Grateful Dead

Grateful Dead | |

|---|---|

A promotional photo of Grateful Dead in 1970. Left to right: Bill Kreutzmann, Ron McKernan, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, Mickey Hart, and Phil Lesh. | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | The Warlocks |

| Origin | Palo Alto, California, U.S. |

| Genres | Rock |

| Discography | Grateful Dead discography |

| Years active | 1965–1995 |

| Labels | |

| Spinoffs |

|

| Past members | |

| Website | dead |

The Grateful Dead was an American rock band formed in Palo Alto, California in 1965.[1][2] Known for their eclectic style that fused elements of rock, blues, jazz, folk, country, bluegrass, rock and roll, gospel, reggae, and world music with psychedelia,[3][4] the band is famous for improvisation during their live performances,[5][6] and for their devoted fan base, known as "Deadheads". According to the musician and writer Lenny Kaye, the music of the Grateful Dead "touches on ground that most other groups don't even know exists."[7] For the range of their influences and the structure of their live performances, the Grateful Dead are considered "the pioneering godfathers of the jam band world".[8]

The Grateful Dead was founded in the San Francisco Bay Area during the rise of the counterculture of the 1960s.[9][10][11][12] The band's founding members were Jerry Garcia (lead guitar and vocals), Bob Weir (rhythm guitar and vocals), Ron "Pigpen" McKernan (keyboards, harmonica, and vocals), Phil Lesh (bass guitar and vocals), and Bill Kreutzmann (drums).[13] Members of the Grateful Dead, originally known as the Warlocks, had played together in various Bay Area ensembles, including the traditional jug band Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions. Lesh was the last member to join the Warlocks before they changed their name to Grateful Dead, replacing Dana Morgan Jr., who had played bass for a few gigs. Drummer Mickey Hart and non-performing lyricist Robert Hunter joined in 1967. With the exception of McKernan, who died in 1973, and Hart, who left the band from 1971 to 1974, the core of the band stayed together for its entire 30-year history.[14] Other official members of the band included Tom Constanten (keyboards from 1968 to 1970), John Perry Barlow (non-performing lyricist from 1971 to 1995),[15] Keith Godchaux (keyboards and occasional vocals from 1971 to 1979), Donna Godchaux (vocals from 1972 to 1979), Brent Mydland (keyboards and vocals from 1979 to 1990), and Vince Welnick (keyboards and vocals from 1990 to 1995).[16] Bruce Hornsby (accordion, piano, vocals) was a touring member from 1990 to 1992, as well as a guest with the band on occasion before and after the tours.

After Garcia's death in 1995, former members of the band, along with other musicians, toured as The Other Ones in 1998, 2000, and 2002, and as The Dead in 2003, 2004, and 2009. In 2015, the four surviving core members marked the band's 50th anniversary in a series of concerts in Santa Clara, California, and Chicago that were billed as their last performances together.[17] There have also been several spin-offs featuring one or more core members, such as Dead & Company, Furthur, the Rhythm Devils, Phil Lesh and Friends, RatDog, and Billy & the Kids.

Despite having only one Top-40 single in their 30-year career, "Touch of Grey" (1987), the Grateful Dead remained among the highest-grossing American touring acts for decades. They gained a committed fanbase by word of mouth and through the free exchange of their live recordings, encouraged by the band's allowance of taping. In 2024, they broke the record for most Top-40 albums on the Billboard 200 chart.[18] Rolling Stone ranked the Grateful Dead number 57 on its 2011 list of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time".[19] The band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994,[20] and a recording of their May 8, 1977 performance at Cornell University's Barton Hall was added to the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress in 2012 for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[21] In 2024, Weir, Lesh, Kreutzmann, and Hart were recognized as part of the Kennedy Center Honors.[22]

Formation (1965–1966)

[edit]

The Grateful Dead began their career as the Warlocks, a group formed in early 1965 from the remnants of a Palo Alto, California jug band called Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions and members of The Wildwood Boys (Jerry Garcia, Ron "Pigpen" McKernan, David Nelson, Robert Hunter, and Norm Van Maastricht).[23] As The Wildwood Boys they played regularly at The Tangent, a folk music coffeehouse operated by Stanford Medical Center doctors Stuart "Stu" Goldstein and David "Dave" Shoenstadt on University Avenue in Palo Alto (1963).[24] As the Warlocks, the band's first show was at Magoo's Pizza Parlor, at 639 Santa Cruz Avenue in suburban Menlo Park, on May 5, 1965, now a Harvest furniture store. The band continued playing bar shows,[25] like Frenchy's Bikini-A-Go-Go[26][27] in Hayward and, importantly, five sets a night, five nights a week, for six weeks, at the In Room[28][29] in Belmont as the Warlocks,[30] but quickly changed the band's name after finding out that a different band known as the Warlocks had put out a record under that name. (The Velvet Underground also had to change its name from the Warlocks.)[31]

The name "Grateful Dead" was chosen from a dictionary. According to Lesh, Garcia "picked up an old Britannica World Language Dictionary ... [and] ... In that silvery elf-voice he said to me, 'Hey, man, how about the Grateful Dead?'"[32] The definition there was "the soul of a dead person, or his angel, showing gratitude to someone who, as an act of charity, arranged their burial." According to Alan Trist, director of the Grateful Dead's music publisher company Ice Nine, Garcia found the name in the Funk & Wagnalls Folklore Dictionary, when his finger landed on that phrase while playing a game of Fictionary.[33] In the Garcia biography Captain Trips, author Sandy Troy states that the band was smoking the psychedelic DMT at the time.[34] The motif of the "grateful dead" appears in folktales from a variety of cultures.[35]

The first show under the name Grateful Dead was in San Jose on December 4, 1965, at one of Ken Kesey's Acid Tests.[36][37][38] Scholar Michael Kaler has written that the Dead's participation in the Acid Tests was crucial both to the development of their improvisational vocabulary and to their bonding as a band, with the group having set out to foster an intra-band musical telepathy.[39] Kaler has further pointed out that the Dead's pursuit of a new improvisatory rock language in 1965 chronologically coincided with that same goal's adoption by Jefferson Airplane, Pink Floyd and the Velvet Underground.[40]

Earlier demo tapes have survived, but the first of over 2,000 concerts known to have been recorded by the band's fans was a show at the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco on January 8, 1966.[41] Later that month, the Grateful Dead played at the Trips Festival, a three-day psychedelic rock weekend party and event produced by Ken Kesey, Stewart Brand, and Ramon Sender, that, in conjunction with the Merry Pranksters, brought the nascent hippie movement together for the first time.[42][43]

Other supporting personnel who joined early included Rock Scully, who heard of the band from Kesey and signed on as manager after meeting them at the Big Beat Acid Test; Stewart Brand, "with his side show of taped music and slides of Indian life, a multimedia presentation" at the Big Beat and then, expanded, at the Trips Festival; and Owsley Stanley, the "Acid King" whose LSD supplied the Acid Tests and who, in early 1966, became the band's financial backer, renting them a house on the fringes of Watts, Los Angeles, and buying them sound equipment. "We were living solely off of Owsley's good graces at that time. ... [His] trip was he wanted to design equipment for us, and we were going to have to be in sort of a lab situation for him to do it", said Garcia.[34]

Main career (1967–1995)

[edit]Pigpen era (1967–1972)

[edit]

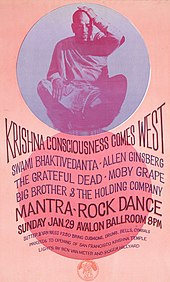

One of the group's earliest major performances in 1967 was the Mantra-Rock Dance, a musical event held on January 29, 1967, at the Avalon Ballroom by the San Francisco Hare Krishna temple. The Grateful Dead performed at the event along with the Hare Krishna founder Bhaktivedanta Swami, poet Allen Ginsberg, bands Moby Grape and Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin, donating proceeds to the temple.[44][45] The band's first LP, The Grateful Dead, was released on Warner Brothers in 1967.

