello was also bearing a memorandum explaining that the Mongol ruler would prepare all necessary supplies for the Crusaders, as well as 30,000 horses.[31] Buscarel then went to England to bring Arghun's message to King Edward I. He arrived in London January 5, 1290. Edward, whose answer has been preserved, answered enthusiastically to the project but remained evasive about its actual implementation, for which he deferred to the Pope.[32]

Assembly of a raiding naval force

[edit]In 1290, Arghun launched a shipbuilding program in Baghdad, with the intent of having war galleys which would harass the Mamluk commerce in the Red Sea. The Genoese sent a contingent of 800 carpenters and sailors, to help with the shipbuilding. A force of arbaletiers was also sent, but the enterprise apparently foundered when the Genoese government ultimately disowned the project, and an internal fight erupted at the Persian Gulf port of Basra among the Genoese (between the Guelph and Ghibelline factions).[31][33]

Fourth mission

[edit]Arghun sent a fourth mission to European courts in 1290, led by Andrew Zagan (or Chagan), who was accompanied by Buscarel of Gisolfe and a Christian named Sahadin.[34]

In 1291, Pope Nicholas IV proclaimed a new Crusade and negotiated agreements with Arghun, Hetoum II of Armenia, the Jacobites, the Ethiopians and the Georgians. On January 5, 1291, Nicholas addressed a vibrant prayer to all the Christians to save the Holy Land, and predicators started to rally Christians to follow Edward I in a Crusade.[35]

However, the efforts were too little and too late. On May 18, 1291, Saint-Jean-d'Acre was conquered by the Mamluks in the Siege of Acre.

In August 1291, Pope Nicholas wrote a letter to Arghun informing him of the plans of Edward I to go on a Crusade to recapture the Holy Land, stating that the Crusade could only be successful with the help of the "powerful arm" of the Mongols.[36] Nicholas repeated an oft-told theme of the Crusader communications to the Mongols, asking Arghun to receive baptism and to march against the Mamluks.[37] However Arghun himself had died on March 10, 1291, and Pope Nicholas IV would die in March 1292, putting an end to their attempts at combined action.[38]

Edward I sent an ambassador to Arghun's successor Gaikhatu in 1292 in the person of Geoffrey de Langley, but extensive contacts would only resume under Arghun's son Ghazan.

According to the 20th-century historian Runciman, "Had the Mongol alliance been achieved and honestly implemented by the West, the existence of Outremer would almost certainly have been prolonged. The Mamluks would have been crippled if not destroyed; and the Ilkhanate of Persia would have survived as a power friendly to the Christians and the West"[34]

Death

[edit]Arghun had developed a great interest in alchemy towards end of his reign. He gave shelters to Buddhist lamas who would advice him on religious matters. He also befriended a yogi who claimed to have lived longer than anyone and could offer Arghun the same. The way Rashid al-Din described this alchemist who gave a concoction of sulphur and mercury to Arghun[39] was the same substance that Marco Polo described as Indian yogis' experience.[40] After 8 months of taking the substance, Arghun fell ill. Tengriist shamans accused Toghachaq Khatun, Tekuder's widow among other women of witchcraft, who were executed on 19 January 1291 by being thrown into a river. Arghun's health deteriorated on 27 January and was paralyzed. Using opportunity, Taghachar and his allies made another purge with killing Sa'd al-Dawla and his proteges on 2 April. Arghun finally died on morning of March 7[41] or March 10,[42][4] 1291 in Arran. He was buried on a secret location in mountains of Sojas on 12 March.

Legacy

[edit]In the West, the 13th century saw such a vogue of Mongol things that many new-born children in Italy were named after Genghisid rulers, including Arghun: names such as Can Grande ("Great Khan"), Alaone (Hulagu), Argone (Arghun) or Cassano (Ghazan) are recorded with a high frequency.[43] According to the Dominican missionary Ricoldo of Montecroce, Arghun was "a man given to the worst of villainy, but for all that a friend of the Christians".[44] Arghun was a Buddhist, but as did most Turco-Mongols, he showed great tolerance for all faiths, even allowing Muslims to be judged under Islamic Law.

