Namárië

"Namárië" (pronounced [na.ˈmaː.ri.ɛ]) is a poem by J. R. R. Tolkien written in one of his constructed languages, Quenya, and published in The Lord of the Rings.[T 1] It is subtitled "Galadriel's Lament in Lórien", which in Quenya is Altariello nainië Lóriendessë. The poem appears, too, in a book of musical settings by Donald Swann of songs from Middle-earth, The Road Goes Ever On; the Gregorian plainsong-like melody was hummed to Swann by Tolkien. The poem is the longest Quenya text in The Lord of the Rings and also one of the longest continuous texts in Quenya that Tolkien ever wrote. An English translation is provided in the book.

"Namárië" has been set to music by The Tolkien Ensemble, by the Finnish composer Toni Edelmann for a theatre production, and by the Spanish band Narsilion. Part of the poem is sung by a female chorus in a scene of Peter Jackson's The Fellowship of the Ring to music by Howard Shore.

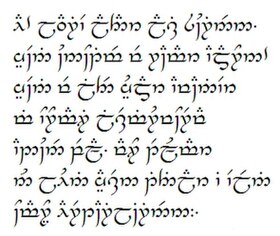

Poem

[edit]The poem names Valimar, the residence of the Valar and the Vanyar Elves; the Calacirya, the gap in the Pelori Mountains that lets the light of the Two Trees stream out across the sea to Middle-earth; and Oiolossë ("Ever-white") or Taniquetil, the holy mountain,[1] the tallest of the Pelori Mountains; the Valar Manwë and his spouse Varda, to whom the poem is addressed, lived on its summit.[T 2]

The poem starts and ends as follows:

| Quenya: Part of Namárië Altariello nainië Lóriendessë |

Translation: "Farewell" "Galadriel's Lament in Lórien" |

|---|---|

Ai! laurië lantar lassi súrinen, |

Ah! like gold fall the leaves in the wind, |

Tolkien provided a guide to how to pronounce and intone the poem in the book of his songs, The Road Goes Ever On, which contains a setting of the poem to music, and an audio recording, by Donald Swann. The text there is accompanied by "a literal translation", on which Tolkien comments that the version in The Fellowship of the Ring is "sufficiently accurate".[T 3]

Settings

[edit]Donald Swann

[edit]

Namárië was set to music by Donald Swann with Tolkien's help: Swann proposed a setting, but Tolkien replied that he had a different setting in mind, and hummed a Gregorian chant. Swann took this up, feeling that it worked perfectly with the poem, commenting:[2]

In the following week I played it over many times to the Elvish words. There was no doubt that this monodic line from an early church tradition expressed the words ideally, not only the sadness of the word "Namárië", and the interjection "Ai!", but equally the ritual mood of the Elves.[2]

The sheet music and an audio recording are in their 1967 book The Road Goes Ever On. The setting is in the key of A major and in 4

4 time.[3] A separate recording survives of Tolkien singing the poem to a Gregorian chant.[4] Gill Gleeson, writing in Mallorn, states that it has the quality of an "improvisatory plainsong for voice and (melodic) instrument, a self-contained unharmonised melody."[5] She describes it as "finely balanced in proportion, and held in tension between two modal scales", with the reciting-note C# as a "pivot". She likens the instrumental mode to a "descending melodic minor scale" in F#, with the vocal mode in A major.[5]

The Tolkien Ensemble

[edit]

Between 1997 and 2005, the Danish Tolkien Ensemble published four CDs featuring every poem from The Lord of the Rings. The recordings included two versions of "Namárië", both composed by the ensemble leader Caspar Reiff. They are both on the album An Evening in Rivendell, sung by the Danish Mezzo-soprano Signe Asmussen. One sets the original Quenya text to music; the other features the English translation.[6]

Howard Shore

[edit]In his music for The Lord of the Rings film series, composed between 2000 and 2004 to support Peter Jackson's film trilogy, Howard Shore made use of part of Namárië. The scene "The Fighting Uruk-hai" is accompanied, non-diegetically, by a female chorus singing the poem in Quenya, over images of the Elf-lady Galadriel gazing at the remaining eight members of the Fellowship of the Ring as they leave Lothlórien.[7]

Other composers

[edit]In 2001, the Finnish composer Toni Edelmann wrote a setting of the poem for the musical Sagan om Ringen ("The Lord of the Rings") at the Swedish Theatre, Helsinki.[8][9][10] In 2008, the Spanish neoclassical dark wave band Narsilion published a studio album called Namárië. Among other Tolkien-inspired songs it features a track Namárië: El Llanto de Galadriel ("Namárië: Galadriel's Lament").[11] Kogaionon magazine called it a mature and complex album "with a medieval and ... forceful aura".[12]