On May 3, 1968, the band played a free concert at Columbia University during the anti–Vietnam War student protests during which students occupied several campus buildings. In order to play, the band, equipment and all, had to be “smuggled” on campus in the back of a bread delivery truck. “We were already jamming away before the security and police could stop us.”[46]

Classically trained trumpeter Phil Lesh performed on bass guitar. Bob Weir, the youngest original member of the group, played rhythm guitar. Ron "Pigpen" McKernan played keyboards, percussion, and harmonica until shortly before his death in 1973 at the age of 27. Garcia, Weir, and McKernan shared the lead vocal duties more or less equally; Lesh sang only a few leads, but his tenor was a key part of the band's three-part vocal harmonies. Bill Kreutzmann played drums, and in September 1967 was joined by a second drummer, New York City native Mickey Hart, who also played a wide variety of other percussion instruments.

1970 included tour dates in New Orleans, where the band performed at The Warehouse for two nights. On January 31, 1970, the local police raided their hotel on Bourbon Street and arrested and charged 19 people with possession of various drugs.[47] The second night's concert was performed as scheduled after bail was posted. Eventually, the charges were dismissed, except those against sound engineer Owsley Stanley, who was already facing charges in California for manufacturing LSD. This event was later memorialized in the lyrics of “Truckin'", a single from American Beauty that reached number 64 on the charts.

Hart took time off from the band in February 1971, after his father, an accountant, absconded with much of the band's money;[48] Kreutzmann was once again as the sole percussionist. Hart rejoined the Grateful Dead for good in October 1974. Tom "TC" Constanten was added as a second keyboardist from 1968 to 1970, to help Pigpen keep up with an increasingly psychedelic sound, while Pigpen transitioned into playing various percussion instruments and vocals.

After Constanten's departure, Pigpen reclaimed his position as sole keyboardist. Less than two years later, in late 1971, Pigpen was joined by another keyboardist, Keith Godchaux, who played grand piano alongside Pigpen's Hammond B-3 organ. In early 1972, Keith's wife, Donna Jean Godchaux, joined the Grateful Dead as a backing vocalist.

Following the Grateful Dead's "Europe '72" tour, Pigpen's health had deteriorated to the point that he could no longer tour with the band. His final concert appearance was June 17, 1972, at the Hollywood Bowl, in Los Angeles;[49][50] he died on March 8, 1973, of complications from liver damage.[51]

Godchaux era (1972–1979)

[edit]

Pigpen's death did not slow down the Grateful Dead. With the help of manager Ron Rakow, the band soon formed its own record label, Grateful Dead Records.[52] Later that year, it released its next studio album, the jazz-influenced Wake of the Flood, which became their biggest commercial success thus far.[53] Meanwhile, capitalizing on the album's success, the band soon went back to the studio, and in June 1974 released another album, From the Mars Hotel. Not long after, the Dead decided to take a hiatus from live touring. The band travelled to Europe for a string of shows in September 1974, before performing a series of five concerts at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco in October 1974, and delved into various other projects.[54] The Winterland concerts were filmed, and Garcia compiled the footage into The Grateful Dead Movie, a feature-length concert film released in 1977.[55]

In September 1975, the Dead released their eighth studio album, Blues for Allah. The band resumed touring in June 1976, playing multiple dates in small theaters, rather than the stadium shows that had become common, and had exhausted them, in 1974.[52] That same year, they signed with Arista Records, and the new contract produced Terrapin Station in July 1977. The band's tour in the spring of that year is held in high regard by its fans, and its concert of May 8 at Cornell University is often considered one of the best performances of its career.[56][57][58] Their September 1977 concert at Raceway Park in Old Bridge Township, New Jersey was attended by 107,019 people and held the record for largest-ticketed concert in the United States by a single act for 47 years.[59]

Keith and Donna Jean Godchaux left the band in February 1979, citing artistic differences.

Mydland/Welnick era (1979–1995)

[edit]

Following the Godchauxs' departure, Brent Mydland joined as keyboardist and vocalist and was considered "the perfect fit." The Godchauxs then formed the Heart of Gold Band, before Keith died in a car accident in July 1980. Mydland was the keyboardist for the Grateful Dead for 11 years until his death by narcotics overdose in July 1990,[60] becoming the third keyboardist to die.

Shortly after Mydland found his place in the early 1980s, Garcia's health began to decline. He became a frequent smoker of "Persian," a type of heroin, and he gained weight at a rapid pace. He lost his liveliness on stage, his voice was strained, and Deadheads worried for his health. After he began to curtail his opiate usage gradually in 1985, Garcia slipped into a diabetic coma for several days in July 1986, leading to the cancelation of all concerts in the fall of that year. Garcia recovered, the band released In the Dark in July 1987, which became its best-selling studio album and produced its only top-40 single, "Touch of Grey," Also, that year, the group toured with Bob Dylan, as heard on the album Dylan & the Dead.

Mydland died in July 1990 and Vince Welnick, former keyboardist for the Tubes, joined as a band member, while Bruce Hornsby, who had a successful career with his band the Range, joined temporarily as a bridge to help Welnick learn songs. Both performed on keyboards and vocals—Welnick until the band's end, and Hornsby mainly from 1990 to 1992.

Saxophonist Branford Marsalis played five concerts with the band between 1990 and 1994.[61]

The Grateful Dead performed its final concert on July 9, 1995, at Soldier Field in Chicago.[62]

Aftermath (1995–present)

[edit]

Jerry Garcia died on August 9, 1995. A few months after Garcia's death, the remaining members of the Grateful Dead decided to disband.[63] Since that time, there have been a number of reunions by the surviving members involving various combinations of musicians. Additionally, the former members have also begun or continued individual projects.

In 1998, Bob Weir, Phil Lesh, and Mickey Hart, along with several other musicians, formed a band called the Other Ones, and performed a number of concerts that year, releasing a live album, The Strange Remain, the following year. In 2000, the Other Ones toured again, this time with Kreutzmann but without Lesh. After taking another year off, the band toured again in 2002 with Lesh. That year, the Other Ones then included all four living former Grateful Dead members who had been in the band for most or all of its history. At different times the shifting lineup of the Other Ones also included guitarists Mark Karan, Steve Kimock, and Jimmy Herring, keyboardists Bruce Hornsby, Jeff Chimenti, and Rob Barraco, saxophonist Dave Ellis, drummer John Molo, bassist Alphonso Johnson, and vocalist Susan Tedeschi.[64]

In 2003, the Other Ones, still including Weir, Lesh, Hart, and Kreutzmann, changed their name to the Dead.[65] The Dead toured the United States in 2003, 2004 and 2009. The band's lineups included Jimmy Herring and Warren Haynes on guitar, Jeff Chimenti and Rob Barraco on keyboards, and Joan Osborne on vocals.[66] In 2008, members of the Dead played two concerts, called "Deadheads for Obama" and "Change Rocks".

Following the 2009 Dead tour, Lesh and Weir formed the band Furthur, which debuted in September 2009.[67] Joining Lesh and Weir in Furthur were Chimenti (keyboards), John Kadlecik (guitar), Joe Russo (drums), Jay Lane (drums), Sunshine Becker (vocals), and Zoe Ellis (vocals). Lane and Ellis left the band in 2010, and vocalist Jeff Pehrson joined later that year. Furthur disbanded in 2014.[68]

In 2010, Hart and Kreutzmann re-formed the Rhythm Devils, and played a summer concert tour.[69] In the fall of 2015, Hart, Kreutzmann and Weir teamed up with Chimenti, guitarist John Mayer, and bassist Oteil Burbridge to form a band called Dead & Company. Mayer recounted that in 2011 he was listening to Pandora and happened upon the Grateful Dead song "Althea", and that soon Grateful Dead music was all he would listen to.[70] Dead & Company toured every year (except 2020), until announcing that their summer 2023 tour, which saw Kreutzmann replaced by Lane, would be their last.[71] However, they later clarified that it was only their last tour, and they continue to perform concerts.

Since 1995, the former members of the Grateful Dead have also pursued solo music careers. Both Bob Weir & RatDog[72][73] and Phil Lesh and Friends[74][75] have performed many concerts and released several albums. Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann have also each released a few albums. Hart has toured with his world music percussion ensemble Planet Drum[76] as well as the Mickey Hart Band.[77] Kreutzmann has led several different bands, including BK3,[78] 7 Walkers (with Papa Mali),[79] and Billy & the Kids.[80] Donna Godchaux has returned to the music scene, with the Donna Jean Godchaux Band,[81] and Tom Constanten also continues to write and perform music.[82] All of these groups continue to play Grateful Dead music.

