Will Clark

| Will Clark | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

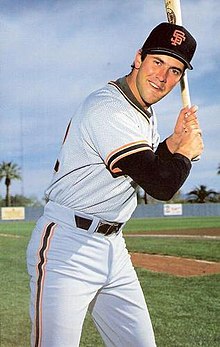

Clark with the Giants in 1986 | |||||||||||||||

| First baseman | |||||||||||||||

| Born: March 13, 1964 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. | |||||||||||||||

Batted: Left Threw: Left | |||||||||||||||

| MLB debut | |||||||||||||||

| April 8, 1986, for the San Francisco Giants | |||||||||||||||

| Last MLB appearance | |||||||||||||||

| October 1, 2000, for the St. Louis Cardinals | |||||||||||||||

| MLB statistics | |||||||||||||||

| Batting average | .303 | ||||||||||||||

| Hits | 2,176 | ||||||||||||||

| Home runs | 284 | ||||||||||||||

| Runs batted in | 1,205 | ||||||||||||||

| Teams | |||||||||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Medals

| |||||||||||||||

William Nuschler Clark Jr. (born March 13, 1964) is an American professional baseball first baseman who played in Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1986 through 2000. He played for the San Francisco Giants, Texas Rangers, Baltimore Orioles, and St. Louis Cardinals. Clark was known by the nickname of "Will the Thrill." The nickname has often been truncated to simply, "the Thrill."[1][2]

Clark played college baseball for the Mississippi State Bulldogs, where he won the Golden Spikes Award, and at the 1984 Summer Olympics before playing in the major leagues. Clark was a six-time MLB All-Star, a two-time Silver Slugger Award winner, a Gold Glove Award winner, and the winner of the National League Championship Series Most Valuable Player Award in 1989.

Clark has been inducted into the National College Baseball Hall of Fame, Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame, Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame, and Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame. His uniform number, 22, was retired by the Giants during the 2022 season. Clark continues to be active in baseball, serving as a Special Assistant in the Giants' front office.[3]

Early life

[edit]Clark was born and raised primarily in New Orleans, Louisiana.[1] He graduated from Jesuit High School.[4] He grew up a Kansas City Royals fan and was drafted by the Royals in the 4th round of the 1982 draft but chose not to sign.[5][6]

College career

[edit]Clark attended Mississippi State University to play college baseball for the Mississippi State Bulldogs. In 1983, he played collegiate summer baseball for the Cotuit Kettleers of the Cape Cod Baseball League (CCBL). A league all-star, Clark batted .367 and was inducted into the CCBL Hall of Fame in 2004.[7] Clark played for the United States national baseball team at the 1984 Summer Olympics. During the five-game Olympic tournament, Clark led the team in batting average (.429), hits (9), runs batted in (8) and tied for the team lead in home runs (3).[8]

In 1985, The Sporting News named Clark an All-American and he later won the Golden Spikes Award from USA Baseball as the best amateur baseball player in the country. A teammate of Rafael Palmeiro, the two were known as "Thunder and Lightning."[9] Clark and Palmeiro were known to dislike each other, dating back to their time at Mississippi State.[10]

Professional career

[edit]Draft and minor leagues

[edit]Clark was drafted with the second overall pick in the 1985 Major League Baseball draft by the San Francisco Giants.[11]

San Francisco Giants (1986–1993)

[edit]In his first major league at-bat on April 8, 1986, on his first swing, Clark hit a home run off Nolan Ryan.[11] A few days later, Clark also homered in his first home game at Candlestick Park. An elbow injury cost Clark 47 games in his rookie season.[11] Clark finished the year with a .287 batting average and placed fifth in National League Rookie of the Year voting.

In his first full season in 1987, Clark had a .308 batting average. Clark was voted the starting first baseman for the NL All-Star team every season from 1988 through 1992. In 1988, Clark was the first Giants' player to drive in 90 or more runs in consecutive seasons since Bobby Murcer from 1975-1976.

In 1989, Clark batted .333 (losing the batting title to Tony Gwynn on the final day of the season) with 111 runs batted in (RBIs). Clark finished second in the NL Most Valuable Player voting to Giants teammate Kevin Mitchell. In 1989, Clark and the Giants defeated the Chicago Cubs in the National League Championship Series (NLCS). In Game 1, Clark had already hit a solo home run. Prior to a subsequent at-bat, Cubs' catcher Rick Wrona went to the mound to discuss with Greg Maddux how to pitch to Clark. From the on-deck circle, Clark watched the conversation and read Greg Maddux's lips saying "fastball high, inside." The first pitch was a fastball high and inside which Clark sent into the street beyond right field for a grand slam. Afterwards, pitchers began to cover their mouths with their gloves when having conversations on the pitcher's mound.[12] (The Chicago Tribune's front page the next day paid tribute to his performance with a headline of "Clark's night on Addison", referring to the street outside Wrigley Field where the home runs landed.[13])