Analysis

[edit]As the longest text in the Elvish language Quenya that Tolkien provided in The Lord of the Rings or elsewhere,[13] Namárië has attracted the attention of linguists. Helge Fauskanger has made a word-by-word analysis of the text, noting that the version in The Road Goes Ever On is "nearly" identical to that in the novel: Tolkien added accent marks to indicate stronger and weaker stresses to guide the singer.[1] Fauskanger describes the language used in the poem as the "Late Exilic" or "Third Age" variant of Quenya.[14] Fauskanger comments that while "Valimar", named in the poem, normally denotes the city of the Valar, the poem uses it to mean the whole of Valinor, the blessed realm.[1] Allan Turner states that Tolkien meant the poem to embody the Elvish culture from the deep past that Galadriel remembers.[15] The poem does not rhyme or scan conventionally; Jonathan McColl, writing in Mallorn, comments that while he prefers poems which use those devices, he finds "even ... the translation" of Namárië poetic, while the original Quenya with its Gregorian setting is "lovely".[16][a]

The Quenya word namárië is a reduced form of á na márië, meaning literally "be well", an Elvish formula used for greeting and for farewell.[T 4] The earliest version of the poem was published posthumously in The Treason of Isengard. Tolkien did not provide a translation of that version, and some of the words used differ in form from those in the version that appeared in The Lord of the Rings.[T 5]

Adaptations

[edit]The band Led Zeppelin adapted the first line of "Namárië" for the opening of their 1969 song "Ramble On" on their studio album Led Zeppelin II. The English line "Leaves are falling all around" represents Tolkien's "Ah! like gold fall the leaves in the wind". Further references to Tolkien's writing appear in the rest of the song, which mentions Gollum and Mordor.[19]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey, discussing other poems in The Lord of the Rings, writes that Tolkien uses multiple poetic devices, including internal half-rhyme, alliteration, and alliterative assonance.[17] Further, he states of another Elvish poem, A Elbereth Gilthoniel, that Tolkien "believed that untranslated elvish would do a job that English could not".[18] Shippey calls the usage "idiosyncratic and daring",[18] and suggests that readers take something important from a song in another language, namely the feeling or style that it conveys, even if "it escapes a cerebral focus".[18]

References

[edit]Primary

[edit]- ^ Tolkien 1954a, Book 2, ch. 8 "Farewell to Lórien"

- ^ Tolkien 1977, "Valaquenta"

- ^ Tolkien & Swann 2002, pp. 65–70

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R., "Parma Eldalamberon", 17, p. 162.

- ^ Tolkien 1989, pp. 284–285

Secondary

[edit]- ^ a b c Fauskanger, Helge. "Namárië: Word-by-word Analysis". Ardalambion. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ a b c Tolkien & Swann 2002, pp. v–vi, Foreword by Donald Swann

- ^ Tolkien & Swann 2002, pp. 22–24 (sheet music), with CD inside rear cover.

- ^ Hargrove, Gene (January 1995). "Music in Middle-earth". University of North Texas.

- ^ a b Gleeson, Gill (1981). "Music in Middle-earth". Mallorn (16): 29–31.

- ^ "List of tracks by the Tolkien Ensemble". The Tolkien Ensemble. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Adams 2010, pp. 189–192.

- ^ "'Namárië': The most spectacular version of the farewell song written by Tolkien". Counting Stars. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Saarinen, Pale (14 October 2013). "Toni Edelmannille Musiikki on Kutsumus" [For Toni Edelmann, Music is a Calling] (in Finnish). Retrieved 19 January 2023.

Edelmann's latest great love has been Tolkien's classic The Lord of the Rings, which since January has been performed at Svenska Teatter to full halls with the backing band, four musicians and the young conductor-arranger Lauri Järvilehto.

- ^ "Discography: Toni Edelmann (Finland) - Theatrical production scores". Tolkien Music. 22 December 2022. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

Sagan om Ringen (n/r 2001) [Svenska Teatern] Lorien Namarie

- ^ Narsilion – Namárië (CD). Gravitator Records. 2008. GRR 095.

- ^ "Narsilion 'Namarie' CD '07 (Black Rain)". Kogaionon Magazine (10). 14 December 2010.

- ^ Pesch, Helmut W. (2003). Elbisch [Elvish] (in German). Bastei Lübbe. p. 25. ISBN 3-404-20476-X.

- ^ Fauskanger, Helge. "Introduction". Ardalambion. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Turner, Allan (2011) [2005]. Translating Tolkien: Philological Elements in The Lord of the Rings. Frankfurt: Peter Lang Publishing. p. 156. ISBN 978-3-6530-1058-9.

- ^ McColl, Jonathan (1977). "Tolkien the Rhymer". Mallorn (11): 40–43.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 217–221.

- ^ a b c Shippey 2001, pp. 127–133.

- ^ Meyer, Stephen C.; Yri, Kirsten (2020). The Oxford Handbook of Music and Medievalism. Oxford University Press. p. 732. ISBN 978-0-19-065844-1.

Sources

[edit]- Adams, Doug (2010). The Music of The Lord of the Rings Films. Éditions Didier Carpentier. ISBN 978-0-7390-7157-1.

- Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261104013.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-261-10275-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R.; Swann, Donald (2002) [1968]. The Road Goes Ever On (3rd ed.). London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-713655-1.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1989). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Treason of Isengard. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-51562-4.