In October 2014, it was announced that Martin Scorsese would produce a documentary film about the Grateful Dead, to be directed by Amir Bar-Lev. David Lemieux supervised the musical selection, and Weir, Hart, Kreutzmann, and Lesh agreed to new interviews for the film.[83] Bar-Lev's four-hour documentary, titled Long Strange Trip, was released in 2017.[84][85]

Barlow died in 2018[86] and Hunter in 2019.[87] Lesh died in 2024.[88]

"Fare Thee Well"

[edit]In 2015, Weir, Lesh, Kreutzmann, and Hart reunited for five concerts called "Fare Thee Well: Celebrating 50 Years of the Grateful Dead".[89] The shows were performed on June 27 and 28 at Levi's Stadium in Santa Clara, California, and on July 3, 4 and 5 at Soldier Field in Chicago.[89][90] The band stated that this would be the final time that Weir, Lesh, Hart, and Kreutzmann would perform together.[91] They were joined by Trey Anastasio of Phish on guitar, Jeff Chimenti on keyboards, and Bruce Hornsby on piano.[92][93] Demand for tickets was very high.[94][95] The concerts were simulcast via various media.[96][97] The Chicago shows have been released as a box set of CDs and DVDs.[98]

Musical style

[edit]

The Grateful Dead formed during the era when bands such as the Beatles, the Beach Boys and the Rolling Stones were dominating the airwaves. "The Beatles were why we turned from a jug band into a rock 'n' roll band", said Bob Weir. "What we saw them doing was impossibly attractive. I couldn't think of anything else more worth doing."[99] Former folk-scene star Bob Dylan had recently put out a couple of records featuring electric instrumentation. Grateful Dead members have said that it was after attending a concert by the touring New York City band the Lovin' Spoonful that they decided to "go electric" and look for a "dirtier" sound. Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir (both of whom had been immersed in the American folk music revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s), were open-minded about the use of electric guitars.

The Grateful Dead's early music (in the mid-1960s) was part of the process of establishing what "psychedelic music" was, but theirs was essentially a "street party" form of it. They developed their "psychedelic" playing as a result of meeting Ken Kesey in Palo Alto, California, and subsequently becoming the house band for the Acid Tests he staged.[100] They did not fit their music to an established category such as pop rock, blues, folk rock, or country & western. Individual tunes within their repertoire could be identified under one of these stylistic labels, but overall their music drew on all of these genres and, more frequently, melded several of them. Bill Graham said of the Grateful Dead, "They're not the best at what they do, they're the only ones that do what they do."[101] Academics Paul Hegarty and Martin Halliwell argued that the Grateful Dead were "not merely as precursors of prog but as essential developments of progressiveness in its early days".[102] Often (both in performance and on recording) the Dead left room for exploratory, spacey soundscapes.

Their live shows, fed by an improvisational approach to music, were different from most touring bands. While rock and roll bands often rehearse a standard set, played with minor variations, the Grateful Dead did not prepare in this way. Garcia stated in a 1966 interview, "We don't make up our sets beforehand. We'd rather work off the tops of our heads than off a piece of paper."[103] They maintained this approach throughout their career. For each performance, the band drew material from an active list of a hundred or so songs.[103]

The 1969 live album Live/Dead did capture the band in-form, but commercial success did not come until Workingman's Dead and American Beauty, both released in 1970. These records largely featured the band's laid-back acoustic musicianship and more traditional song structures. With their rootsy, eclectic stylings, particularly evident on the latter two albums, the band pioneered the hybrid Americana genre.[104][105][106]

Instrumentation and musicianship

[edit]

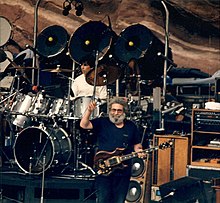

As the band and its sound matured over thirty years of touring, playing, and recording, each member's stylistic contribution became more defined, consistent, and identifiable. Garcia's lead lines were fluid, supple and spare, owing a great deal of their character to his experience playing Scruggs style banjo, an approach which often makes use of note syncopation, accenting, arpeggios, staccato chromatic runs, and the anticipation of the downbeat.[107]

Garcia had a distinctive sense of timing, often weaving in and out of the groove established by the rest of the band as if he were pushing the beat. His lead lines were also immensely influenced by jazz soloists: Garcia cited Miles Davis, Ornette Coleman, Bill Evans, Pat Martino, George Benson, Al Di Meola, Art Tatum, Duke Ellington, and Django Reinhardt as primary influences, and frequently utilized techniques common to country and blues music in songs that called back to those traditions.[108]

Garcia often switched scales in the midst of a solo depending upon the chord changes played underneath, though he nearly always finished phrases by landing on the chord-tones. Jerry most frequently played in the Mixolydian mode, though his solos and phrases often incorporated notes from the Dorian and major/minor pentatonic scales. Particularly in the late 1960s, Garcia occasionally incorporated melodic lines derived from Indian ragas into the band's extended, psychedelic improvisation, likely inspired by John Coltrane and other jazz artists' interest in the sitar music of Ravi Shankar.[109]

Lesh was originally a classically trained trumpet player with an extensive background in music theory, but did not tend to play traditional blues-based bass forms. He often played more melodic, symphonic and complex lines, often sounding like a second lead guitar. In contrast to most bassists in popular music, Lesh often avoids playing the root of a chord on the downbeat, instead withholding as a means to build tension. Lesh also rarely repeats the same bassline, even from performance to performance of the same song, and often plays off of or around the other instruments with a syncopated, staccato bounce that contributes to the Dead's unique rhythmic character.[110]

Weir, too, was not a traditional rhythm guitarist, but tended to play unique inversions at the upper end of the Dead's sound. Weir modeled his style of playing after jazz pianist McCoy Tyner and attempted to replicate the interplay between John Coltrane and Tyner in his support, and occasional subversion, of the harmonic structure of Garcia's voice leadings. This would often influence the direction the band's improvisation would take on a given night. Weir and Garcia's respective positions as rhythm and lead guitarist were not always strictly adhered to, as Weir would often incorporate short melodic phrases into his playing to support Garcia and occasionally took solos, often played with a slide. Weir's playing is characterized by a "spiky, staccato" sound.[111][112][113]

The band's two drummers, Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, developed a unique, complex interplay, balancing Kreutzmann's steady shuffle beat with Hart's interest in percussion styles outside the rock tradition. Kreuzmann has said, "I like to establish a feeling and then add radical or oblique juxtapositions to that feeling."[114] Hart incorporated an 11-count measure to his drumming, bringing a dimension to the band's sound that became an important part of its style. He had studied tabla drumming and incorporated rhythms and instruments from world music, and later electronic music, into the band's live performances.[115]

The Dead's live performances featured multiple types of improvisation derived from a vast array of musical traditions. Not unlike many rock bands of their time, the majority of the Dead's songs feature a designated section in which an instrumental break occurs over the chord changes. These sections typically feature solos by Garcia that often originate as variations on the song's melody, but go on to create dynamic phrases that resolve by returning to the chord-tones. Not unlike traditional improvisational jazz, they may occasionally feature several solos by multiple instruments within an undecided number of bars, such as a keyboardist, before returning to the melody. At the same time, Dead shows almost always feature a more collective, modal approach to improvisation that typically occurs during segues between songs before the band modulates to a new tonal center. Some of the Dead's more extended jam vehicles, such as "The Other One", "Dark Star", and "Playing in the Band" almost exclusively make use of modulation between modes to accompany simple two-chord progressions.[116]

Lyrical themes

[edit]Following the songwriting renaissance that defined the band's early 1970s period, as reflected in the albums Workingman's Dead and American Beauty, Robert Hunter, Jerry Garcia's primary lyrical partner, frequently made use of motifs common to American folklore including trains, guns, elements, traditional musical instruments, gambling, murder, animals, alcohol, descriptions of American geography, and religious symbolism to illustrate themes involving love and loss, life and death, beauty and horror, and chaos and order.[117] Following in the footsteps of several American musical traditions, these songs are often confessional and feature narration from the perspective of an antihero. Critic Robert Christgau described them as "American myths" that later gave way to "the old karma-go-round".[118]