In Game 5 of the series, Clark faced Cubs closer Mitch Williams with the score 1–1 in the bottom of the eighth inning. Clark singled to center field to drive in two runs, breaking the tie, eventually sending the Giants to the World Series. Clark's efforts, which included a .650 batting average and two home runs, resulted in him being named NLCS MVP. The Giants went on to face the Oakland Athletics in the 1989 World Series, but were swept. In the only World Series appearance of his career, Clark failed to contribute significantly at the plate, finishing with no runs batted in and a .250 batting average while battling tonsillitis.[14]

Clark had become a very durable player since his rookie year injury, setting a San Francisco record with 320 consecutive games played from September 1987 through August 1989.[11] In January 1990, he signed a four-year, $15 million contract with the Giants, which at the time made him the highest-paid player in the majors.[15] However, a string of injuries reduced his playing time in the early 1990s and diminished his production. Clark drove in just 73 runs in 1992, the lowest total since his rookie year.[6]

Texas Rangers (1994–1998)

[edit]The Texas Rangers signed Clark to replace his former Mississippi State teammate, Rafael Palmeiro, at first base. Clark made the American League All-Star team in 1994[6] and finished the season with a .329 batting average, the second-highest of his career. He maintained a high level of offensive production throughout his tenure with Texas, finishing below .300 only in 1996. Injuries limited his playing time to 123, 117 and 110 games from 1995 through 1997, but Clark led the Rangers to American League West Division titles in 1996 and 1998. Clark struggled offensively in both the 1996 and 1998 postseasons, though he put together his most productive regular season in seven years in 1998 (.305, 23 HRs, 41 2Bs, 102 RBIs). Following the 1998 season, the Rangers re-signed Rafael Palmeiro, effectively ending Clark's days with the team.

Baltimore Orioles and St. Louis Cardinals (1999–2000)

[edit]Clark signed a two-year deal with the Orioles before the 1999 season, again replacing Palmeiro, who had left Baltimore to return to Texas. Part of the reason Clark chose Baltimore was to be near Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, since Clark's son, Trey, has autism.[16] Clark spent nearly two years with Baltimore but was plagued by injuries. On June 15, Clark got his 2000th hit versus the Kansas City Royals.

At the MLB trade deadline in 2000, the Orioles traded Clark to the St. Louis Cardinals for José León. He was acquired in part to play in place of the injured Mark McGwire.[17] Clark batted .345 while hitting 12 home runs and driving in 42 runs in 51 games. Clark helped the Cardinals defeat the Atlanta Braves in the NLDS with four runs batted in during the series. In the NLCS, the Cardinals faced the New York Mets. Clark batted .412 in the series but the Mets won the series and the National League pennant. Despite being revitalized during his time with the Cardinals, he decided to retire at the end of the season, largely due to familial obligations.[16] Clark batted .319 during his final season and went 1 for 3 in his final game on October 16, 2000.

Legacy

[edit]

Clark was inducted into the College Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006. He was inducted into the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame in June 2004,[18] the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame on April 26, 2007,[19][20] and the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame on August 1, 2008.[21] Clark's final statistics were 284 home runs, 1,205 RBI, a .303 batting average, and a .881 OPS.[22] In 2006 Hall of Fame balloting, Clark received 23 votes, 4.4% of the total, which withdrew him from consideration from future ballots, as he did not receive the required 5% threshold to stay on.[23]

Will holds the record for most home runs against Hall of Fame Pitcher Nolan Ryan with 6.[24]

It was announced on August 11, 2019, that the Giants would retire Clark's #22 during the 2020 season.[25] However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic the retirement ceremony was postponed to 2022.[26] Clark's number was ceremoniously retired on July 30, 2022.

Accomplishments and Honors

[edit]| Title | Times | Dates |

|---|---|---|

| National League champion | 1 | 1989 |

| Category | Times | Seasons |

|---|---|---|

| National League RBI leader | 1 | 1988[6] |

| Plate appearance | 1 | 1988[6] |

| Base on Balls (Walks) | 1 | 1988[6] |

| Intentional base on balls (Intentional Walks) | 1 | 1988[6] |

| Runs | 1 | 1989[6] |

| Slugging Percentage | 1 | 1991[6] |

| Total bases | 1 | 1991[6] |

Personal life

[edit]Clark is married to his wife, Lisa White Clark, whom he wed in 1994.[41][42] Their son Trey was born in 1996.[43] In 1998, at age two, Trey was diagnosed with autism. Will and Lisa also have a daughter, Ella.[16] Clark is a spokesman for Autism Speaks and Anova.[44] In 1999, Clark's wife Lisa had open heart surgery to address a hole that had been undiagnosed since birth.[43]