Arghun dynasty later claimed descent from him.[45] Hasan Fasai also claimed his treasure was found during reign of Qajar dynasty, trying to link Qajars to Qajar Noyan, son of his emir Sartaq Noyan.[46]

Family

[edit]Arghun had ten consorts, 7 of them being khatun and 3 of them being concubines. From his children, only 2 sons and 2 daughters reached to adulthood:

Principal wives:

- Qutlugh Khatun (d. 13 March 1288) — daughter of Tengiz Güregen of Oirats and Todogaj Khatun, daughter of Hulagu Khan

- Khitai-oghul (also named Sengirges, b. 3 March 1291[47] - d. 24 January 1298)

- Öljatai Khatun (m. 1288) — daughter of Sulamish, son of Tengiz Güregen and Todogaj Khatun, widow of Tengiz (they married in levirate)

- Uruk Khatun — daughter of Sarija, sister of emir Irinjin and a great-granddaughter of Ong Khan[48]

- Yesü Temür (born between 1271 and 1282, d. 18 May 1290)

- Öljaitü (b. 24 March 1282 - d. 16 December 1316)

- Öljatai Khatun — married firstly to Qunchuqbal, married secondly to Aq Buqa, married thirdly to her stepson, Amir Husayn Jalayir, son of Aq Buqa

- Öljai Timur — married firstly to Tukal, married secondly on 30 May 1296 to Qutlughshah

- Qutlugh Timur Khatun (died in youth in Baghdad)

- Seljuk Khatun (m. 1276, d. 1332, Niğde) — daughter of Rukn-ud-din Kilij Arslan IV, Seljuk Sultan of Rum[49]

- Bulughan Khatun Buzurg (d. 20 April 1286) — widow of Abaqa

- Bulughan Khatun Muazzama (m. 22 March 1290, d. 5 January 1310) — daughter of Otman, son of Abatai Noyan of Khongirad

- Dilenchi (died in infancy)

- Todai Khatun (m. 7 January 1287) — a lady from Khongirad, widow of Tekuder and previously Abaqa

Concubines:

- Kultak egechi (m. 1271) — daughter of Kihtar Bitigchi of Dörben

- Qutai — daughter of Qutlugh Buqa, son of Husayn Aqa

- Ergene egechi — previously concubine of Abaqa

See also

[edit]- Timeline of Buddhism (see 1285 CE)

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Consultation". archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr.

- ^ al-Din, Rashid (1999). Jami'u't-Tawarikh, Compendium of Chronicles: A History of the Mongols. Translated by Thackston, Wheeler M. Cambridge, MA: The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. p. 516.

- ^ Date was converted to Gregorian by Charles Melville. See: Melville, Charles (1994) - The Chinese-Uighur Animal Calendar in Persian Historiography of the Mongol Period

- ^ a b c d "ARḠŪN KHAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- ^ a b c Fisher 1968, pp. 364–368

- ^ "JOVAYNI, ʿALĀʾ-AL-DIN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- ^ Hamadani 1998, p. 551

- ^ Elias, Jamal J. (1995). The throne carrier of God : the life and thought of ʻAlāʼ ad-Dawla as-Simnānī. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 0-585-04596-8. OCLC 42628593.

- ^ Lane, George (3 May 2018). The Mongols in Iran : Qutb Al-Dīn Shīrāzī's Akhbār-i Moghulān. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-351-38752-1. OCLC 1035158115.

- ^ Wing, Patrick. (2016). Jalayirids. Edinburgh Univ Pr. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4744-0226-2. OCLC 948403225.

- ^ Hamadani 1998, p. 562

- ^ Hope 2016, p. 136

- ^ Hope 2016, p. 161

- ^ Fisher 1968, pp. 366–369

- ^ Mantran, Robert (Fossier, Robert, ed.) "A Turkish or Mongolian Islam" in The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250-1520, p. 298.

- ^ Hamadani 1998, p. 572

- ^ The Arts of Ornamental Geometry: A Persian Compendium on Similar and Complementary Interlocking Figures. A Volume Commemorating Alpay Özdural. BRILL. 2017-08-28. p. 169. ISBN 978-90-04-31520-4.

- ^ Tyerman, p. 817.

- ^ Prawdin, p. 372. "Argun revived the idea of an alliance with the West, and envoys from the Ilkhans once more visited European courts. He promised the Christians the Holy Land, and declared that as soon as they had conquered Jerusalem he would have himself baptised there. The Pope sent the envoys on to Philip the Fair of France and to Edward I of England. But the mission was fruitless. Western Europe was no longer interested in crusading adventures.

- ^ a b Runciman, p. 398.

- ^ "This Arghon loved the Christians very much, and several times asked to the Pope and the king of France how they could together destroy all the Sarazins" - Le Templier de Tyr - French original:"Cestu Argon ama mout les crestiens et plusors fois manda au pape et au roy de France trayter coment yaus et luy puissent de tout les Sarazins destruire" Guillame de Tyr (William of Tyre) "Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum" #591

- ^ The Crusades Through Arab Eyes p. 254: Arghun, grandon of Hulagu, "had resurrected the most cherished dream of his predecessors: to form an alliance with the Occidentals and thus to trap the Mamluk sultanate in a pincer movement. Regular contacts were established between Tabriz and Rome with a view to organizing a joint expedition, or at least a concerted one."