An extremely common feature in both Robert Hunter's lyrics, as well as the band's visual iconography, is the presence of dualistic and opposing imagery illustrating the dynamic range of the human experience (Heaven and hell, law and crime, dark and light, etc.). Hunter and Garcia's earlier, more directly psychedelic-influenced compositions often make use of surreal imagery, nonsense, and whimsey reflective of traditions in English poetry.[119] In a retrospective, The New Yorker described Hunter's verses as "elliptical, by turns vivid and gnomic", which were often "hippie poetry about roses and bells and dew".[120] Grateful Dead biographer Dennis McNally has described Hunter's lyrics as creating "a non-literal hyper-Americana" weaving a psychedelic, kaleidoscopic tapestry in the hopes of elucidating America's national character. At least one of Hunter and Bob Weir's collaborations, "Jack Straw", was inspired by the work of John Steinbeck.[121]

Influence and legacy

[edit]Grateful Dead have been called a "symbol of the counterculture movement of the sixties". Beginning in the early 1990s, a new generation of bands became inspired by the Grateful Dead's improvisational ethos and marketing strategy, and began to incorporate elements of the Grateful Dead's live performances into their own shows. These include the nightly alteration of setlists, frequent improvisation, the blending of genres, and the allowance of taping, which would often contribute to the development of a dedicated fanbase. Bands associated with the expansion of the "jam scene" include Phish, The String Cheese Incident, Widespread Panic, Blues Traveler, moe., and the Disco Biscuits. Many of these groups began to look past the American roots music that the Grateful Dead drew inspiration from, and incorporated elements of progressive rock, hard rock, and electronica. At the same time, the Internet gained popularity and provided a medium for fans to discuss these bands and their performances and download MP3s. The Grateful Dead, as well as Phish, were one of the first bands to have a Usenet newsgroup.[122][123][124][125]

Merchandising and representation

[edit]Hal Kant was an entertainment industry attorney who specialized in representing musical groups. He spent 35 years as principal lawyer and general counsel for the Grateful Dead, a position in the group that was so strong that his business cards with the band identified his role as "Czar".[126]

Kant brought the band millions of dollars in revenue through his management of the band's intellectual property and merchandising rights. At Kant's recommendation, the group was one of the few rock 'n roll pioneers to retain ownership of their music masters and publishing rights.

In 2006, the Grateful Dead signed a ten-year licensing agreement with Rhino Entertainment to manage the band's business interests including the release of musical recordings, merchandising, and marketing. The band retained creative control and kept ownership of its music catalog.[127][128]

A Grateful Dead video game titled Grateful Dead Game – The Epic Tour[129] was released in April 2012 and was created by Curious Sense.[130]

In November 2022, the children's book The ABCs of The Grateful Dead was released.[131] Authorized by the group, it was written by Howie Abrams, illustrated by Michael "Kaves" McLeer, and published by Simon & Schuster.[132]

Sponsorship of 1992 Lithuanian Olympic basketball team

[edit]

After Lithuania gained its independence from the USSR, the country announced its withdrawal from the 1992 Olympics due to the lack of any money to sponsor participants.[133] But NBA star Šarūnas Marčiulionis, a native Lithuanian basketball star, wanted to help his native team to compete. His efforts resulted in a call from representatives of the Grateful Dead who set up a meeting with the band members.[134] The band agreed to fund transportation costs for the team (about $5,000) along with Grateful Dead designs for the team's jerseys and shorts. The Lithuanian basketball team won the bronze medal and the Lithuanian basketball/Grateful Dead T-shirts became part of pop culture, especially in Lithuania.[133][135] The incident was covered by the documentary The Other Dream Team.[136]

Live performances

[edit]

The Grateful Dead toured constantly throughout their career, playing more than 2,300 concerts.[137] They promoted a sense of community among their fans, who became known as "Deadheads", many of whom followed their tours for months or years on end. Around concert venues, an impromptu communal marketplace known as 'Shakedown Street' was created by Deadheads to serve as centers of activity where fans could buy and sell anything from grilled cheese sandwiches to home-made t-shirts and recordings of Grateful Dead concerts.[138]

In their early career, the band also dedicated their time and talents to their community, the Haight-Ashbury area of San Francisco, making available free food, lodging, music, and health care to all. It has been said that the band performed "more free concerts than any band in the history of music".[139]

With the exception of 1975, when the band was on hiatus and played only four concerts, Grateful Dead performed many concerts every year, from their formation in April 1965, until July 9, 1995.[140] Initially all their shows were in California, principally in the San Francisco Bay Area and in or near Los Angeles. They also performed, in 1965 and 1966, with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, as the house band for the Acid Tests.

In 1967, they toured nationally, including their first performance in New York City. They appeared at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, the Woodstock Festival in 1969 and the Festival Express train tour across Canada in 1970. They were scheduled to appear as the final act at the infamous Altamont Free Concert on December 6, 1969, after the Rolling Stones but withdrew after security concerns. "That's the way things went at Altamont—so badly that the Grateful Dead, prime organizers and movers of the festival, didn't even get to play", staff at Rolling Stone magazine wrote in a detailed narrative on the event.[141]

Their first UK performance was at the Hollywood Music Festival in 1970. Their largest concert audience came in 1973 when they played, along with the Allman Brothers Band and the Band, before an estimated 600,000 people at the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen.[142] They played to an estimated total of 25 million people, more than any other band, with audiences of up to 80,000 attending a single show. Many of these concerts were preserved in the band's tape vault, and several dozen have since been released on CD and as downloads. The Dead were known for the tremendous variation in their setlists from night to night—the list of songs documented to have been played by the band exceeds 500.[143] The band has released four concert videos under the name View from the Vault. In 1978, they played three nights at the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt.

In the 1990s, the Grateful Dead earned a total of $285 million in revenue from their concert tours, the second-highest during the 1990s, with the Rolling Stones earning the most.[144] This figure is representative of tour revenue through 1995, as touring stopped after the death of Jerry Garcia.[144]

In a 1991 PBS documentary, segment host Buck Henry attended an August 1991 concert at Shoreline Amphitheatre and gleaned some information from some band members about the Grateful Dead phenomenon and its success.[145] At the time, Jerry Garcia stated, "We didn't really invent the Grateful Dead, the crowd invented the Grateful Dead, you know what I mean? We were sort of standing in line, and uh, it's gone way past our expectations, way past, so it's, we've been going along with it to see what it's gonna do next."[145] Mickey Hart said, "This is one of the last places in America that you can really have this kind of fun, you know, considering the political climate and so forth."[145] Hart also stated that "the transformative power of the Grateful Dead is really the essence of it; it's what it can do to your consciousness. We're more into transportation than we are into music, per se, I mean, the business of the Grateful Dead is transportation."[145] One of the band's largest concerts took place just months before Garcia's death — at their outdoor show with Bob Dylan in Highgate, Vermont, on June 15, 1995. The crowd was estimated to be over 90,000; overnight camping was allowed and about a third of the audience got in without having purchased a ticket.[146][147][148]

Their numerous studio albums were generally collections of new songs that they had first played in concert. The band was also famous for its extended musical improvisations, having been described as having never played the same song the same way twice. Their concert sets often blended songs, one into the next, often for more than three songs at a time.

Concert sound systems

[edit]The Wall of Sound was a large sound system designed specifically for the band.[149][150] The band was never satisfied with the house system anywhere they played. After the Monterey Pop Festival, the band's crew 'borrowed' some of the other performers' sound equipment and used it to host some free shows in San Francisco.[151] In their early days, soundman Owsley "Bear" Stanley designed a public address (PA) and monitor system for them. Stanley was the Grateful Dead's soundman for many years; he was also one of the largest suppliers of LSD.[152]

Stanley's sound systems were delicate and finicky, and frequently brought shows to a halt with technical breakdowns. After Stanley went to jail for manufacturing LSD in 1970, the group briefly used house PAs, but found them to be even less reliable than those built by their former soundman. On February 2, 1970, the group contacted Bob Heil to use his system.[153] In 1971, the band purchased their first solid-state sound system from Alembic Studios. Because of this, Alembic would play an integral role in the research, development, and production of the Wall of Sound. The band also welcomed Dan Healy into the fold on a permanent basis that year. Healy would mix the Grateful Dead's live sound until 1993.

Following Jerry Garcia's death and the band's breakup in 1995, their current sound system was inherited by Dave Matthews Band. Dave Matthews Band debuted the sound system April 30, 1996, at the first show of their 1996 tour in Richmond, Virginia.