See also

[edit]- List of Major League Baseball annual putouts leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career assists as a first baseman leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career games played as a first baseman leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career OPS leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players with a home run in their first major league at bat

References

[edit]- ^ a b Swift, E.M. (May 28, 1990). "Will Power". Sports Illustrated. New York City: Time. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ "William Nuschler 'Will' Clark, Jr. - 1B". BaseballEvolution.com. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ "Front Office Roster". MLB. San Francisco Giants. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- ^ Cuicchi, Richard. "Will Clark". Society for American Baseball Research. Archived from the original on April 16, 2024. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ Clark, Will (May 1, 2018). "Hi, I'm Will Clark, here to answer your questions @ 2:30 PM PT - AMA!". Reddit.com/r/SFGiants (Interview). Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Will Clark". Baseball Reference. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ "Ten Legends to be Inducted into Cape Cod Baseball League Hall of Fame". Cape Cod Baseball League. June 13, 2004. Archived from the original on December 17, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^ Cuicchi, Richard (March 19, 2018). "Oh, What a Thrill! Will Clark: Career Overview (Part 2)". Crescent City Sports.

- ^ Norwood, Andrew (April 29, 2015). "SEC Storied: Thunder & Lightning to Premiere Monday". M&W Nation.

- ^ Chass, Murray (March 9, 1994). "Baseball; Thoughts Deep in the Heart of Texas". The New York Times. p. B13. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Will Clark". BaseballBiography.com. Retrieved September 26, 2024.

- ^ Stark, Jayson (August 21, 2013). "Talk to the glove!". ESPN. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1989, page A1

- ^ "Raspy, Feverish, Will Clark Skips Batting Practice". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. October 16, 1989.

- ^ "Will Clark Package Zooms to $15 Million". The New York Times. Associated Press. January 23, 1990. p. B9. Retrieved September 27, 2024. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Courtney, Lloyd (May 17, 2015). "Where are they now: Will Clark focuses on family". The Times. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ "Orioles trade Clark, Surhoff to NL contenders". ESPN. Associated Press. July 31, 2000. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Will Clark". Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Inductees (2007)". Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on April 8, 2011.

- ^ FitzGerald, Tom (April 27, 2007). "New inductees remember / Rice, ex-Giant Clark among those recalling their finest hours". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Rubenstein, Michael (July 11, 2008). "Induction Weekend Opens Friday; Tickets Available". Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ "Will Clark". The Baseball Cube. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ Haft, Chris (November 29, 2016). "Will in-depth numbers support Clark's cause?". MLB. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Nolan Ryan Career Home Runs Allowed". Baseball Reference. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Giants to retire Will Clark's No. 22 next year". ESPN. August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ Pavlovic, Alex (February 20, 2021). "Giants likely to push Will Clark ceremony back to 2022". NBCSportsBayArea.com. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Baseball Digest Player of the Year Award". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Will Clark". Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Golden Spikes Award Winners". USA Baseball. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Hall of Fame Distinguished Members" (PDF). Louisiana High School Athletic Association. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Will Clark". Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Player of the Month". MLB. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Player of the Week". MLB. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "William 'Will' Clark". Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "The Mississippi State Sports Hall of Fame". Mississippi State University Athletics. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "2006 College Baseball Hall of Fame Inductees". MLB. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "League Championship Most Valuable Player Award". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Will the Thrill's 22 immortalized at Oracle Park". MLB. July 30, 2022. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Gold Glove Winner". Rawlings. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Silver Slugger". MLB. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Who is Will Clark Wife Lisa Clark? Meet the Former American professional Baseball Player Family". August 2022.

- ^ "Lisa White Clark (@lisawhiteclark) • Instagram photos and videos". Instagram.com. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Dark Moment For Clark Has Softened His Glare". Sun Sentinel. February 26, 1999. Retrieved August 2, 2022. (subscription required)

- ^ O'Carroll, Bailey (July 31, 2022). "Giants legend Will Clark says his biggest life challenge happened off the field, as a dad". KTVU. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Will Clark at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- 1964 births

- Living people

- Arizona Diamondbacks executives

- Baltimore Orioles players

- Baseball players at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- National College Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Gold Glove Award winners

- Golden Spikes Award winners

- Jesuit High School (New Orleans) alumni

- Major League Baseball first basemen

- Baseball players from Louisiana

- Mississippi State Bulldogs baseball players

- St. Louis Cardinals players

- San Francisco Giants executives

- San Francisco Giants players

- Texas Rangers players

- National League Championship Series MVPs

- Silver Slugger Award winners

- Medalists at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- Olympic silver medalists for the United States in baseball

- All-American college baseball players

- Cotuit Kettleers players

- Southeastern Conference Athlete of the Year winners