- ^ Quote in "Histoires des Croisades III", Rene Grousset, p. 700.

- ^ Morris Rossabi (28 November 2014). From Yuan to Modern China and Mongolia: The Writings of Morris Rossabi. BRILL. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-90-04-28529-3.

- ^ Rossabi, p. 99.

- ^ Boyle, in Camb. Hist. Iran V, pp. 370–71; Budge, pp. 165–97. Source Archived 2008-04-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Grands Documents de l'Histoire de France, Archives Nationales de France, p. 38, 2007.

- ^ Runciman, p. 401.

- ^ Alternative translation of Arghun's letter[dead link]

- ^ For another translation here Archived 2020-08-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Jean Richard, p. 468.

- ^ "Histoire des Croisades III", p. 713, Rene Grousset.

- ^ "Only a contingent of 800 Genoese arrived, whom he (Arghun) employed in 1290 in building shipd at Baghdad, with a view to harassing Egyptian commerce at the southern approaches to the Red Sea", p. 169, Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West

- ^ a b Runciman, p. 402.

- ^ Dailliez, pp. 324–325.

- ^ Schein, p. 809.

- ^ Jackson, p. 169.

- ^ Runciman, p. 412.

- ^ Hamadani 1998, p. 574

- ^ Polo, Marco (2018-03-01). Travels of Marco Polo. B&R Samizdat Express. ISBN 978-1-4554-1591-5.

- ^ "He died on March 7, 1291." Steppes, p. 376.

- ^ Hamadani 1998, p. 575

- ^ Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, p. 315.

- ^ Jackson, p. 176.

- ^ Qazi, Muhammad Naeem (2010). TARKHAN DYNASTY AT MAKLI HILL, THATTA (PAKISTAN): HISTORY AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE SELECTED MONUMENTS (Thesis thesis). UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR.

- ^ Hope 2016, p. 8

- ^ Ta'rīkh-i Shaikh Uwais : (History of Shaikh Uais) : Am important source for the history of Adharbaijān in the fourteenth century. p. 43.

- ^ Howorth, Sir Henry Hoyle (1888). History of the Mongols, from the 9th to the 19th Century, Volume 3. Burt Franklin. p. 354. ISBN 978-1296812676.

- ^ Lambton, Ann K. S. (January 1, 1988). Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia. SUNY Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-887-06133-2.

- ^ Lambton, Ann K. S. (January 1, 1988). Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia. SUNY Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-887-06133-2.

References

[edit]- Le Templier de Tyr (c. 1300), Online (Original French).

- "The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China", Sir E. A. Wallis Budge. Online

- Dailliez, Laurent (1972). Les Templiers (in French). Editions Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02006-X.

- Fisher, W. B. (1968), The Cambridge History of Iran, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-06935-1

- Foltz, Richard, Religions of the Silk Road, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- Grousset, René (1935). Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291 (in French). Editions Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02569-X.

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia, Naomi Walford, (tr.), New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1970.

- Hamadani, Rashidaddin (1998), Compendium of Chronicles, vol. 3, translated by Thackston, W.M., Harvard University, Dept. of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, OCLC 41120851

- Hope, Michael (2016), Power, Politics, and Tradition in the Mongol Empire and the Ilkhanate of Iran, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198768593.001.0001, ISBN 9780198768593

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-36896-5.

- Lebédel, Claude (2006). Les Croisades, origines et conséquences (in French). Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 2-7373-4136-1.

- Maalouf, Amin (1984). The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 0-8052-0898-4.

- Prawdin, Michael (1961) [1940]. Mongol Empire. Collier-Macmillan Canada. ISBN 1-4128-0519-8.

- Richard, Jean (1996). Histoire des Croisades. Fayard. ISBN 2-213-59787-1.

- Rossabi, Morris (1992). Voyager from Xanadu: Rabban Sauma and the first journey from China to the West. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 4-7700-1650-6.

- Runciman, Steven (1987) [1952–1954]. A history of the Crusades 3. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013705-7.

- Schein, Sylvia (October 1979). "Gesta Dei per Mongolos 1300. The Genesis of a Non-Event". The English Historical Review. 94 (373): 805–819. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCIV.CCCLXXIII.805. JSTOR 565554.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02387-0.