Tapes

[edit]Like several other bands at the time, the Grateful Dead allowed their fans to record their shows. For many years the tapers set up their microphones wherever they could, and the eventual forest of microphones became a problem for the sound crew. Eventually, this was solved by having a dedicated taping section located behind the soundboard, which required a special "tapers" ticket. The band allowed sharing of their shows, as long as no profits were made on the sale of the tapes.[154]

Of the approximately 2,350 shows the Grateful Dead played, almost 2,200 were taped, and most of these are available online.[155] The band began collecting and cataloging tapes early on and Dick Latvala was their keeper. "Dick's Picks" is named after Latvala. After his death in 1999, David Lemieux gradually took the post. Concert set lists from a subset of 1,590 Grateful Dead shows were used to perform a comparative analysis between how songs were played in concert and how they are listened online by Last.fm members.[156] In their book Marketing Lessons from the Grateful Dead: What Every Business Can Learn From the Most Iconic Band in History,[157] David Meerman Scott and Brian Halligan identify the taper section as a crucial contributor to increasing the Grateful Dead's fan base.

Iconography

[edit]Over the years, a number of iconic images have come to be associated with the Grateful Dead. Many of these images originated as artwork for concert posters or album covers.

- Skull and Roses

- The skull and roses design was composed by Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse, who added lettering and color, respectively, to a black and white drawing by Edmund Joseph Sullivan. Sullivan's drawing was an illustration for a 1913 edition of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. Earlier antecedents include the custom of exhibiting the relic skulls of Christian martyrs decorated with roses on their feast days. The rose is an attribute of Saint Valentine, who according to one legend, was martyred by decapitation. Accordingly, in Rome, at the church dedicated to him, the observance of his feast day included the display of his skull surrounded by roses.[158] Kelley and Mouse's design originally appeared on a poster for the September 16 and 17, 1966, Dead shows at the Avalon Ballroom.[159] Later, it was used as the cover for the album Grateful Dead (1971). The album is sometimes referred to as Skull and Roses.[160]

- Jester

- Another icon of the Dead is a skeleton dressed as a jester and holding a lute. This image was an airbrush painting, created by Stanley Mouse in 1972. It was originally used for the cover of The Grateful Dead Songbook.[161][162]

- "Dancing" Bears

- A series of stylized bears who appear to be dancing was drawn by Bob Thomas as part of the back cover for the album History of the Grateful Dead, Volume One (Bear's Choice) (1973). Thomas reported that he based the bears on a lead sort from an unknown font.[163] The bear is a reference to Owsley "Bear" Stanley, who recorded and produced the album. Bear himself wrote, "the bears on the album cover are not really 'dancing'. I don't know why people think they are; their positions are quite obviously those of a high-stepping march."[164]

- Steal Your Face Skull

- Perhaps the best-known Grateful Dead art icon is a red, white, and blue skull with a lightning bolt through it. The lightning bolt skull can be found on the cover of the album Steal Your Face (1976), and the image is sometimes known by that name. It was designed by Owsley Stanley and artist Bob Thomas, and was originally used as a logo to mark the band's equipment.[165]

- Dancing Terrapins

- The two dancing terrapins first appeared on the cover of the album Terrapin Station (1977). They were drawn by Kelley and Mouse, based on a drawing by Heinrich Kley. Since then these turtles have become one of the Grateful Dead's most recognizable logos.[166]

- Uncle Sam Skeleton

- The Uncle Sam skeleton was devised by Gary Gutierrez as part of the animation for The Grateful Dead Movie (1977).[167] The image combines the Grateful Dead skeleton motif with the character of Uncle Sam, a reference to the then-recently written song "U.S. Blues", which plays during the animation.

Deadheads

[edit]Fans and enthusiasts of the band are commonly referred to as Deadheads. While the origin of the term may be unclear, Dead Heads were made canon by the notice placed inside the Skull and Roses (1971) album by manager Jon McIntire:

DEAD FREAKS UNITE: Who are you? Where are you? How are you?

Send us your name and address and we'll keep you informed.

Dead Heads, P.O. Box 1065, San Rafael, California 94901.

As each show featured a new setlist and a great deal of improvisation, Deadheads would often follow the band from city to city, attending many shows on a given tour. Many Deadheads speak of being drawn to the culture due to the sense of community that the band's shows tended to foster. Though Deadheads came from a wide array of demographics, many attempted to reproduce the aesthetics and values of the 1960s counterculture and were often stigmatized in the media.[168] Because of the stereotyping of Deadheads as hippies, the band's shows became a common target for officials in the DEA and arrests at shows became common.[169]

As a group, the Deadheads were considered very mellow. "I'd rather work nine Grateful Dead concerts than one Oregon football game," Police Det. Rick Raynor said. "They don't get belligerent like they do at the games."[170] Despite this reputation, in the mid-1990s, as the band's popularity grew, there were a series of minor scuffles occurring at shows that peaked with a large scale riot at the Deer Creek Music Center near Indianapolis in July 1995. This gate crashing incident caused the band to cancel the following night's show.[171] Deadheads who appeared on the scene after the band's 1987 hit single "Touch of Grey", were often disparagingly referred to by older fans as "Touchheads". Beginning in the 1980s, a number of definable sects of Deadheads began to appear on the scene. These included the Wharf Rats, as well as the "spinners", named for whirling-style of dancing and their use of the band's music to facilitate mystical experiences.[172]

Deadheads, particularly those who collected tapes, were known for keeping close records of the band's setlists and for comparing various live versions of the band's songs, as reflected in publications such as the various editions of "Deadbase" and "The Deadhead's Taping Compendium". This practice continues into the 21st century on digital forums and websites such as the Internet Archive, which features live recordings of nearly every available Grateful Dead show and allows users to discuss and review the site's shows.

The band has a number of influential and celebrity fans, including politicians, businesspeople, journalists, and other musicians.

Donation of archives to UC Santa Cruz

[edit]On April 24, 2008, members Bob Weir and Mickey Hart, along with Nion McEvoy, CEO of Chronicle Books, UC Santa Cruz chancellor George Blumenthal, and UC Santa Cruz librarian Virginia Steel, held a press conference announcing UCSC's McHenry Library would be the permanent home of the Grateful Dead Archive, which includes a complete archival history from 1965 to the present. The archive includes correspondence, photographs, fliers, posters, and several other forms of memorabilia and records of the band. Also included are unreleased videos of interviews and TV appearances that will be installed for visitors to view, as well as stage backdrops and other props from the band's concerts.

Blumenthal stated at the event, "The Grateful Dead Archive represents one of the most significant popular cultural collections of the 20th century; UC Santa Cruz is honored to receive this invaluable gift. The Grateful Dead and UC Santa Cruz are both highly innovative institutions—born the same year—that continue to make a major, positive impact on the world." Guitarist Bob Weir stated "We looked around, and UC Santa Cruz seems the best possible home. If you ever wrote the Grateful Dead a letter, you'll probably find it there!"[173]

Professor of music Fredric Lieberman was the key contact between the band and the university, who let the university know about the search for a home for the archive, and who had collaborated with Mickey Hart on three books in the past, Planet Drum (1990), Drumming at the Edge of Magic (1991), and Spirit into Sound (2006).[174][175][176]

The first large-scale exhibition of materials from the Grateful Dead Archive was mounted at the New-York Historical Society in 2010.[177]

Awards

[edit]In 2004, Rolling Stone ranked the Grateful Dead No. 57 on their list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[178]

On February 10, 2007, the Grateful Dead received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. The award was accepted on behalf of the band by Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann.[179]

In 2011, a recording of the Grateful Dead's May 8, 1977, concert at Cornell University's Barton Hall was selected for induction into the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress.[180]

Twelve members of the Grateful Dead (the eleven official performing members plus Robert Hunter) were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994, and Bruce Hornsby was their presenter.[6]

In 2024 the band was named as one of the recipients of the Kennedy Center Honors. The three living core members (Weir, Hart and Kreutzmann) will receive the award.[22]

Members

[edit]

Lead guitarist Jerry Garcia was often viewed both by the public and the media as the leader or primary spokesperson for the Grateful Dead, but was reluctant to be perceived that way, especially since he and the other group members saw themselves as equal participants and contributors to their collective musical and creative output.[181][182] Garcia, a native of San Francisco, grew up in the Excelsior District. One of his main influences was bluegrass music, and he also performed—on banjo, one of his other great instrumental loves, along with the pedal steel guitar—in bluegrass bands, notably Old & In the Way with mandolinist David Grisman.

Ned Lagin, a young MIT student and friend of the band, guested with them many times from 1970 through 1975, providing a second keyboard as well as synthesizers. Upon graduating from MIT, he began touring with the band fulltime in 1974, performing sets of electronic music with Phil Lesh, occasionally with Garcia and Kreutzmann, during the band's intermission.[183] The "Ned and Phil" set became a regular fixture of that era, and was featured nearly every night during their Summer '74 and Europe '74 tours, as well as their five-night residency at the Winterland Ballroom during October 1974. Lagin is also featured in The Grateful Dead Movie. During 1974 and 1975, he would also occasionally play entire sets with the band, usually on Garcia's side of the stage, before ending his touring relationship with the band and focusing on his solo music projects, such as his album Seastones, which features several members of the Dead.[184]

Bruce Hornsby never officially joined the band full-time because of his other commitments, but he did play keyboards at most Dead shows between September 1990 and March 1992, and sat in with the band over 100 times in all between 1988 and 1995. He added several Dead songs to his own live shows[185] and Jerry Garcia referred to him as a "floating member" who could come and go as he pleased.[186][187][188]

Robert Hunter and John Perry Barlow were the band's primary lyricists, starting in 1967 and 1971, respectively, and continuing until the band's dissolution.[189][190] Hunter collaborated mostly with Garcia and Barlow mostly with Weir, though each wrote with other band members as well. Both are listed as official members at Dead.net, the band's website, alongside the performing members.[16] Barlow was the only member not inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Timeline

[edit]

Discography

[edit]- The Grateful Dead (1967)

- Anthem of the Sun (1968)

- Aoxomoxoa (1969)

- Live/Dead (1969)

- Workingman's Dead (1970)

- American Beauty (1970)

- Grateful Dead (Skull & Roses) (1971)

- Europe '72 (1972)

- History of the Grateful Dead, Volume One (Bear's Choice) (1973)

- Wake of the Flood (1973)

- From the Mars Hotel (1974)

- Blues for Allah (1975)

- Steal Your Face (1976)

- Terrapin Station (1977)

- Shakedown Street (1978)

- Go to Heaven (1980)

- Reckoning (1981)

- Dead Set (1981)

- In the Dark (1987)

- Dylan & the Dead (1989)

- Built to Last (1989)

- Without a Net (1990)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Meriwether, Nicholas G. (2012). Reading the Grateful Dead: A Critical Survey. Scarecrow Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-0-8108-8371-0.

- ^ Metzger, John (1999). "Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions". The Music Box. The Music Box, Inc. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- ^ "purveyors of freely improvised space music" – Blender Magazine, May 2003 Archived June 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "'Dark Star', both in its title and in its structure (designed to incorporate improvisational exploration), is the perfect example of the kind of 'space music' that the Dead are famous for. Oswald's titular pun 'Grayfolded' adds the concept of folding to the idea of space, and rightly so when considering the way he uses sampling to fold the Dead's musical evolution in on itself." – Islands of Order, Part 2, by Randolph Jordan, in Offscreen Journal Archived September 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, edited by Donato Totaro, Ph.D, film studies lecturer at Concordia University since 1990.

- ^ Santoro, Gene (2007). "Grateful Dead". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on March 22, 2007. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ^ a b "Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum – Grateful Dead detail". Inductees. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. Archived from the original (asp) on November 23, 2006. Retrieved January 16, 2007.

- ^ Kaye, Lenny (1970). "The Grateful Dead – Live/Dead". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ Garofalo, Reebee (1997). Rockin' Out: Popular Music in the USA. Allyn & Bacon. p. 219. ISBN 0205137032.

- ^ "The Grateful Dead Biography". rockhall.com. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ Sylvan, Robin (2002). Traces of the Spirit: The Religious Dimensions of Popular Music. NYU Press. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-0-8147-9809-6. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015.

- ^ Barnes, Luke (June 26, 2013). "UC Santa Cruz's Grateful Dead archive offers a reason to visit the campus this summer". santacruzsentinel.com. The Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 8, 2014. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ Meriwether, Nicholas G (August 5, 2023). "A map of where Grateful Dead lived, worked and played in SF". SFGATE. Archived from the original on August 5, 2023. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ Rolling Stone, p. 332

- ^ Garofalo, p. 218

- ^ Although he is identified as an official member on the band's website, Barlow (who frequently collaborated with Weir, Mydland and Welnick) was not inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. "The Grateful Dead". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ a b The Band Archived May 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Dead.net. Retrieved October 24, 2019

- ^ "Dead 50". Grateful Dead.

- ^ Kennedy, Mark (February 5, 2024). "The Grateful Dead make Billboard chart history despite disbanding in 1995". AP News. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ "The Greatest Artists of all Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011.

- ^ "The Grateful Dead: inducted in 1994". The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on April 16, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- ^ "New Entries to the National Recording Registry". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ a b "Grateful Dead, Francis Ford Coppola, Bonnie Raitt on 2024 Kennedy Center Honors list". Isabella Gomez.

- ^ Metzger, John. Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions album review Archived September 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Music Box, May 1999.

- ^ "Stu Goldstein as the emcee at The Tangent". Grateful Dead Archive Online. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- ^ Kreutzmann, Bill; Eisen, Benjy (2015). Deal: My Three Decades of Drumming, Dreams, and Drugs with the Grateful Dead. St. Martin's Press. page 33 ISBN 978-1-250-03379-6.

- ^ Lesh, Phil (September 3, 2007). Searching for the Sound: My Life with the Grateful Dead. Little, Brown. ISBN 9780316027816 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Clipped From Oakland Tribune". Oakland Tribune. September 13, 1965. p. 13 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The In Room, 1048 Old County Road, Belmont, CA". Jerry's Brokendown Palaces. January 24, 2013.

- ^ "Historic Photo - Old County Rd (Looking South)". City of Belmont.

- ^ "Magoo's Pizza Parlor – May 5, 1965 – Grateful Dead". Dead.net. May 5, 1965. Archived from the original on November 8, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ "Act I – It's Alive". Long Strange Trip. Season 1. Episode 1. June 2, 2017. 32:45 minutes in. Prime Video.

- ^ Lesh, Phil (2005). Searching for the Sound. New York, NY: Little, Brown, and Company. p. 62. ISBN 0316009989.

- ^ Weiner, Robert G. (1999). Perspectives on the Grateful Dead: Critical Writings. Greenwood Publishing. p. 145. ISBN 0-313-30569-2.

- ^ a b Troy, Sandy, Captain Trips: A Biography of Jerry Garcia (New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1994). DMT, p. 73; Acid King p. 70; Watts+ p. 85.

- ^ Boggs, Ralph Steele; Adams, Nicholson B (1932). Spanish folktales. F.S. Crofts. p. 113. OCLC 987857114.

- ^ "Big Nig's House – December 4, 1965 | Grateful Dead". Dead.net. March 30, 2007. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ Stanton, Scott (2003). The Tombstone Tourist. Simon & Schuster. p. 102. ISBN 0-7434-6330-7.

- ^ Herbst, Peter (1989). The Rolling Stone Interviews: 1967–1980. St. Martin's Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-312-03486-5.

- ^ "Get Shown the Light: Chapter 8 [1]". Daughter's Grimoire. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "In Conversation with Michael Kaler [1]". Daughter's Grimoire. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Live at Fillmore Auditorium on 1966-01-08". January 8, 1966. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011 – via Archive.org.

- ^ "50 Years Ago: Grateful Dead and Big Brother & the Holding Company Begin the Haight-Ashbury Era at the Trips Festival". Ultimate Classic Rock. January 31, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ^ Hirschfelder, Adam (January 14, 2016). "The Trips Festival explained". Experiments in Environment: The Halprin Workshops, 1966-1971.

- ^ Bromley, David G.; Shinn, Larry D. (1989), Krishna consciousness in the West, Bucknell University Press, p. 106, ISBN 978-0-8387-5144-2, archived from the original on June 10, 2016

- ^ Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A reader in new religious movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 213, ISBN 978-0-8264-6168-1, archived from the original on June 10, 2016

- ^ "Revisit the Grateful Dead's powerful gig at a protest against the Vietnam war, 1968 - Far Out Magazine". April 24, 2021.

- ^ "Drug Raid Nets 19 in French Quarter", The Times-Picayune, February 1, 1970

- ^ Planer, Lindsay. "Rolling Thunder: Review". AllMusic. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ "Pigpen Played His Final Show with the Grateful Dead Today in 1972". Relix. June 17, 2017. Retrieved December 6, 2017.

- ^ Scott, Dolgushkin, Nixon, "Deadbase X", New Hampshire, p. 23. ISBN 1-877657-21-2

- ^ McNally, Dennis, "A Long Strange Trip", New York 2002, p. 584. ISBN 0-7679-1186-5

- ^ a b "Grateful Dead Bio | Grateful Dead Career | MTV". Vh1.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ^ Pore-Lee-Dunn Productions. "The Grateful Dead". Classicbands.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ "Highlights Of The Grateful Dead Performing At Winterland In 1974". JamBase. March 26, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "'The Grateful Dead Movie' Was Released On This Day In 1977". L4LM. June 1, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ Spevak, Jeff. "Was '77 Grateful Dead show the best ever?". Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ Catalano, Jim. "40 years later, Grateful Dead's Barton Hall concert shines bright for the fans". Ithaca Journal. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ Cush, Andy (May 8, 2017). "Today Is "Grateful Dead Day", the 40th Anniversary of the Band's Legendary Cornell Show". Spin. Archived from the original on June 17, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- ^ Brooks, Dave (June 15, 2024). "George Strait Breaks Attendance Record With Largest Concert Ever Held in the U.S." Billboard. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Member Died Of Overdose, Coroner Rules". The New York Times. August 12, 1990. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009.

- ^ Carter, Andrew (August 26, 2023). "An In-Depth Look At The Long, Fruitful History Between Branford Marsalis & The Grateful Dead". L4LM. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Plays Final Show On This Date 25 Years Ago". JamBase. July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (December 9, 1995). "End of the Road for Grateful Dead; Without Garcia, Band Just Can't Keep Truckin'" Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (December 1, 2002). "Other Ones Reunite" Archived August 5, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (February 12, 2003). "Marin Icons Now the Dead", San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ "The Dead" Archived August 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Grateful Dead Family Discography. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ Budnick, Dean (September 18, 2013). "Dead Behind, Furthur Ahead" Archived July 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Relix. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (November 4, 2014). "Phil Lesh and Bob Weir Disband Furthur" Archived July 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ "Rhythm Devils Featuring Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann Announce Summer Tour" Archived July 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, KindWeb, May 27, 2010. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ "John Mayer Talks Grateful Dead Legacy, Fare Thee Well and Learning to Play 'A Universe of Great Songs'". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 14, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ^ Aniftos, Rania (September 23, 2022). "John Mayer Announces Final Dead & Company Tour". Billboard. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (February 2006). "RatDog's Return: Bob Weir and Life After Dead" Archived July 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Relix. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Greenhaus, Mike (February 14, 2014). "Bob Weir Ramps Up RatDog" Archived April 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, jambands.com. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Simon, Richard B. (June 2002). "Phil Lesh Goes There and Back Again" Archived July 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Relix. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (March 15, 2015). "Ex-Bassist for the Grateful Dead Strikes a Deal" Archived March 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times. Retrieved July 11, 2015.

- ^ Foster-Patton, Kathy (September 2006). "Micky Hart's Planet Drum Returns" Archived July 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, JamBase. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ^ "Interview: Mickey Hart" Archived July 12, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Digital Interviews, August 2000. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ^ Hutchinson, Nick (March 16, 2009). "Concert Review: Bill Kreutzmann Featuring Oteil Burbridge and Scott Murawski, Fox Theater, Boulder, CO" Archived July 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, jambands.com. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Powell, Austin (November 25, 2010). "Swampadelic: 7 Walkers Rise from the Dead" Archived July 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Austin Chronicle. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Bernstein, Scott (March 29, 2015). "Concert Review: Billy & the Kids, Capitol Theatre, Port Chester, NY" Archived July 9, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, JamBase. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ^ Selvin, Joel (June 3, 2008). "Donna Jean Godchaux Grateful to Sing Again" Archived July 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff (September 2, 2014). "Deadicated: Tom Constanten" Archived July 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Relix. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (October 23, 2014). "Martin Scorsese to Exec Produce Grateful Dead Doc". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 18, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Budnick, Dean (May 22, 2017). "Bringing the Grateful Dead to Life: Director Amir Bar-Lev on the Epic Long Strange Trip". Relix. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ^ Fear, David (January 24, 2017). "Sundance 2017: Grateful Dead Doc 'Long Strange Trip' Is Heartbreaking Tribute". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ "John Perry Barlow, Grateful Dead lyricist and advocate for an open Internet, dies at 70". Washington Post. February 8, 2018. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Hunter, Grateful Dead Lyricist, Dies at 78". The New York Times. September 24, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Gehr, Richard (October 25, 2024). "Phil Lesh, Grateful Dead Co-Founder and Bassist, Dead at 84". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 25, 2024.

- ^ a b Pareles, Jon (July 6, 2015). "Review: No Song Left Unsung, Grateful Dead Plays Its Last". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

When the Dead's music was working best, it always sounded like a healthy argument among old friends—one that could spark new ideas.

- ^ Sallo, Stewart (July 10, 2015). "Grateful Dead 'Fare Thee Well' Report Card" Archived July 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Huffington Post. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ Nelson, Jeff (January 19, 2015). "Grateful Dead 50th-Anniversary Reunion in the Works". People. Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ Halperin, Shirley (January 16, 2015). "Grateful Dead to Reunite, Jam with Trey Anastasio for Final Shows" Archived June 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Billboard. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (January 16, 2015). "Grateful Dead Reuniting for 50th-Anniversary Shows". CNN. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ Brandle, Lars (March 2, 2015). "Grateful Dead's 'Fare Thee Well' Tickets Offered for $116,000 on Secondary Market". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Bernstein, Lenny (March 6, 2015). "Op-Ed: Grateful Dead fans need a miracle, or big bucks, to see final Chicago shows". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ "Peter Shapiro: "We're Working on a Way to Bring the Show to Fans Who Aren't in Soldier Field" Archived July 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Relix, March 3, 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Coscarelli, Joe (July 2, 2015). "As Grateful Dead Exit, a Debate Will Not Fade Away" Archived April 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times. Retrieved July 6, 2015.

- ^ Grow, Kory (June 25, 2015). "Grateful Dead Announce Box Set Releases of Final Concerts" Archived June 27, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ Jackson, Blair (2000). Garcia: An American Life. Penguin. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-14-029199-5. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ Wolfe, Tom (1968). The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Farrar Straus & Giroux

- ^ Bjerklie, Steve. "What are They Worth?". Metroactive.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ Hegarty, Paul; Halliwell, Martin (2011), Beyond and Before: Progressive Rock Since the 1960s, New York: The Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 11, ISBN 978-0-8264-2332-0

- ^ a b The Grateful Dead: Playing in the Band, David Gans and Peter Simon, St Martin Press, 1985 p. 17

- ^ Willman, Chris (September 23, 2016), Bob Weir Grateful to Get Back in Touch With His Cowboy Side at Americana Fest, Billboard, archived from the original on September 26, 2016, retrieved October 24, 2016,

'In all likelihood, without the Grateful Dead and without Bob Weir, there would not be an Americana community', said Jed Hilly, executive director of the Americana Music Association...

- ^ McGee, Alan (July 2, 2009), "McGee on music: Why the Grateful Dead were Americana pioneers", The Guardian, archived from the original on October 25, 2016, retrieved October 24, 2016

- ^ Isaacs, Dave (November 1, 2011), The Grateful Dead & The Band – original Americana groups?, No Depression, archived from the original on October 31, 2016, retrieved October 30, 2016

- ^ "Defining bounce, drive, syncopation, timing, accent. bluegrass time - Discussion Forums - Banjo Hangout". www.banjohangout.org. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "The Grateful Dead's Jerry Garcia's 10 favourite guitarists". July 17, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Blair's Golden Road Blog: On Ravi Shankar and the Dead". Grateful Dead. December 14, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Collier, Rob (December 7, 2020). "Welcome to the Phil Zone: A Lesson in the Phil Lesh Style". Bass Musician Magazine, The Face of Bass. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "Grateful for Bob Weir". The New Yorker. April 25, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "Watch: Bob Weir Talks His Musical Role in the Grateful Dead". Relix Media. August 10, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Jarnow, Jesse (March 5, 2018). "Bob Weir and Phil Lesh Get Thrillingly Loose at New York Tour Openers". Rolling Stone. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "Bill Kreutzmann | Regal Tip". www.regaltip.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "Mickey Hart Biography". musicianguide.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Malvinni, David (October 21, 2010). "The Grateful Dead World: The Modal Basis of the Grateful Dead's Jams and Songs". The Grateful Dead World. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "Motif and theme index to The Annotated Grateful Dead Lyrics". artsites.ucsc.edu. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Christgau, Robert, Wake of the Flood (review), robertchristgau.com, retrieved October 30, 2016

- ^ "Nonsense & Whimsy in Robert Hunter's Lyrics". artsites.ucsc.edu. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Paumgarten, Nick (November 26, 2012). "Deadhead: The Afterlife". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 2, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Greatest Stories Ever Told - "Jack Straw"". Grateful Dead. May 30, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ https://www.pastemagazine.com/music/the-grateful-dead/the-everlasting-influence-of-jerry-garcia-and-the-grateful-dead

- ^ https://acousticguitar.com/acoustic-grateful-dead/

- ^ https://flyernews.com/ae/fare-thee-well-remembering-phil-lesh-of-the-grateful-dead/11/13/2024/

- ^ https://abc7news.com/post/remembering-phil-lesher-deadheads-descend-grateful-dead-house-san-francisco-following-death-bassist/15471552/

- ^ Barnes, Mike (October 22, 2008). "Grateful Dead lawyer Hal Kant dies" Archived April 5, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 24, 2008. (subscription required)

- ^ Light, Alan (July 10, 2006). "A Resurrection, of Sorts, for the Grateful Dead" Archived March 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2008

- ^ Liberatore, Paul (August 4, 2006). "Only the Memories Remain: Grateful Dead's Recordings Moved" Archived November 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved December 12, 2008

- ^ Browne, David (January 19, 2012). "Business Is Booming for the Grateful Dead". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ Riefe, Jordan (April 20, 2012). "Grateful Dead plan new "Epic Tour": in videogame". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- ^ "New Illustrated Children's Book Introduces Young Readers to the Grateful Dead". Jambands. October 25, 2022. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ Guzman, Richard (January 30, 2023). "Rock 'n' Read". Journal Gazette: A10.

- ^ a b "Salvation from the "dead": how Grateful Dead helped the Lithuanian basketball team get to the 1992 Olympics | HybridTechCar". hybridtechcar.com. May 10, 2018. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Nevius, C. W. (May 21, 1996). "Lithuanians Are Grateful to 'Dead' / Rock group came to rescue". SFGate. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Siegel, Alan (August 2, 2012). "Remembering The Joyous, Tie-Dyed All-Stars Of The 1992 Lithuanian Basketball Team". Deadspin. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ "Sundance: 'The Other Dream Team' and the Grateful Dead". EW.com. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Deadbase Online Search, ver 1.10

- ^ Bienenstock, David (January 28, 2015). "Deadheads Forever Changed the Way We Eat". Vice. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Garofalo, p. 219, quote in Garofalo, cited to Roxon, Lillian Roxon's Rock Encyclopedia.

- ^ Scott, Dolgushkin, Nixon, Deadbase X, ISBN 1-877657-21-2[page needed]

- ^ "Disaster at Altamont: Let It Bleed". Rolling Stone. January 21, 1970. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ McNally, Dennis, "A Long Strange Trip", New York 2002, pp. 455–58. ISBN 0-7679-1185-7

- ^ "deadlists home page". Deadlists.com. Archived from the original on August 31, 2004. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Waddell, Ray (July 2004). "The Dead Still Live for the Road". Billboard. Vol. 116, no. 27. p. 18. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. ISSN 0006-2510

- ^ a b c d Henry, Buck (October 1991). "Buck meets the Grateful Dead". Edge (PBS). Season 1, episode 1. Accessed September 9, 2018.

- ^ Hallenbeck, Brent (February 26, 2015). "VT security firm now ubiquitous". Burlington Free Press. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ Novack, Jay (Fall 1995). "June 15 - Franklin County Airport - Highgate, VT" (PDF). Unbroken Chain. October / November / December 1995 (53): 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ LIFE The Grateful Dead - The Long Strange Trip of the World's Greatest Jam Band. Essay by Patrick Leahy: Time Home Entertainment. August 16, 2019. ISBN 978-1547852055. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Pechner Productions- powered by SmugMug". Pechner.smugmug.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ "Alembic History – Long Version". Alembic.com. August 22, 2001. Archived from the original on July 12, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ "May–June 1967 Grateful Dead Itinerary Overview". lostlivedead.blogspot.com. January 1, 2010. Archived from the original on September 19, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ McNally, Dennis, "A Long Strange Trip", New York 2002, pp. 118–19. ISBN 0-7679-1185-7 and Brightman, Carol, "Sweet Chaos", New York 1998, pp. 100–04. ISBN 0-671-01117-0

- ^ Daley, Dan (December 2008). "The Night that Modern Live Sound Was Born: Bob Heil and the Grateful Dead". Performing Musician. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved May 7, 2011.

- ^ "Internet Archive: Grateful Dead". Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ Ratliff, Ben (April 10, 2009). "Bring Out Your Dead". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2016.

- ^ Rodriguez, Marko; Gintautas, Vadas; Pepe, Alberto (January 2009). "A Grateful Dead Analysis: The Relationship Between Concert and Listening Behavior". First Monday. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010.

- ^ Scott, David Meerman; Hlligan, Brian (August 2, 2010). Marketing Lessons from the Grateful Dead: What Every Business Can Learn From the Most Iconic Band in History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-90052-9.

- ^ Rome: A Holiday Magazine Travel Guide. New York: Random House. 1960.

- ^ du Lac, J. Freedom (April 12, 2009). "The Dead's Look Is Born". The Washington Post. p. E-8.

- ^ "Grateful Dead (Skull and Roses) on". Deaddisc.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ ""Grateful Dead Songbook (Front)" on". Dead.net. November 5, 1972. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ ""Mouse Grateful Dead Songbook Jester" on". Rockpopgallery.com. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ "Back cover of History of the Grateful Dead Vol. 1 (Bear's Choice) on". Dead.net. July 6, 1973. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ "Creation of the dancing bear, as told by Owsley "Bear" Stanley". Thebear.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ "Creation of the lightning bolt skull, as told by Owsley "Bear" Stanley". Thebear.org. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ Huber, Chris (March 3, 2021). "The History and Meaning of the Grateful Dead Terrapin Turtles". Extra Chill.

- ^ McNally, p. 499

- ^ "Deadheads – Subcultures and Sociology". Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ^ "DEA targeting 'Deadheads' at concerts". Baltimore Sun. March 28, 1994.

- ^ Brock, Ted (June 26, 1990). "Morning briefing: In Oregon, they're grateful for all the extra cash they get". Los Angeles Times. p. C2.

- ^ "Deadheads Crash Fence During Grateful Dead Concert At Deer Creek On This Date 25 Years Ago". JamBase. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Apichella, Mike. "Deadheads, Spinners and Spirituality". Splice Today. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Archive News". University of California, Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on August 25, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2011.

- ^ Rappaport, Scott (April 24, 2008). "Grateful Dead Donates Archives to UC Santa Cruz". UC Santa Cruz News and Events. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010.

- ^ Green, Joshua. "Management Secrets of the Grateful Dead" The Atlantic, March 2010

- ^ "Goodreads: Fredric Lieberman". Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ "Grateful Dead: Now Playing at the New-York Historical Society". New-York Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Haynes, Warren (December 3, 2010). "100 Greatest Artists of All Time: Grateful Dead". Rolling Stone issue 946. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ Zeidler, Sue (February 11, 2007). "Death Permeates Grammy Lifetime Achievement Awards", Reuters, via the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ^ "Complete National Recording Registry Listing – National Recording Preservation Board | Programs". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on May 20, 2017. Retrieved May 26, 2017.

- ^ "The way it works is it doesn't depend on a leader, and I'm not the leader of the Grateful Dead or anything like that; there isn't any fuckin' leader." Jerry Garcia interview, Rolling Stone, 1972